A few days ago, the company VOTIX released its much-anticipated white paper addressing an issue that is central to their core business: the role that software will play in the inevitable integration of crewed and uncrewed aviation in the National Airspace System (NAS).

The FAA's proposed Parts 108 and 146 represent the most ambitious re‑architecture of uncrewed aviation since the introduction of Part 107 in the summer of 2016. In Enterprise Drone Systems and the New FAA Paradigm, VOTIX argues that these rules do more than modernize regulatory oversight; they redefine the very nature of aviation authority. The white paper’s central premise is bold: Under the new framework, software becomes a critical support to the operator, and systemic reliability replaces human reliability as the foundation of safety.

Today, we would like to analyze the core argument of the document, evaluate its interpretation of the federal agency’s intent, and brief on its conclusions about the future of unmanned aviation. For that, Commercial UAV News reached out to VOTIX founder and CEO Edwin Sanchez for exclusive comments about the document his company released.

“After the release of the NPRM of Part 108, me and my team felt that it is imperative that we write something explaining to the general public the stark differences between the approach of the established Part 107 and the proposed Part 108 in everything related to software, especially in systems that focus on command-and-control of drone operations at scale,” Sanchez said. “We prefer the definition of drone orchestration and automation platforms because it aligns better with the long-term vision of the FAA. But regardless of how operators understand the role of software in the new Part 108 reality, this white paper is for them.”

From Human-Centric to System-Centric Aviation

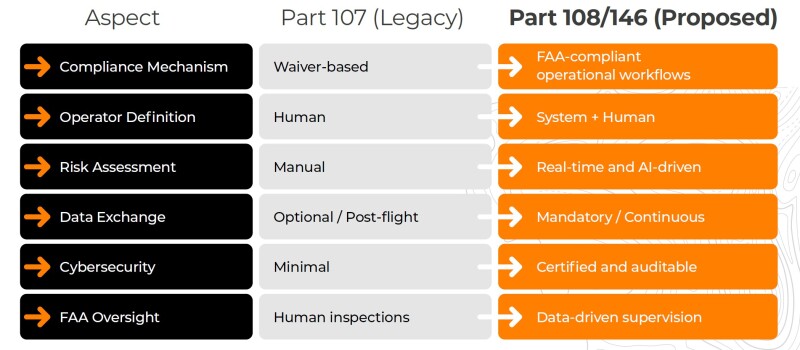

The white paper opens by framing Part 107 as a transitional regime. When introduced, Part 107 democratized commercial drone operations, but it also placed the human pilot at the center of compliance. Every element of safety, risk assessment, airspace checks, go/no‑go decisions, and post‑flight reporting depended on human interpretation. As operations scaled and BVLOS ambitions grew, this model strained under its own weight. Waivers proliferated, oversight became inconsistent, and manual processes created latency and error.

VOTIX argues that the FAA’s shift toward Parts 108 and 146 is a response to this structural limitation. The agency is not merely updating rules; it is redesigning the architecture of airspace governance for the next half‑century. The new paradigm replaces human‑only accountability with systemic reliability, defined as safety demonstrated through consistent, auditable, workflow‑driven system behavior.

In this framing, the FAA is acknowledging a reality: Unmmanned aviation has matured into critical infrastructure. Drones now support public safety, industrial inspection, logistics, and emergency response. As their role expands, the regulatory model must evolve from human‑centered oversight to software‑governed assurance.

Part 108: Redefining the Operator

The most consequential claim of this important document is that Part 108 fundamentally redefines what it means to ‘operate’ an unmanned aircraft. Under the proposed rule, the operator is no longer exclusively a human being. Instead, the operator becomes a system, where humans supervise and authorize, but software executes the operational logic.

VOTIX identifies five principles at the core of this new operator framework:

- Systemic Reliability: Safety emerges from system design and continuous verification.

- Operational Assurance: Every flight must be auditable through FAA‑compliant workflows.

- Real-Time Decision Logic: Software must continuously evaluate airworthiness and external conditions.

- Automation as Accountability: Automated decisions must align with FAA‑defined thresholds.

- Cyber‑Resilient Operation: Systems must be protected against tampering and interference.

In this model, the pilot becomes a supervisor rather than the primary executor of safety functions. The operator software performs pre‑flight validation, real‑time risk assessment, in‑flight adjustments, and post‑flight evidence generation. Certification shifts from evaluating human skill to evaluating system behavior.

The white paper interprets this as a philosophical shift: trust is earned through data, not credentials. Compliance becomes continuous, not conditional.

