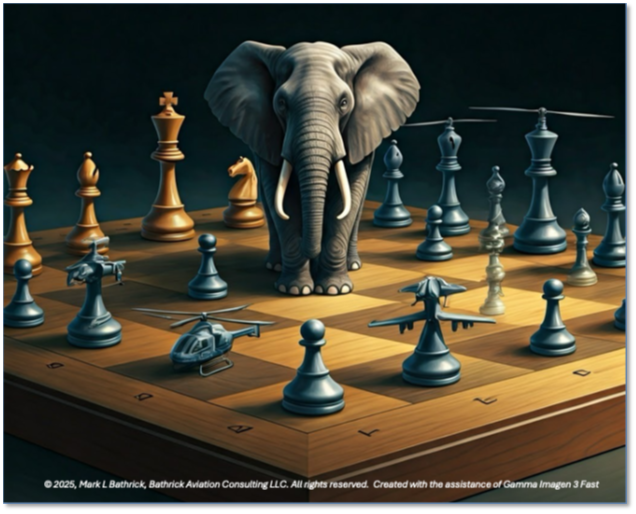

“Can we talk?” That’s often how awkward conversations about “the elephant in the room” begin. Well, in the United States we have an “elephant in the airspace.” So, “can we talk?”

Imagine a scenario where modern automobiles, equipped with advanced navigation, collision avoidance systems, and high-speed capabilities, are legally compelled to operate in a way that compensates for the technological shortcomings of horse-drawn carriages and riders on a bustling highway and must yield to them because that form of road transportation and commerce was “here first.” This is not a quaint historical anecdote but a vivid analogy for the current state of American aviation. The United States airspace structure and its foundational flight operating rules, largely conceived over half a century ago to fit the technology and markets of a bygone era, are now acting as an unspoken, yet colossal, obstacle—an "elephant in the airspace"—hindering the nation from taking a leadership role in Unmanned Aircraft System (UAS) and Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) development and integration. The practice of attempting to shoehorn these technologically advanced new entrants into an outdated airspace structure is not merely a disservice; it is actively holding the U.S. back from realizing the full leadership potential of its aviation future.

A Legacy of the Skies: How the Elephant Took Root

The story of the U.S. airspace system is one of progressive, albeit reactive, development, shaped by the evolving needs and limitations of early aviation. Fatal accidents were a routine occurrence in those early days.[i] This era of unregulated, often dangerous, flying practices, characterized by "barnstorming," necessitated federal intervention.

The Air Commerce Act of 1926 granted the Department of Commerce the authority to regulate aviation, setting crucial safety standards, licensing requirements for pilots, and airworthiness certificates for aircraft.[i] Further solidifying federal authority, the Federal Aviation Act of 1958 established the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), entrusting it with the comprehensive control and use of navigable airspace within the United States.[ii] This led to the creation of the National Airspace System (NAS), designed to protect persons and property on the ground while establishing safe and efficient airspace for civil, commercial, and military aviation.

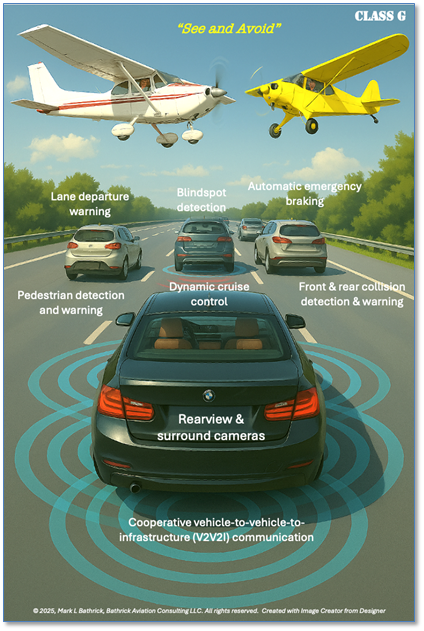

From the very genesis of aviation, the principle of "see-and-avoid" served as the predominant method for deconfliction and collision avoidance.[iii] This ancient concept, borrowed from maritime practices, relies entirely on the human pilot's ability to visually detect other aircraft on a conflicting flight path and initiate evasive action without external assistance. In the early history of flight, this was often the only available means of preventing collisions. Even as aviation advanced, "see-and-avoid" remained a fundamental, albeit limited, defense, particularly for aircraft lacking modern communication or situational awareness technologies.

