The value of drone technology is tied to the future ubiquity of it, as experts have long talked about how the technology needs to be positioned as just another tool to be utilized as needed in order to truly unlock that value. Getting there is a matter of knowing that drones are as safe to use as any of those other tools though, which is why the FAA is focused on being able to quantify that kind of safety. Thankfully, as a recent study conducted by State Farm at one of Virginia Tech’s impact labs shows, there’s hard data to make that safety case.

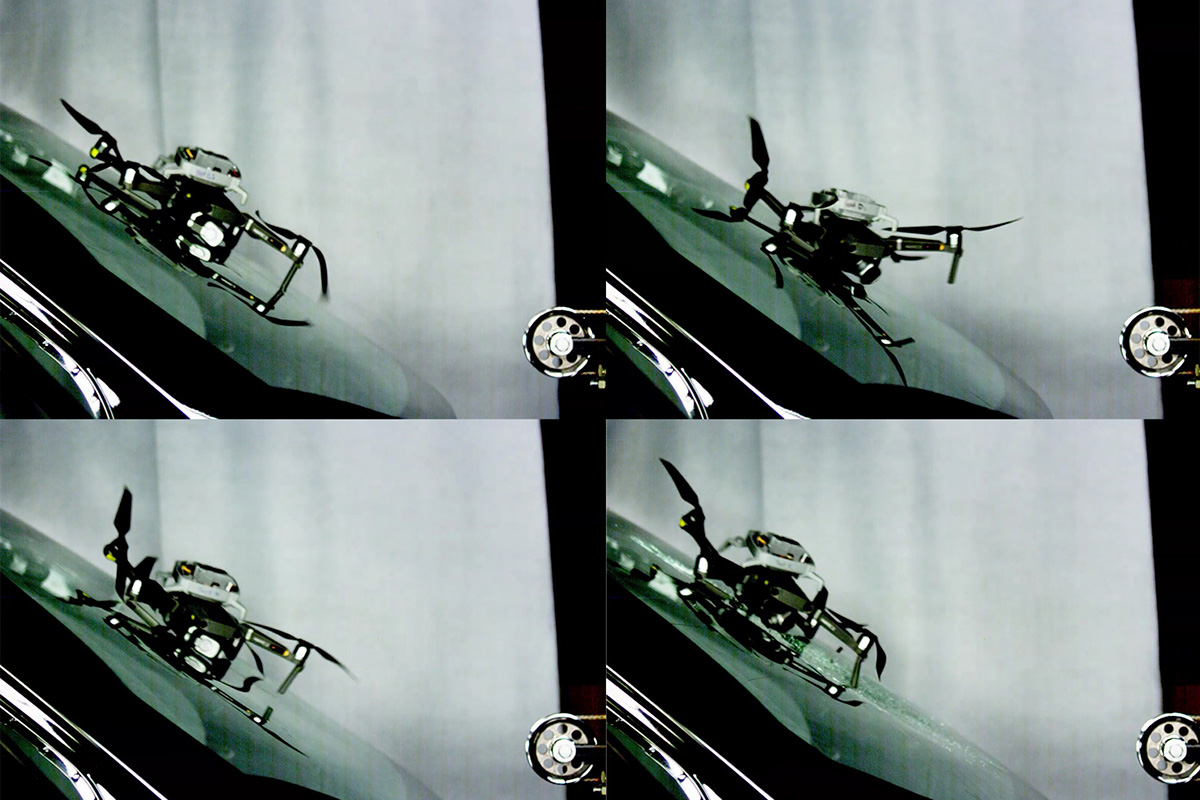

This study by the Virginia Tech Mid-Atlantic Aviation Partnership (MAAP) and State Farm saw the development of unique test methods to assess the risk of a drone impact with a moving vehicle. The data from these tests supported State Farm’s successful application to the FAA for a waiver to a previous provision of 14 CFR Part 107 prohibiting drone flights over moving vehicles. The results of the test are telling on multiple levels.

“Post-impact inspections from the study showed an interesting result,” said Dave Phillips, State Farm spokesperson. “At impact speeds between 25 and 62.5 mph, the only signs of the collision were streaks of rubber and plastic transferred from the drone as it slid up the glass. When the Mavic hit at 67 miles per hour, a web of cracks shot across the windshield as it bowed inward, spitting shards of glass onto the floor. The slim margin between a virtually pristine windshield and a destroyed one drew a clear boundary around low-risk scenarios. The waiver application reasoned that as long as potential relative impact speeds never exceeded 62 mph, flights over moving vehicles presented minimal risk. The FAA agreed.”

State Farm is no stranger to drone technology, as the company has been making efforts to utilize drones since 2015, when they were the first insurer to receive FAA approval to operate drones for commercial use. In 2018, State Farm was part of a team selected for the FAA’s drone Integration Pilot Program (IPP) while in 2019 the company received a national waiver that allowed the company to conduct drone operations over people (OOP) and flights beyond the pilot’s visual line of sight (BVLOS). They continue to expand their use of drone technology to help their customers and manage their business efficiently, which this study will go a long way towards defining.

The data demonstrated that a small parachute-equipped drone won’t actually damage a car traveling at average in-town speed limits. This finding helps address safety concerns related to flying drones over moving vehicles, but there are still limitations when flying over people.

“Drones are safe to use for claim assessments and inspections when flying over vehicles in areas where speed limits are less than 62 mph,” Phillips told Commercial UAV News. “The speed at which a drone would hit a windshield is the sum of the vehicle’s speed and the speed of the wind pushing the drone toward it. In the average suburban neighborhood, with speed limits between 25 and 35 mph, even the maximum wind speed the drone can tolerate — about 23 mph — would still keep potential impact speeds below the 62 mph threshold.”

The FAA has been very open and receptive to these sorts of safety cases that have been developed by State Farm and Virginia Tech. This type of research directly supports the FAA’s work to encourage innovation while also balancing safety concerns to help ensure that drones can be utilized in numerous commercial applications. Improving safety through the use of technology is always at the forefront of their research to support these uses, but the effects go far beyond these specific applications of drone technology.

“To make the case for a new operation, you need quantitative data about potential risks,” said Tombo Jones, MAAP’s director. “When we started this project, there was no data we were aware of that addressed the effects of a collision between a drone and a car. The test methods we developed to get that data were critical for this particular use case, but they also helped establish a foundation for empirically evaluating impact risk. Those principles, which can be adapted for a variety of scenarios, will be valuable as drone operations expand.”

Right now, State Farm utilizes drones to do everything from conducting individual roof inspections to help assess large-scale damage after catastrophes to assist with risk modeling so that their customers can make informed decisions to help mitigate losses before they happen. As Jones said though, these lessons will be applicable for numerous scenarios across multiple industries.

Data from studies like the ones developed by State Farm and Virginia Tech help operators, organizations and the general public understand the drones can be both safe and reliable when flying over moving vehicles. Doing so is helping to build a complete a safety case to the FAA involving expanded operations over people that will ensure drones achieve the ubiquity that so many have forecasted will be as lucrative as it is empowering.

Comments