Part 146: The Data Backbone of Automated Aviation

If Part 108 defines who acts, Part 146 defines what informs them. The white paper describes Automated Data Service Providers (ADSPs) as the "intelligence fabric" of the new airspace. These software entities ingest, validate, and distribute operationally relevant data, weather, micro‑weather, NOTAMs, geofencing, population density, electromagnetic interference, and more.

The relationship between Operator Software (Part 108) and ADSPs (Part 146) is symbiotic. Operator Software relies on ADSPs for real‑time context; ADSPs rely on operators to execute decisions based on that context. Together, they create a dynamic, machine‑speed compliance ecosystem.

The white paper emphasizes that this architecture eliminates the bottlenecks inherent in operations that rely in the granting of a waiver by the FAA. Instead of requesting permission for each BVLOS mission, operators demonstrate systemic compliance through certified behaviors. This enables the FAA’s stated goal: thousands of simultaneous BVLOS flights across industries and geographies, without overwhelming human oversight.

Enterprise Drone Platforms as the New Compliance Engine

A major portion of the white paper is dedicated to the role of Enterprise Drone Platforms (EDPs), which are positioned as the practical embodiment of the FAA’s new regulatory philosophy. EDPs integrate command‑and‑control (C2), compliance workflows, ADSP data streams, cybersecurity layers, and AI‑driven analytics into a unified operational system.

The paper argues that under Parts 108 and 146, EDPs become the operator’s primary control and compliance mechanism. They verify weather and airspace conditions, execute automated risk assessments, adjust flight paths, log telemetry, and generate digital evidence trails. In essence, they translate regulatory intent into operational code.

“The document uses VOTIX as a case study, highlighting its integrations with micro‑weather providers, UTM networks, ADS‑B systems, and cybersecurity frameworks.” Sanchez concluded. “While I understand that its promotional in tone, the VOTIX example illustrates the broader point: compliance under the new rules requires deeply integrated, certifiable software systems.”

Cybersecurity and Data Exchange as Safety Requirements

The white paper devotes significant attention to cybersecurity, arguing that in a software‑dependent airspace, digital vulnerabilities become safety hazards. Under Part 108, cybersecurity is not an IT concern but a condition of operational worthiness.

The paper outlines a ten‑layer cybersecurity model, encryption, access control, firmware validation, intrusion detection, data immutability, and more, positioning these controls as essential to maintaining trust in automated operations. It also highlights the FAA’s expectation of near‑zero‑latency data exchange, with sub‑second round‑trip times required for real‑time risk assessment.

The implication is clear: compliance is no longer about checklists; it is about continuous, secure, high‑frequency data flow. This fits nicely into the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) effort to push In-Time Aviation Safety Management Systems (IASMS) even though the document does not mention it specifically.

Industry Evolution: Compliance Race, Service Mesh, and Autonomy

The white paper concludes with a forward‑looking analysis of how the industry will evolve under Parts 108 and 146. It predicts three phases:

1. Near Future (1–3 years): A ‘compliance race’ where operators with enterprise‑grade software surge ahead, while manual, pilot‑centric programs stagnate.

2. Mid‑Future (3–7 years): Emergence of a ‘service mesh airspace’ where ADSPs and EDPs coordinate large‑scale autonomous operations across cities and industries.

3. Far Future (7–15 years): Fully autonomous aviation, with humans providing strategic oversight while certified AI agents execute operational logic.

The paper argues that this evolution positions the United States as a global leader in autonomous aviation, with software‑centric compliance becoming a competitive advantage.

Conclusion: A New Digital Airspace Order

VOTIX’s white paper presents a compelling, if ambitious, vision of the FAA’s regulatory future. Its core argument, that software becomes the operator and systemic reliability becomes the foundation of safety, is consistent with the direction of recent FAA rulemaking and industry trends. The document’s strength lies in articulating how Parts 108 and 146 interlock to create a scalable, data‑driven, automated airspace.

Its conclusions are clear:

- Compliance becomes continuous and software‑driven.

- Operators must adopt enterprise‑grade platforms to remain viable.

- Cybersecurity and data exchange have become safety imperatives.

- The FAA is building not a drone system, but the foundation for autonomous aviation both crewed and uncrewed.

Whether one agrees with the pace or scope of this transformation, the white paper captures a pivotal moment in aviation history, one where the pilot’s seat is increasingly occupied by code, and where the future of airspace governance is written in software.

Comments