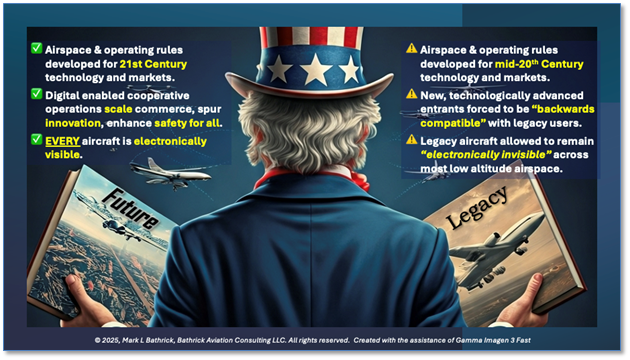

The development of the U.S. airspace structure and regulations has been a reactive process. This incremental approach, while effective for its era, created a significant "legacy debt." Principles, such as "see-and-avoid," and the structural classifications of airspace were designed for a specific paradigm centered on human-piloted aircraft and the technologies and markets of the mid-20th Century. When advanced technologies, like UAS and AAM, and their new markets emerged, the existing framework struggled to adapt, as it was not built with such disruptive future innovations in mind. This explains the deep entrenchment of the "elephant"—it is not merely a set of old rules, but a deeply ingrained regulatory philosophy that was purposefully constructed to be slow to change.

The Digital Revolution Takes Flight: “Democratizing the Third Dimension”

The early 2000s ushered in a period of unprecedented technological convergence, inadvertently laying the groundwork for the modern drone and AAM revolution in what has been referred to as the “2nd Golden Age of Flight.” [iv] The widespread adoption of smartphones drove the miniaturization and cost reduction of critical components such as accelerometers, gyroscopes (Inertial Measurement Units or IMUs), GPS receivers, and high-resolution cameras.[v] Simultaneously, advancements in battery technology provided the energy density required for sustained flight, while electric motors became more efficient and autopilots more sophisticated.[vi] These consumer-driven innovations provided the essential, affordable building blocks for autonomous flight systems.

This technological confluence rapidly transformed drones from expensive, niche military or hobbyist devices into accessible tools for a vast array of commercial and recreational applications.[vii] The proliferation of affordable, user-friendly drones has effectively "democratized the third dimension".[viii] What was once the exclusive domain of highly trained pilots and prohibitively expensive aircraft is now accessible to a vastly broader spectrum of users, from recreational enthusiasts to businesses seeking efficient logistics, infrastructure inspection, or data collection. This opening of the lower skies has given rise to a burgeoning "low-altitude economy," with the potential for scalable, on-demand airborne alternatives to traditional terrestrial commerce, industrial, and public safety methods, that offer “better, faster, cheaper, safer” service for more people.[ix]

The Digital Revolution Collides With an Ill-Equipped Regulatory Framework

A unique aspect of this transformation was the unforeseen innovation originating from adjacent industries. The core components that enabled modern drones—IMUs, GPS, advanced batteries, and cameras—were primarily driven by the smartphone and broader consumer electronics sectors, not with aviation as their primary application. The aviation industry, with its historically long certification cycles and high barriers to entry, was not the primary incubator for these foundational technologies. This left the FAA's traditional, often reactive, regulatory framework inherently ill-equipped to anticipate and rapidly integrate innovations stemming from such external, fast-paced sectors. This created a systemic lag between technological capability and regulatory enablement, exacerbating the challenge of integrating these new entrants into the NAS.

Furthermore, the "democratization of the third dimension" presents a profound scale versus control paradox. This phenomenon has resulted in a massive increase in the number of airspace users, shifting from a relatively small, highly controlled, professional user base to a diverse, large, and less uniformly trained population of operators.[i] The existing airspace management system was designed for a limited number of large, crewed aircraft operating under strict control or "see and avoid" principles. It was not built to handle an exponential increase in smaller, often autonomous, and widely distributed air vehicles. The sheer volume and diversity of these new entrants fundamentally broke the assumptions of the legacy system. Attempting to apply the same control mechanisms and safety principles like "see and avoid" for unmanned systems, became unscalable and inefficient.

