The Rising Threat Landscape: Drivers of CUAS Investment and Urgency

Counter Unmanned Aircraft Systems (CUAS) have become one of the fastest-growing areas of security investment worldwide.1 2Governments, agencies, and companies are investing significantly in the development of Collaborative Unmanned Aerial Systems (CUAS) technologies. A prime example is the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) CUAS Grant Program that provides $500 million in funding to enhance state, local, tribal and territorial capabilities to detect, identify, track, and monitor UAS.3 Another is The Pentagon’s creation of an “Amazon-like” shopping portal for CUAS equipment.4 The surge in interest and investment in CUAS systems in the United States is largely driven by the heightened concern over drone attacks. This interest has been fueled by a complex interplay of technological proliferation, documented hostile use in conflict zones, high-profile security incidents, and an innate human fear of “robot killers” that have recently been characterized by the Secretary of the Army as “the threat of humanity’s lifetime.”5 6

- The Russo-Ukrainian War as a UAS / CUAS Proving Ground – The extensive, innovative, and high-volume deployment of both commercial and military UAS by both sides has underscored the foundational role of drones in modern warfare and their ability to inflict mass damage, significantly accelerating global CUAS prioritization.7 8

- Drone Weaponization by Non-State Actors (NSA) – Terrorist groups pioneered the widespread and organized use of commercial drones to deliver crude explosives and conduct surveillance, demonstrating the lethality and scale of the threat.9 10

- Rapid Technological Proliferation and Availability – The commercial drone market's rapid development, coupled with the low cost and ease of access to high-performance consumer drones, allows actors with limited resources to acquire powerful, weaponizable platforms.11

- The New Jersey Drone Sightings (Nov-Dec 2024) and Public Panic – A widespread series of reports of unidentified drones over sensitive and residential areas in the Northeast, initially sparked mass panic, federal investigation, and an emergency flight restriction, which highlighted the vulnerability of US domestic airspace and the lack of transparent, immediate federal response.12 13

- Critical Infrastructure & High-Profile Sporting Event Threats – The recognition that drones pose a direct threat to high-density public gatherings and major sporting events (e.g., World Cup 2026,14 LA 2028 Olympics15) has driven government initiatives and major funding to equip local authorities with CUAS detection and mitigation capabilities.16 17

- The Threat of Drone Swarm Attacks - The potential for adversaries to use coordinated swarms—multiple autonomous drones—to overwhelm traditional, singular defense mechanisms has created a significant national security challenge, driving extensive research into sophisticated C-UAS solutions.18 19

- High-Profile Airport and Sensitive Airspace Incident – Specific malicious or unauthorized drone incidents at airports (e.g., Gatwick, Brussels), military bases, and over wildfires (LA Fire drone and scooper collision20 21) have exposed a clear vulnerability to drone-centered economic, defense, and public safety disruptions.22

- Absence of Established National Legal and Policy Frameworks – The complexity of the challenge is amplified by the fact that many effective CUAS technologies, such as jammers, are currently illegal for most non-federal entities in the U.S. This legal gap is driving a major legislative push to grant necessary permissions to protect critical assets.23 24

- The Dual-Use Nature and Challenge of Intent – The inherent difficulty in rapidly detecting, tracking, and correctly identifying the intent of a small, fast-moving UAS in a congested airspace, often indistinguishable from legitimate commercial or hobbyist drones, drives the need for sophisticated, layered, and integrated CUAS systems.25 26

While these heightened concerns have resulted in significant funding and policy focus being directed to increasing CUAS capabilities and use authorities, there is one aspect of this sector that has been largely excluded from the conversation: rules of engagement (ROE).

Rules of Engagement: Bridging Military and Civilian Protocols

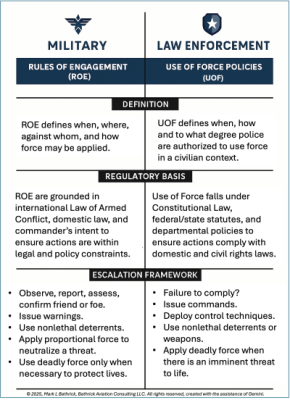

As drones become ubiquitous in commerce, public safety, infrastructure inspection, and recreation, the challenge of distinguishing benign operations from asymmetric threats has intensified.27 In this context, Rules of Engagement (ROE), traditionally military directives governing when and how force may be applied, and Use of Force (UOF), a law enforcement framework grounded in constitutional and statutory limits must be understood not as competing doctrines but as complementary tools.28 While ROE typically applies to military operations overseas and UOF governs domestic law enforcement actions, counter-UAS (CUAS) operations in U.S. airspace demand a hybrid approach.29 The sheer volume of drones, coupled with their potential for misuse, means that CUAS responses must be calibrated to avoid tragic overapplication of force, whether kinetic or electronic. This requires blending ROE’s escalation logic with UOF’s proportionality and necessity standards, supported by robust decision frameworks, operator training, and real-time data analytics.30 Without this synthesis, the risk of misidentifying a delivery drone as a threat or failing to act against a weaponized one remains dangerously high.

