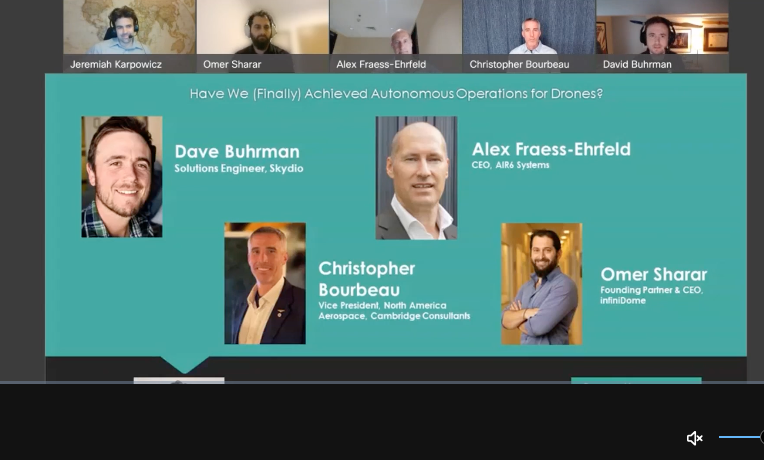

Our recent Have We (Finally) Achieved Autonomous Operations for Drones? webinar explored numerous questions and issues related to distinct technical, regulatory and operational elements of flying drones in an autonomous manner. Dave Buhrman from Skydio, Alex Fraess-Ehrfeld from AIR6 Systems, Christopher Bourbeau from Cambridge Consultants and Omer Sharar from infiniDome participated in a discussion that explored standard definitions of autonomy, the security ramifications around using drones in this manner, how such operations can impact scale, and much more.

In fact, there was so much to get to during the webinar that we weren’t able to address many of the excellent questions that came in from the live audience. We took the best of those questions and threw them out to the participants to facilitate the continuation of this discussion with each of them.

Click here to watch or listen to the webinar.

In your opinion when, does it become autonomous compared to highly automated and managing non-conforming uncrewed aircraft? For example, we can already run BVLOS multiple airframes at the same time. Is it autonomous when we remove the pilot managing the non-confirming or when we get to a certain number (50 uncrewed monitored by one pilot)?

Alex Fraess-Ehrfeld: Real autonomy for me is end-to-end autonomy. So the fact that an operation is BVLOS or done in a swarm constellation does not necessarily mean there is autonomy. Nevertheless, we have to start somewhere and replacing navigation skill and complex manoeuvres through part-autonomy or offering comfort in a way that the operator can concentrate on monitoring the airspace is already a very good start.

Agree or disagree: until the FAA can open up BVLOS and Type Certification to autonomous drone suppliers and service providers (as well as end user organizations) then adoption will continue to remain limited compared to the potential total available market which is much larger.

Omer Sharar: Completely agree. Until FAA ARC BVLOS committee completes writing the rules on how to fly BVLOS waiver-less, the market will not get close at fulfilling its potential.

Alex Fraess-Ehrfeld: Totally agree. Real autonomy or end-to-end autonomy is only possible with BVLOS certification. I am thinking of power lines, pipelines or offshore wind farm inspections, for instance. For the latter we are currently working on a fully autonomous solution in the context of our Dr-SUIT project which stands for “Drone Swarm for Unmanned Inspection of Wind Turbines”. BVLOS and Type Certification would overcome current inefficiencies with drones at corridor mapping and inspections when such corridors have to be split-up in VLOS segments, while our technology is ready for autonomous data flights over distances of 10 – 20 km, remotely monitored from a distant control centre.

We did not discuss indoor uses for autonomous drone use. Are you working on systems to support indoor inspections which lack GPS guidance?

Dave Buhrman: Good question! This is an often-overlooked challenge of GPS based drones. They cannot fly inside, and if they do, require heavy reliance on manual skill. Because Skydio operates using visual navigation, our drones operate the exact same way inside as they do outside. This of course opens up myriad different use cases for indoor inspection from perimeter security to inventory management.