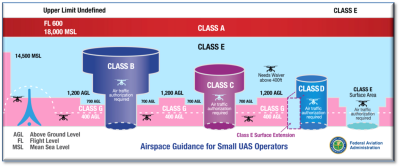

The Low-Altitude Labyrinth: Class G Airspace and the “Rule of the Lowest Common Denominator"

At the heart of the integration challenge lies Class G airspace, often referred to as uncontrolled airspace. This designation applies to any portion of the airspace not specifically designated as Class A, B, C, D, or E.[i] [ii] Its vertical extent typically ranges from the surface up to the base of the overlying controlled airspace, which can be 700 feet Above Ground Level (AGL) or 1,200 feet Mean Sea Level (MSL) in many areas, and even higher in extremely remote regions.[iii] [iv] A recent Commercial UAV News article estimated the ground coverage of these combined controlled airspace categories at 150,000 square miles.[v] This means that across the entire U.S., only about 4% of the airspace between the surface and 400’ (where most commercial and recreational drones operate) represents controlled airspace (Class B, C, D, E), leaving 96% as Class G uncontrolled airspace.

A critical regulatory disparity exists due to the inherent manned aircraft “electronic conspicuity gap” in Class G airspace.[vi] Manned aircraft, operating under Visual Flight Rules (VFR) in Class G below 10,000 feet MSL, are not required to be equipped with a radio, transponder, or Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B) Out.[vii] [viii] [ix] This legacy rule means manned aircraft operating in the low-altitude Class G environment are effectively "electronically invisible" to other aircraft, relying solely on the antiquated "see-and-avoid"

principle for collision avoidance.[i] This means that across 96% of the nation’s low altitude airspace, manned aircraft are permitted by Federal Regulation to operate with “electronic invisibility,” or no electronic conspicuity.[ii] Let that sink in.

This lack of a universal electronic conspicuity requirement for all aircraft flying in the NAS creates a disproportionate and unwarranted burden on technologically advanced new entrants. This regulatory paradox means that the most technologically advanced aircraft are forced into the most restrictive operational box precisely because the legacy aircraft they share the space with are not required to be electronically visible. This approach also carries significant adoption; economic and innovation costs as commercial and public safety drone operators are forced to incur the added costs to equip their drones and/or constrain their operations to compensate for regulations that give preference to these “lowest common denominator” legacy operators.

Beyond Human Eyes: The Safety Imperative of Universal Electronic Conspicuity

While "see-and-avoid" was a foundational principle in aviation, its inherent limitations have been recognized for decades by organizations like the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB).[i] Human eyes are subject to various constraints, including glare from the sun, clouds, haze, the aspect of the target object, blind spots, and the physical limitations of visual acuity. Visual scanning, even when systematic, often leaves large areas of the visual field unsearched, and is time-shared with cockpit instrument scanning. Crucially, studies from the 1970s concluded that "see-and-avoid" frequently failed to avert collisions as speed and other factors reduced the time to react.[ii] As air traffic density increases, the human capacity to identify and process all traffic inevitably becomes saturated, leading to an unacceptably high risk of collision.

The widening safety gap highlights that “see-and-avoid,” once a safeguard, is increasingly becoming a liability. We continue to see this in the aftermath of catastrophic aircraft midair collision accidents. Among the most recent tragedies was the unfortunate January 19, 2025, midair collision of an Army helicopter and a commercial airliner off the approach end of the runway at Reagan International Airport in Washington, D.C. On a clear night, this collision resulted in the loss of both aircraft and 67 fatalities. Despite both aircraft being equipped with ADS-B, the Army helicopter had its system turned off, rendering it electronically invisible. [iii] Consequently, the air traffic controllers were denied precise 4-D location information and were forced instead to rely solely on less accurate and latent radar data for situational awareness.

