On a recent article in Commercial UAV News, the author, Justin Call, made a very practical recommendation to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), to divide the implementation of Part 108 into two phases, namely Part 108A for rural areas and Part 108B for urban regions.

The recommendation has merit and even if the FAA does not accept it or implement it, the idea of a staggered implementation is solid and probably the way it will happen. Unfortunately, the FAA does not operate in ambiguous terms such as rural and urban, therefore we are venturing a more ‘aeronautical’ way of defining where Part 108A and Part 108B will be deployed.

To start, at the bottom of what we are trying to do in terms of operational safety is avoid collisions between crewed and uncrewed aircraft, therefore we must concentrate in the areas where these two distinct forms of aviation are bound to be closer to each other and that is during takeoff and landings of traditional aircraft. In other words, the areas where an encounter between a drone and an airplane is more likely to occur are the vicinity of airports.

This is a very precise metric because airports in the U.S. are clearly defined, plus they are classified in three separate categories, Class B, Class C and Class D.

Class B (pronounced Bravo) airports are considered the busiest and largest of the entire system, they normally cover a large area defined by a circle with a radius of 15 nautical miles from the center of the airport and multiple layers in a configuration known as the inverted wedding cake. As of January 2023, there were 37 Class B airports in the United States. This exclusion zone normally extends from surface to 10,000 feet, but there are many variations due to topography and many other factors.

Class C (pronounced Charlie) airports are regional airports which serve smaller cities around the country and are defined by a circle with a 10 nautical miles radius from the center of the airport. Currently there are 122 Class C airports in the USA. The exclusion zone for Class C airports extends vertically from the surface to 4,000 ft.

Class D (pronounced Delta) airports are mostly general aviation (GA) facilities and can have a tower or not depending on size and complexity of runway configuration. These airports are defined by a circle with a radius of 2.5 nautical miles from the center of the airport and an altitude of 2,500 ft. Currently there are 476 airports classified as Class D in the USA.

The exact number of these airports changes constantly as airports are re-classified, listed and delisted according to use and expansion or closure.

There are numerous other smaller classifications such as private airports and unclassified facilities, but these will have to be treated separately; they are approximately 14,400 private-use (closed to the public) and 5,000 public-use (open to the public) airports, heliports, and seaplane bases.

Using a bit of math, we can quickly calculate that the land area covered by these airports is as follows: Class B, 26,085 square miles, Class C, 38,314 square miles and Class D, 9,344 square miles for a total of 73,743 square miles. If we double that area to create an extra layer of exclusion around any airport, we have a total of 150,000 square miles that would have to be excluded in Part 108A from any uncrewed activity.

The total territory of the USA (contiguous 48 and Alaska) is 3,678,190 sq. miles, so at the end we have over 3.5 million square miles of territory that can be used for an initial deployment of Part 108A without disrupting commercial and GA aviation.

This oversimplified solution still leaves us with the conundrum of what to do with the thousands of private airports, grass strips and heliports scattered throughout the country, plus the issue of altitude restrictions.

Part 107, officially implemented in the summer of 2016, placed an altitude restriction of 400 ft to all flights with a few exceptions. This standard was copied around the world and converted to 120 meters in jurisdictions that use the metric system. Now the FAA has a real challenge in deciding what altitude would be appropriate to begin a gradual integration of piloted and remotely piloted aircraft (RPAs).

The 400 ft restriction is something that will have to be increased in Part 108 because a lot of routes and commercial applications will need to fly higher in order to achieve the efficiencies that made them possible in the first place.

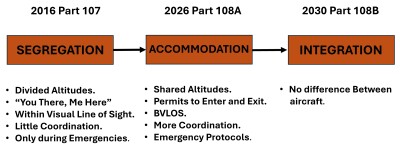

One way to achieve this gradual deployment will be to implement it in three steps, one already has been achieved, Segregation and the next two, Accommodation and Integration can be accomplished over the next five years.

The best example of this gradual deployment would be the delivery of a farm’s equipment spare part in Northern Montana versus the delivery of a pizza in New York City. The former is achievable today with drone under a Part 107 waiver and soon it will be possible under Part 108. The latter is still years away and in truth, we have no idea how it would be possible, so let us start with helping farmers in remote communities and kickstart the lengthy process of learning and accumulating data that would, eventually, give us the answers we need for a full integration of crewed and uncrewed aviation in the NAS.

At this point we have no idea if the FAA will publish the notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) this year or not, but all official and unofficial comments from officers from the federal agency seem to hint at a publication by the end of the year and a full implementation by Q1 2016.

The suggestion by Mr. Call in his early article plus my ‘aeronautical’ fine tuning of his proposal, are only attempts by private citizens at helping the FAA with this difficult step forward. We all hope they listen.

Comments