ROE are directives issued that define the circumstances, conditions, degree, and the way force, or actions that might be construed as provocative, may be applied.31 In simple terms, ROE provides the "when, where, how, and why" forces can engage a target. They are an operational framework that ensures the use of force aligns with national policy, strategic objectives, and legal obligations.

ROE is traditionally a military term, used to provided forces with the necessary weapons release/use guidance when deployed in potentially hostile situations. The military has developed CUAS ROE that is applicable both abroad and within the United States.32 The law enforcement equivalent to ROE is “use of force” (UOF) policies. While ROEs are grounded in international law (e.g., Law of Armed Conflict, Geneva Conventions) and national policy, UOFs are based on constitutional law (Fourth Amendment), federal, state, and local statutes, case law, and local department policies. UOF policies are designed for civilian contexts, where the emphasis is on protecting rights, minimizing harm, and ensuring due process under the Constitution. ROE are designed for combat or quasi-combat environments, where lethal force may be authorized against hostile actors. The goal of each is to ensure actions are legally justified, proportional, and accountable.

Drones uniquely invert the traditional risk balance between operators and targets, eliminating the attacker’s personal vulnerability while exposing the defender to sudden, asymmetric danger. This presents a challenge for traditional law enforcement use-of-force policies, as seen in the Russo-Ukraine War where drones were used in coordinated swarms. Law enforcement frameworks are designed for civilian contexts, emphasizing proportionality and direct human confrontation, whereas military rules of engagement in counter‑air and air defense applications are explicitly structured to manage rapid identification, classification, and neutralization of aerial threats under conditions of uncertainty and massed attack. Military ROE provide the doctrinal flexibility, escalation authority, and operational clarity necessary to respond decisively to drones that can be deployed remotely, at scale, and without risk to their operators—making them far more aligned to the realities of CUAS engagements than the civilian policing standards that lack both the scope and the speed required for such threats. For these reasons, we will use ROE in discussing CUAS engagement protocols.

Rules of Engagement: Lessons Learned at Both Ends of the Barrel

This was the question I asked as a newly minted 23-year old Navy fighter pilot when the Judge Advocate General (JAG) came into our ready room to deliver the required briefing on all the requirements that had to be met before we could employ our weapons, even in self-defense. You mean it wasn’t as clear cut who the bad guys were as it was in the movies? Not only did we have to endure a lengthy legal briefing, but we also had to take and pass a post test. Moreover, ROE exercises became an integral part of our airborne intercept training, where we worked closely with our air controllers on various and often complex ROE scenarios.

I soon learned first-hand “at both ends of the barrel” why ROE was not only important, but often difficult in application. Less than a month into my first overseas carrier deployment, we were rushed to the coast of Lebanon following the bombing of the multinational force barracks that claimed 307 lives (including one of my USNA classmates).33 Tensions were high, especially since there were speculations that terrorists might attempt to use a suicide plane against our carrier or one of the other ships. In support of the multinational force and our ships off the coast, a 24-7 defensive counter air posture was established with airborne fighter aircraft and surface-to-air missile equipped ships, both on constant high alert. During one of these flights, I was directed toward an unidentified aircraft (bogey) that was rapidly approaching our carrier. As the distance narrowed, and the bogey continued toward our ship, I was authorized to arm my air-to-air missiles, leaving only the trigger pull to launch a missile against the target if it could not be identified as friendly. Following the ROE briefing we had received and numerous ROE training flights, we rendezvoused with a friendly Lear Jet that had been supporting allied training exercises but had strayed from its designated operating area, unknowingly putting itself in grave danger of being shot down. I will never forget the sense of relief as I returned the “Master Arm” switch to its guarded off position. If we had not understood, followed, and trained to the ROE, we might have mistakenly shot down a friendly aircraft.