Lessons from the Automotive Industry

The automotive industry offers a compelling parallel in the rapid adoption of advanced safety technologies. Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems (ADAS) utilize automated technologies such as sensors, cameras, LiDAR, and radar to assist drivers and significantly enhance road safety.[i] Advanced technology features like blind spot monitors, front and rear collision detection and warning, automatic emergency braking (AEB), and lane departure warning have dramatically reduced accident rates by up to 56%.[ii] These systems have evolved rapidly since their introduction in the 1970s, with features becoming increasingly common by the 2000s and today representing essential components of modern vehicles.[iii]

Applying ADAS-like principles to aviation could leapfrog integration and revolutionize airspace safety and efficiency. The success of ADAS demonstrates that electronic detection and automated assistance can significantly improve safety in complex, high-density environments. Mandating universal electronic conspicuity for all aircraft in the NAS, particularly in the low-altitude economy, coupled with advanced airborne collision avoidance systems, could transform aviation safety. They would allow UAS and AAM to operate with far less restrictive rules, enabling widespread beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) operations and AAM services. Moreover, it would significantly reduce the workload on human air traffic controllers by shifting routine clearance tasks to automated, low latency and highly reliable systems.[i]

automated assistance can significantly improve safety in complex, high-density environments. Mandating universal electronic conspicuity for all aircraft in the NAS, particularly in the low-altitude economy, coupled with advanced airborne collision avoidance systems, could transform aviation safety. They would allow UAS and AAM to operate with far less restrictive rules, enabling widespread beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) operations and AAM services. Moreover, it would significantly reduce the workload on human air traffic controllers by shifting routine clearance tasks to automated, low latency and highly reliable systems.[i]

A Tectonic Shift: The New Aviation Landscape

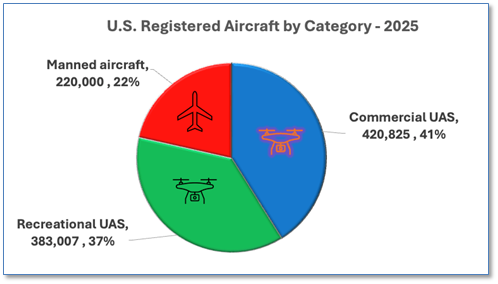

The United States aviation landscape is currently undergoing a profound demographic transformation. The numbers clearly indicate a rapid and significant shift in airspace user composition. As of April 1, 2025, there are over 1 million total drones registered in the U.S., a figure that includes 420,825 commercial and 383,007 recreational registrations.[i] This contrasts sharply with the estimated 220,000 registered manned aircraft in the U.S.[ii] It’s estimated that between 9% - 14% of these manned aircraft are legally not equipped with ADS-B Out.[iii]

Furthermore, current FAA data reinforces how drones have profoundly democratized access to the NAS. Since the FAA commercial rule (Part 107) was enacted in August 2016, the number of remote pilots in the U.S. has grown to 427,598 in 2024.[iv] In less than nine years, the number  of remote pilots has grown to the point that they make up more than 50% of all estimated active airmen certificates held.

of remote pilots has grown to the point that they make up more than 50% of all estimated active airmen certificates held.

This statistical inversion signifies a profound transformation in the aviation industry. The influx of numerous new entrants, each with distinct operational characteristics, including enhanced autonomy and autonomous safety features, predominantly low-altitude flight, and the potential for widespread adoption, necessitates a fundamental reevaluation of airspace structure and management.

The current regulatory framework, which prioritizes manned aircraft and treats drones as new entrants to be shoehorned into existing structures, is becoming increasingly misaligned with the reality of airspace usage and widely available advanced aviation technology.[v] Continuing this approach means that rules designed for a minority of users will dictate the operational parameters for the overwhelming majority, leading to systemic inefficiency and stifling the growth of what is becoming the dominant segment of future aviation.

Lack of Federal Progress Spurs Frustration and Counterproductive Actions

In the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012, Congress directed the FAA to “provide for the safe integration of civil unmanned aircraft systems into the national airspace system as soon as practicable, but not later than September 30, 2015.” [i] Nearly a decade later, this directive remains unmet and for many has served as the frustrating embodiment of regulatory paralysis. The FAA has also fallen short in educating and regulating drone operators as compared to manned aircraft pilots. Reports from government watchdogs and legislative analyses reveal that the FAA’s efforts have not effectively conveyed the intricacies of the NAS, leaving both commercial and recreational drone operators without the essential understanding of their shared responsibilities.[ii] [iii] Subsequently, the phrase “the clueless, the careless, and the criminal” emerged as a blunt critique of both drone operators who violated airspace regulations and the FAA’s failure to provide education and carry out enforcement.[iv] These combined frustrations have led to reactive legislative proposals like the Drone Integration and Zoning Act (DIZA),[v] TX House Bill 41,[vi] and FL Senate Bill 1422,[vii] which threaten to further paralyze progress toward fully integrating UAS into the NAS.