Redundancy in navigation will always be key, and GPS will likely be an integral part of how drones operate. Skydio however only uses GPS as a backup to our primary source of navigation.

Alex Fraess-Ehrfeld: GPS-denied operations are very essential for AIR6 Systems, indoors or outdoors in confined spaces. The future will bring certainly a mix of indoor / outdoor applications for drones, although the outdoor market will prevail. The short answer is yes, we are working on an indoor inspections and monitoring drone, as part of a specific customer requirement and mandate. End-to-end autonomy plays here a key role – from start to land to self maintenance.

What happens when an AI drone fails in the air and crashes due to unforeseen circumstance (birds, wind bursts, precipitation. etc)? What risk aversion needs to be taken into account for these situations?

Dave Buhrman: Risk in aviation (or any activity) is never zero. In aerospace, we do our best to mitigate that risk to as close to zero as possible. The FAA, for example, holds extremely high standards for flight carrying passengers because the severity of a malfunction is extremely high, so the FAA strives to reduce the likelihood of those malfunctions. For small drones, the likelihood of a malfunction is much higher, but the severity is much lower. Because of this, the FAA has adjusted their mindset when it comes to certification. It is unreasonable to expect that a small drone manufacturer would be subjected to the same rigor as Boeing and their 737s.

With that said, we should hold ourselves to a higher standard for drones operating autonomously. If there is not an operator in the field to determine weather conditions, environmental factors, or other risks associated with flying, the system will need to assess and act on that information itself. As the FAA approves more and more BVLOS waivers, they will move closer to rulemaking, where a new standard will need to be considered. In this case, Skydio and industry should always push for performance-based standards, rather than prescriptive standards.

Alex Fraess-Ehrfeld: For current BVLOS exemptions, regulators require an extensive assessment of the air and ground risk of the “operational volume” plus a “contingency volume”, exactly for such unexpected events. So, with increased density of population on the ground requirements for mitigation strategies are stricter. On top of this, AIR6 Systems’ larger systems are equipped with various layers of redundancy (all essential electronics, mechanical parts as well as communications) in order to mitigate system failure and provide a good base strategy for reliable BVLOS operations.

What are technology providers currently doing to mitigate the GPS jamming risk as they’re currently operating overpopulated areas?

Omer Sharar: Currently BVLOS is not allowed above people unless under very special (and rare) FAA waiver). Drone builders and operators use different approaches to cope with GPS jamming, amongst them are:

- When GPS is lost, assume manual control – when not flying full BVLOS, there should be an operator “standing by” ready to assume manual control.

- When GPS is lost, use camera to try to stay in place until GPS returns (what if it doesn’t simply return? What if it’s dark or optical conditions are poor for camera positioning?)

- When GPS is lost, open the parachute and land (results in many aborted missions, potentially land on someone’s head)

How will the role of drone service providers change via autonomy?

Alex Fraess-Ehrfeld: Service providers with IT skills and knowledge of data processing and interpretation will mature in their role and they will be able to do their work more efficiently and deliver better results. I see autonomy for many applications mostly supporting either a pilot, surveyor, inspector and any type of service provider.

What standards need to be in place to assess and manage risk and liability for the possibility that autonomy goes wrong?

Alex Fraess-Ehrfeld: Highest standards will be applied and lots of data will need to be collected first. And, autonomy needs to be monitored carefully, by operators in the field or in a control centre. In future, there will be one-on-one situations (one operator per drone) or as with swarms or a fleets of drones, depending on the complexity of the operations, one operator monitoring many drones. Only then we will be able to unleash the full autonomy potential and efficiencies.

Nevertheless, manufacturers will be very careful in using the term “full autonomy” for quite some time, and this will be a gradual step. Starting with certain part-sequences up to complex tasks and ultimately system-of-systems approaches. Not only regulation will require operator’s monitoring at all times but also system manufacturers will make sure that the operator will be responsible for the mission performance when autonomy is involved. Autonomy will be structured to support operators as much as possible so that navigation skill is secondary.

Click here to watch or listen to the webinar.

Comments