That deployment also taught me about the limitations and vulnerabilities of electronic detection, identification, and tracking, as well as what it feels like being on the receiving end of the ROE equation. One night, returning to the carrier from a combat air patrol (CAP) mission, we received an emergency call on the guard frequency from one of our accompanying ships. They reported that an “unidentified” aircraft at a specific position was about to be engaged with missiles. We quickly realized that WE were that aircraft and that even though all our electronic identification gear had been independently verified by numerous other assets, this “robo-cruiser” (as we affectionately called it) was not picking us up as a “friendly.” Thankfully, between our radio calls and aggressively maneuvering our Tomcat in the other direction, we were not fired upon. Forty-one years later, this scenario repeated itself, but to a much less desirable conclusion with the USS Gettysburg shooting down an F/A-18F.34 These incidents provided numerous lessons on the role of ROE. Not only is ROE challenging to formulate, but it also demands training and discipline to ensure safe and effective execution. Additionally, electronic means of detection, identification, and tracking are not foolproof, and relying solely on them as a single data source for targeting decisions can be hazardous.

The Tragic Real World Consequences of Failed or Unpracticed ROE

Throughout history, failed or unpracticed Rules of Engagement (ROE) have led to tragic consequences. These incidents underscore the critical importance of disciplined and layered ROE frameworks, especially in complex airspace operations and where decisions must be made in seconds. Below are several well-documented cases that illustrate the devastating cost of ROE breakdowns:

- Ukraine Int'l Airlines Flt PS752 - Jan 8, 2020 - Tehran, Iran – 176 killed.35

- In a high-tension environment following an Iranian missile attack on U.S. bases, an IRGC air defense unit misidentified the civilian Boeing 737 as a U.S. cruise missile. The unit, facing a communications breakdown, acted on flawed ROE and fired without receiving clearance from central command.

- Siberia Airlines Flight 1812 - Oct 4, 2001 - Black Sea – 78 killed.36

- During a Ukrainian air defense exercise, a surface-to-air missile was accidentally fired at the civilian Tu-154. It was a catastrophic failure of training ROE and safety protocols, tragically demonstrating the danger of live-fire systems.

- Black Hawk Shootdown – April 14, 1994 – Northern Iraq – 26 killed.37

- Two U.S. F-15s enforcing the no-fly zone shot down two U.S. Army Black Hawk helicopters. The F-15 pilots, operating under ROE that allowed engagement of non-friendly aircraft, misidentified the helicopters as hostile Iraqi Hinds, despite functioning IFF (Identify Friend or Foe) systems.

- Iran Air Flight 655 – July 3, 1988 – Persian Gulf – 290 killed.38

- The U.S. Navy cruiser USS Vincennes, operating in a tense naval engagement, misidentified the civilian Airbus A300 as an attacking Iranian F-14 fighter. Operating under restrictive ROE but in the "fog of war," the crew believed they were acting in self-defense.

Domestic Drone Defense: Navigating the Homefront Maze

Domestic CUAS operations in the U.S. are far more complex than overseas military scenarios. I experienced this first-hand as the architect of the U.S. Department of the Interior’s (DOI) “Drones for Good” program and DOI Director of Aviation. In the early 2000’s we began to see consumer drones over National Park Service lands, like the National Mall. Soon I started receiving questions from law enforcement about whether these drones could be “taken down.” In addressing these questions, I came to realize how much more complicated domestic “counter-air” ROE was. This complication was exemplified by the infamous gyrocopter landing near the Capitol Building in 201539 and repeated instances of children and their families coming to the National Mall to try out their new birthday/Christmas drone, unaware they were flying in prohibited airspace.40 Unlike overseas combat zones where ROE are shaped by the Law of Armed Conflict and the presence of hostile actors, domestic CUAS engagements often occur over densely populated areas filled with civilians, public venues, and vital infrastructure, none of which can be treated as expendable or collateral damage. Every person and structure under U.S. airspace is protected, raising the stakes for any CUAS action.

Reports have consistently highlighted the extreme difficulty in creating a safe and effective ROE for CUAS use within the United States due to several factors, including:

- The Problem of Identification (Friend or Foe): The single greatest challenge. How do you distinguish a hobbyist's drone from a terrorist? Unlike traditional aircraft, most drones lack "squawk" transponders or a clear "friendly" signature. A drone delivering a package looks identical to one delivering a bomb.

- The "Clutter" Problem: The low, slow, and small nature of drones makes them difficult to track in urban environments. A radar often sees a drone, a bird, and a plastic bag as similar "clutter." Likewise, with visual and acoustic sensors a false positive could lead to engaging the wrong object.