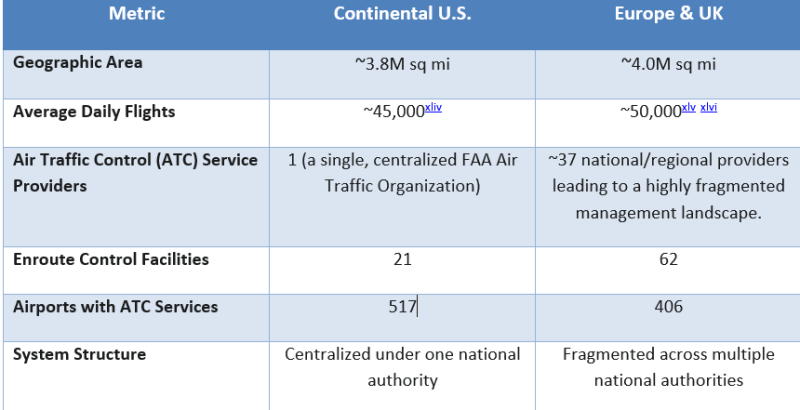

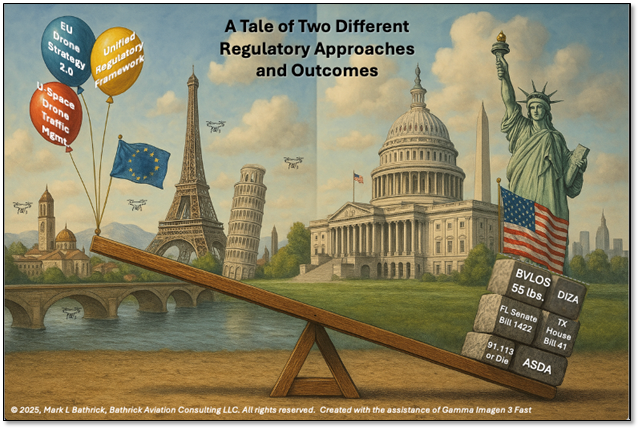

Critiques from industry stakeholders have also highlighted the impacts the FAA’s regulatory inertia has had on America’s aviation competitiveness and leadership in the world.[viii] This disparity was brought to light in a recent Commercial UAV News roundtable. The rapid progress achieved through the European Union’s harmonized risk-based approach was contrasted with the FAA’s traditional incremental approach.[ix]

In response, the FAA has often cited the complexity of the NAS. However, when you compare the characteristic aviation of the U.S. with Europe (including the United Kingdom), the complexity argument doesn’t hold up.

While the European Union (EU) faces similar (and sometimes more significant) challenges in integrating unmanned aerial systems (UAS) compared to the United States, it has successfully harmonized drone regulations across borders and established an EU-wide drone traffic management system (U-Space). Notably, the EU recently selected a Virginia-based company as its inaugural authorized U-Space Service Provider across Europe.[i] In contrast, progress in the United States has been limited to a fragmented array of projects.[ii]

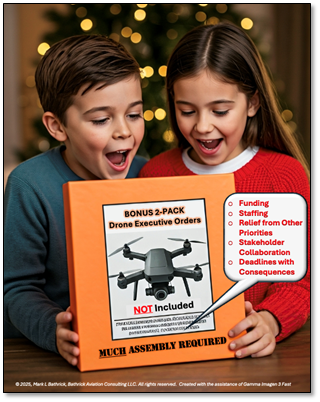

The Promise and the Limitations of the Recent “Unleashing American Drone Dominance” and the “Restoring American Airspace Sovereignty” Executive Orders (EOs)