- Legal and Jurisdictional "Nightmare": Who has the authority to shoot down a drone? The DoD is barred by Posse Comitatus from engaging outside strict authorities that were granted to it under Title 10 U.S. Code.41 The FAA "owns" the airspace, DHS/FBI "own" the domestic threat, and local police "own" the ground. While DOJ and DHS were granted CUAS authorities in the 2018 FAA Reauthorization Act, Congress allowed those to expire on September 30, 2025.42 Together, this creates a frustrating legal morass that can lead to deadly inaction or over-reaction.43 44

- A "Weaponized" National Airspace (NAS): An effective CUAS system (jammer, laser, projectile) "weaponizes" the airspace.45 Using it risks collateral damage to legitimate air traffic (planes, helicopters, other drones) that may rely on the same GPS or radio frequencies.

- Collateral Damage (On the Ground): What goes up must come down. A "killed" drone (whether jammed or shot) becomes a 1-1,320 lb. (under the provisions of the BVLOS NPRM) object falling uncontrollably over a populated area, stadium, or critical infrastructure. This dramatically elevates the stakes of any kinetic CUAS action. A CUAS projectile fired to neutralize a drone could continue downrange and strike a school, hospital, or pedestrian; debris from a damaged drone could fall onto crowds or ignite fires; and electromagnetic mitigation could disrupt nearby communications, medical devices, or aviation systems.46 47

Domestic drone defense in the US faces unique challenges compared to overseas military operations. Unlike combat zones, domestic CUAS engagements often occur in densely populated areas, making the stakes high. Identification is difficult, as most drones lack clear identification signals. Small and slow drones blend in with birds or debris, increasing false positives. Legal and jurisdictional confusion complicates matters, with overlapping authorities and gaps in legislative authority. CUAS deployment risks collateral damage, both in the air and on the ground. These factors create a high-stakes environment, requiring clear rules of engagement, robust identification protocols, and careful coordination.

How do the System Elements of CUAS Facilitate ROE-Conforming, Time-Sensitive Decisions?

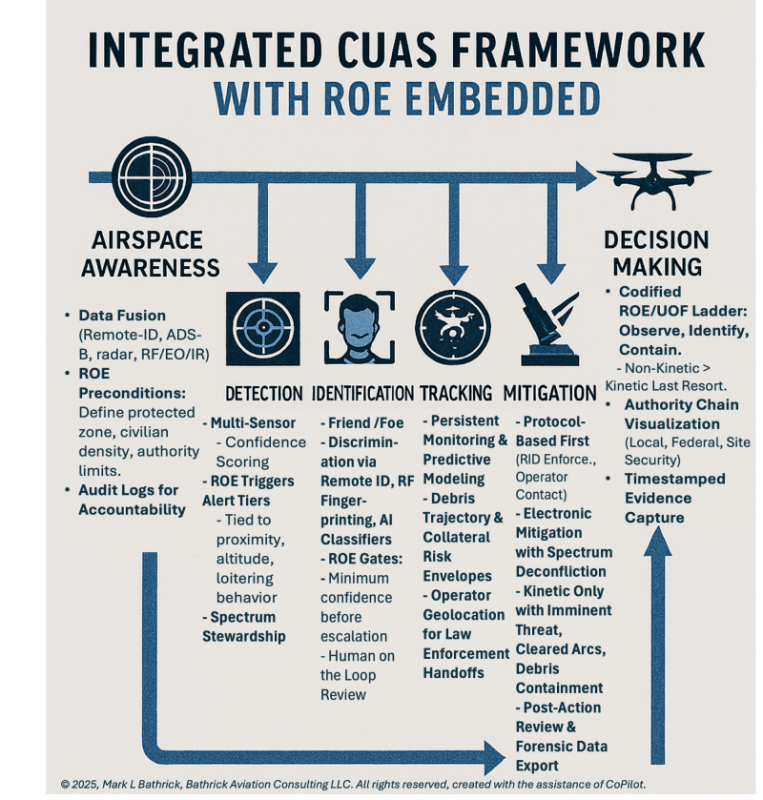

Airspace awareness, the ability to perceive everything within your airspace, serves as the bedrock for time-sensitive ROE decision-making. It provides a real-time snapshot of all aerial activities, seamlessly integrated from radar, RF, ADS-B, Remote ID, and UTM feeds. This situational layer allows operators to distinguish normal traffic from anomalies.48