Recently, two Presidential EOs were issued, which have generated widespread optimism about the future. The Unleashing American Drone Dominance EO promises to advance U.S. drone capabilities by accelerating integration into the NAS, supporting domestic manufacturing, streamlining regulatory processes, and promoting American drone exports. It also mandates swift regulatory updates to enable BVLOS operations, deploy AI-assisted waiver approvals, establish an eVTOL pilot program, strengthen the American drone industrial base, and prioritize U.S.-made drones in defense procurement.[i] While this Executive Order is a welcome and long-overdue step, its ultimate impact will be limited, even if everything in it is executed as planned. This is because BVLOS UAS must still operate within an antiquated airspace and regulatory framework that mandates new entrants be “backward compatible” with legacy users, rather than requiring all users to adhere to the currently available, affordable, and compatible technological standards for universal electronic conspicuity.[ii]

Likewise, the impact of the Restoring American Airspace Sovereignty EO will be similarly hindered. The first three essential elements of airspace sovereignty are detection, tracking and identification of what’s flying.[iii] While this EO instructs the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to take actions to restrict drone flights over critical infrastructure and  provide real-time access to UAS remote ID data to enforcement agencies, it fails to address the significant historical gap in American airspace regulations. This gap allows an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 manned aircraft to operate in accordance with FAA regulations without communication or electronic identification across 96% of the low-altitude airspace in the United States.[iv] September 11, 2001, was our wakeup call that aircraft can be used as weapons of mass destruction. Since then, warfare and terrorism have undergone a profound transformation with the widespread adoption of drones, including easily converted manned aircraft into precision weapons that can be launched from within country borders. [v] [vi] In light of these glaring aviation safety and security gaps, how can we continue to allow legacy aircraft, enabled by Federal regulations to operate without electronic conspicuity across vast portions of our low-altitude airspace?

provide real-time access to UAS remote ID data to enforcement agencies, it fails to address the significant historical gap in American airspace regulations. This gap allows an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 manned aircraft to operate in accordance with FAA regulations without communication or electronic identification across 96% of the low-altitude airspace in the United States.[iv] September 11, 2001, was our wakeup call that aircraft can be used as weapons of mass destruction. Since then, warfare and terrorism have undergone a profound transformation with the widespread adoption of drones, including easily converted manned aircraft into precision weapons that can be launched from within country borders. [v] [vi] In light of these glaring aviation safety and security gaps, how can we continue to allow legacy aircraft, enabled by Federal regulations to operate without electronic conspicuity across vast portions of our low-altitude airspace?

Conclusion: Charting a New Course for American Aviation Leadership

The "elephant in the airspace"—the deeply entrenched, human-centric, and visually-reliant regulatory framework—is no longer fit for purpose. It represents an outdated regulatory paradigm, a product of mid-20th-century technology and operational norms that actively impedes the 21st-century aviation revolution. The cost of clinging to this inertia is not merely inconvenience or missed opportunities; it is a forfeiture of America's historical leadership in aviation innovation and the loss of a significant economic advantage.

The path forward is clear: the U.S. National Airspace System must undergo a fundamental modernization that aligns it with the technologies and markets that did not exist when the current reclassification was enacted in 1993.[i] This requires a decisive shift from the limitations of "see-and-avoid" to universal electronic conspicuity for all aircraft, both manned and unmanned, particularly within Class G airspace. Such a mandate would level the playing field, allowing drones and AAM aircraft to operate with far less restrictive rules, thereby unleashing their full potential for safety and efficiency.

This simply cannot be accomplished with “more of the same.” The FAA's current approach, characterized by a "crawl, walk, run" philosophy and a reluctance to accept recognized risk mitigations, is proving too slow and ignores the safety data of nearly a decade of commercial drone flights.[ii] Continued attempts to jam new, advanced technology entrants into an airspace and operations paradigm that was conceived nearly 70-years ago will not serve us well.

The United States already has an agency that has been at the forefront of establishing and sustaining American leadership in aviation for over a century. Originally established in 1915 as the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), NASA was created in 1958 to explore and develop practical solutions to flight challenges. Since then, NASA has been instrumental in numerous significant safety and productivity advancements in U.S. airspace operations management, including:

· Terminal Area Productivity (TAP) program of the 1970’s

· Advanced Automation System (AAS) of the 1980’s

· Free Flight concepts of the 1990’s

· Airspace Systems Program (ASP) of the early 2000’s

· Unmanned Traffic Management System (UTM) of the 2010s

· Advanced Air Mobility (AAM), Advanced Capabilities for Emergency Response Operations (ACERO), System-Wide Safety (SWS), and the Digitally Enabled Cooperative Operations (DECO) programs of today.

Unlike the FAA, which was chartered as a regulatory body for the air transportation industry, NASA’s responsibilities specifically include driving economic growth in aerospace through technology development and transfer.[iii] NASA’s longstanding support for every advancement in airspace operations management positions it as a pivotal contributor to reestablishing America’s global leadership in aviation.

The United States stands at a critical juncture. It faces a choice: continue to operate under a legacy airspace system and operations management construct that is increasingly becoming a liability or proactively embrace a technology-first approach that recognizes and leverages the full capabilities of modern, technologically advanced aircraft. Moving forward necessitates:

(a) mandating electronic conspicuity for all aircraft in all airspace classes,

(b) adopting performance-based regulations that will enable us to surpass our current reliance on the escalating liability of a “see and avoid” center strategy,

(c) streamlining certification processes for novel technologies, and

(d) modernizing and investing in a networked, AI-driven, and digitally enabled air traffic management system capable of safely scaling to anticipated future high-density operations.

By making these decisive changes, the U.S. can move beyond the current “automobiles yielding to horses” mentality, better secure our skies, and truly lead the world into the era of the low-altitude economy, securing its future at the forefront of this 2nd Golden Age of Flight.

[i] Airspace Reclassification - Relearning Your ABCs, AOPA, April 5, 1993, accessed June 5, 2025 - https://www.aopa.org/news-and-media/all-news/1993/april/05/airspace-reclassification

[ii]Challenges to the Commercialization of Advanced Air Mobility - AIAA, accessed May 29, 2025, https://aiaa.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/1aiaa-challenges-to-the-commercialization-of-aam-digital.pdf

[iii]NASA Strategic Plan 2022 - https://www.nasa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/fy-22-strategic-plan-1.pdf?emrc=ff1a1e

[i]Unleashing American Drone Dominance, Executive Order by President Donald J Trump, June 6, 2025, accessed June 8, 2025 - https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/06/unleashing-american-drone-dominance/

[ii] Proven, Portable, and Perfectly Positioned: EC for Today’s Airspace, uAvionix blog, June 6, 2025, accessed June 16, 2025 - https://uavionix.com/proven-portable-and-perfectly-positioned-ec-for-todays-airspace/

[iii] Counter-Unmanned Aircraft Systems Technology Guide, Department of Homeland Security, Science and Technology & National Urban Security Technology Laboratory, CUAS-T-G-1, page 13, September, 2019 - https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/c-uas-tech-guide_final_28feb2020.pdf

[iv] How Many General Aviation Aircraft are in the United States, WikiWings, 2019, accessed June 10, 2025 - https://wikiwings.com/how-many-general-aviation-aircraft-are-in-the-united-states/

[v] Ukraine Appears To Be Using Light Planes Converted Into Reusable Bomber Drones, TWZ, by Howard Altman, April 26, 2025, accessed June 11, 2025 - https://www.twz.com/news-features/ukraine-appears-to-be-using-light-planes-converted-into-reusable-bomber-drones

[vi]Walking Into Spiderwebs: Unpacking the Ukraine Drone Attack, Lawfare by Nicholas Weaver, June 6, 2025, accessed, June 16, 2025 - https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/walking-into-spiderwebs--unpacking-the-ukraine-drone-attack

[i] European airspace hit a big milestone, and the U.S. drone industry should pay attention, by Sally French, May 11, 2025, accessed June 5, 2025 - https://www.thedronegirl.com/2025/05/15/european-airspace-anra-u-space/

[ii] Crowded Skies: Drone Operators in Dallas Share Airspace for First Time - First-of-its-kind implementation demonstrates a concept that could bring about more commercial drone operations, by Jack Daleo, May 28, 2025, accessed June 5, 2025 - https://www.flyingmag.com/crowded-skies-drone-operators-in-dallas-share-airspace-for-first-time/

[i] Public Law 112-95-Feb. 14, 2012, 112th Congress, Sec. 332 (a)(3), accessed June 4, 2025 - https://www.congress.gov/bill/112th-congress/house-bill/658/text

[i] Drones by the Numbers (as of 4/1/2025) | Federal Aviation Administration, accessed May 29, 2025, https://www.faa.gov/node/54496

Comments