Most CUAS frameworks ignore airspace awareness, assuming this is a feature that exists across the national airspace system (NAS). Unfortunately, the U.S. lacks fundamental airspace awareness across 96% of its low altitude airspace. This is not due to technological gaps, but because Federal Regulations continue to permit manned aircraft operating under visual flight rules (VFR) in Class G uncontrolled low altitude airspace (representing 96% of all U.S. low altitude airspace) to operate with “electronic invisibility” (see Commercial UAV News: The Elephant in the Airspace: How Outdated Approaches Ground America's Aviation Leadership). This is an unsettlingly fact when you consider that on 9/11, manned aircraft operating at low altitudes flew undetected and conducted terrorist attacks on American soil, resulting in the loss of thousands of lives. Moreover, manned aircraft have proven remarkably easy to convert into drones.49

And since the robust radar and air traffic surveillance system that blankets the traditional airspace used by commercial and private aircraft, airspace awareness in the low altitude economy is at best, fragmented and inconsistent.

Detection then isolates potential threats using multi-sensor inputs (e.g., RF, EO/IR, radar, acoustic) and flags objects that violate airspace parameters or exhibit suspicious behavior.50 Once detected, identification becomes vital: distinguishing between friendly, benign, and hostile drones using metadata, signal analysis, and AI-enhanced classification models.51 Tracking ensures persistent monitoring of the drone’s trajectory, speed, and proximity to protected assets, enabling predictive modeling and escalation-of-force logic.52 Finally, mitigation, whether kinetic, electronic, or protocol-based must be precisely timed and proportionate, minimizing collateral risk to civilians and infrastructure while neutralizing the threat. Together, these elements form a layered decision support architecture that enables operators to act within ROE constraints, avoid tragic missteps, and preserve airspace sovereignty.

The Current Disconnect in U.S. CUAS Discussions

CUAS messaging across vendor websites and conference agendas focuses on capabilities rather than operational decision frameworks or domestic engagement constraints. Media roundups highlight radars, RF sensors, advanced jamming, and mitigation technologies as proof of maturity but fail to explain how these capabilities support proportionality standards, timing windows in populated environments, and necessary ROE-supportive action decision-making and governance for domestic CUAS use cases. DHS S&T’s program pages highlight testing, pilot projects, and authority pathways to assess kinetic and non-kinetic mitigation, focusing on technology rather than ROE/UOF decision flows unique to U.S. venues. CUAS conference agendas mostly focus on doctrine, capability integration, and threat case studies, rarely addressing deep treatment of domestic ROE, civilian protection requirements, or law enforcement decision support beyond high-level mentions.53 54

DoD’s Counter sUAS Strategy acknowledges the need for solutions beyond material resources, emphasizing doctrine, training, and policy. However, it frames the problem across “homeland, host nations, and contingency locations” without providing public, detailed ROE guidance for domestic civilian airspace media.55 The Congressional Research Service primer on DoD counter UAS outlines authorities, organizational roles, and system portfolios, focusing on acquisition, coordination, and testing maturity rather than codified ROE/UOF decision trees for off base or mixed civilian environments.56 DHS S&T’s CUAS page references legal authorities and testing pathways for kinetic and electronic mitigation, but its public materials emphasize evaluation and deployment mechanics rather than granular domestic ROE constraints for crowded urban contexts.57 58 Federal, State, and Local Agencies currently lacking CUAS authorities are ill-equipped to develop their own ROEs and corresponding CUAS system frameworks. Moreover, as those Federal Agencies with current or previous CUAS haven’t developed a comprehensive set of domestic U.S. CUAS ROEs and CUAS system frameworks, they have little to draw from in developing their own.

Closing the Gap - A Strategy for Developing a Balanced Domestic CUAS ROE

A successful domestic CUAS ROE must be built on a "safety-first," law-enforcement-based model, not a military combat model. The goal is to mitigate threats while protecting people and property from undue harm as an outcome of these actions.

PHASE 1: Establish the Legal and Technical Foundation

1. Clarify Authority via Legislation: Congress must pass clear laws designating which federal agencies (DHS, FBI, DoD) have authority, and under what specific circumstances, to employ CUAS. This must include exceptions to existing laws and strict oversight.

2. Mandate "Universal Electronic Conspicuity": The FAA must finalize and mandate Electronic Conspicuity for ALL aircraft. This is the lynchpin of any ROE, as it provides the foundation upon which all other elements of CUAS components rely: Airspace Awareness. It is also something that can be swiftly implemented within existing federal authorities. (see Commercial UAV News: Reclaiming the Skies” Accelerating Universal Electronic Conspicuity for America’s Low-Altitude Aviation Safety, Security, Prosperity, and Leadership). You can’t effectively detect, identify, track, and mitigate threats in your airspace if there are assets flying in this airspace that are allowed by regulation to remain invisible, when there is available and cost-effective technology to address this gap.

3. Tap into the Power of a Cross-Domain Digital Infrastructure Approach.

- Leverage available digital information/intelligence from assisted/autonomous ground vehicles, smart buildings, infrastructure, and cities (see: The Importance of a Cross-Domain Digital Infrastructure, Business of Automated Mobility, September 28, 2022)

4. Tiered Risk-Based Classification: Define "no-fly" zones by risk, not just location.

- Level 1 (Nuisance/Careless): A hobbyist straying near a stadium. ROE: Detect, track, and locate the operator for law enforcement action on the ground.

- Level 2 (Reckless): A drone interfering with firefighting or a hospital. ROE: Use non-kinetic "soft kill" (e.g., focused jamming) to force a landing only if ground risk is low.

- Level 3 (Imminent Credible Threat): A drone with a clear payload approaching a protected target (e.g., the President). ROE: Authorize kinetic "hard kill" (net, laser, projectile, etc.) as a last resort, with a clear chain of command.

PHASE 2: Develop the Operational Framework

- Create an Integrated Chain of Command: Establish clear "joint" command structures (DHS, FAA, FBI, Local PD) for high-risk events (Super Bowls, etc.). No single entity can act alone.

2. Adopt a "Law Enforcement" Threat Assessment: Train operators to use a "Totality of the Circumstances" model. An unknown drone is just unknown. An unknown drone + flying erratically + in a high-security zone + ignoring warnings = a threat.

3. Prioritize "Soft Kill" and "Left of Boom": The ROE must mandate the use of the least invasive/damaging mitigation possible. The primary goal is to detect and locate the operator ("left of boom") rather than dealing with the drone itself ("right of boom").

4. "Positive Identification" (PID) is Mandatory: ROE must state that no engagement (soft or hard) can occur unless the target is positively identified as a threat or is in a pre-defined, "last resort" kill box where any drone is deemed hostile.

PHASE 3: Implement, Train, Train, Train, and Refine, Update, Train, Train, Train

1. Mandatory, Standardized Training: All authorized CUAS operators must undergo rigorous, standardized training and certification, with a strong emphasis on de-escalation, legal boundaries, and identifying civilian aircraft. As I learned during my military career, executing ROE requires training to the level of muscle memory to prevent panic and tragic outcomes when unexpected situations arise. Similarly, CUAS authorized agencies should be mandated to develop and regularly exercise ROE mishap plans for instances where CUAS actions may go awry. This requirement not only reminds agencies of the significant responsibility associated with these authorities but also provides valuable practice in effectively responding to such situations, akin to having and exercising an aircraft mishap plan.

2. Rigorous Testing & Pilot Programs: Before deploying test systems, thoroughly test them in controlled, “live sky” environments. Pilot programs at airports and critical sites can be conducted to gather data and refine the ROE based on real-world results.

3. Public Transparency and Oversight: All CUAS use must be subject to oversight and regular public reporting (e.g., how many times systems were used, and for what reason) to maintain public trust.

Beyond Technology: Embedding Rules of Engagement for Safer, Smarter Airspace Protection and Response at Home

The contrast between overseas CUAS operations and domestic U.S. scenarios underscores a critical gap in our current approach: while industry and government continue to emphasize technological detection, tracking, and mitigation capabilities, far too little attention has been devoted to the formulation, training, and integration of ROE across every element of these systems. The tragic consequences of failed or unpracticed ROE in complex, low‑altitude airspace environments demonstrate that technology alone cannot safeguard the public or ensure lawful, proportionate responses. To truly support time‑critical decision making, ROE considerations must be woven into airspace awareness, detection, identification, tracking, and mitigation layers, transforming them from isolated technical functions into a cohesive, accountable framework. Closing this gap requires a deliberate effort to instill balanced, domestic‑aligned ROE that promotes both safety and security—ensuring that CUAS systems not only neutralize threats effectively, but also uphold the principles of restraint, proportionality, and public trust that are essential in the U.S. homeland context.

Comments