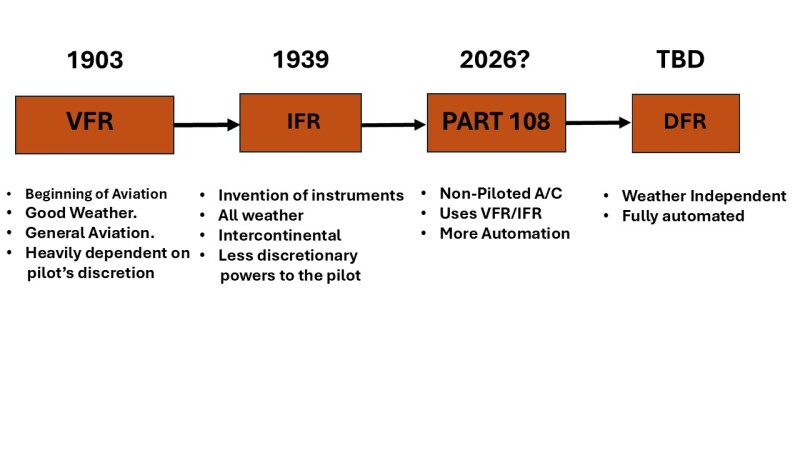

When the Wright Brothers first took to the skies over North Carolina on December 17, 1903, the only way to fly was to look at the ground, scrutinize the horizon and making sure there was enough speed and altitude to keep flying. Aviation quickly evolved, and for the next 100 years flights in the United States (and possibly most countries with aviation) were conducted under one of two ways: Visual Flight Rules (VFR) and Instrument Flight Rules (IFR). These modes have shaped everything from pilot training to air traffic control, defining how aircraft navigate, separate, and communicate. But now drones, autonomous systems, and advanced air mobility (AAM) platforms are entering the national airspace system (NAS), and the traditional VFR/IFR framework is showing its limits.

The aviation system is being asked to accommodate aircraft that do not carry pilots, do not rely on visual cues, do not fit neatly into the human‑centric logic of the past and are less dependent on weather. This is the context in which the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) proposed Part 108 and the NASA concept of Digital Flight Rules (DFR) have emerged, each addressing different layers of the same transformation.

Part 108, the FAA’s long‑awaited regulatory framework forBVLOS drone operations, is designed to unlock scalable uncrewed aviation under today’s rules. It introduces performance‑based requirements for surveillance, command and control, strategic deconfliction, and right‑of‑way responsibilities. It is a pragmatic attempt to bring order to a rapidly expanding segment of aviation without rewriting the entire operating rulebook.

DFR, by contrast, represents a more radical shift. Developed and articulated primarily by NASA, DFR is envisioned as a third operating mode that would sit alongside VFR and IFR, enabling autonomous and highly automated aircraft to operate using digital information, intent sharing, and automated separation. While the FAA has not formally proposed DFR, NASA’s work makes clear that the concept is not theoretical. It is a deliberate effort to define the operational future of the NAS.

Understanding the relationship between these two developments requires separating what is regulatory reality from what is strategic trajectory. Part 108 does not depend on DFR. Nothing in the FAA’s Part 108 Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) requires or even references a new operating mode. The rule is designed to function entirely within the existing VFR/IFR structure, using performance‑based standards to allow drones to operate safely without a pilot’s direct visual observation. Operators will still be responsible for separation, but they will do so through surveillance technologies, networked information, and procedural deconfliction rather than through a new regulatory category. In that sense, Part 108 is intentionally conservative. It expands what is possible without altering the fundamental architecture of flight as we know it today.

Yet the deeper story is that Part 108 is laying the groundwork for the world in which DFR would eventually make sense. NASA’s research into DFR begins with a simple observation: VFR and IFR were built for human pilots. They assume human perception, human decision‑making, and human‑centered communication with air traffic control. As the density of autonomous operations increases, whether from delivery drones, electric air taxis, or high‑altitude platforms, the human‑centric model becomes a bottleneck. NASA argues that a digital operating mode is necessary to enable automated self‑separation, machine‑readable constraints, and high‑density operations which do not overwhelm Air Traffic Control (ATC) or rely on visual cues that uncrewed aircraft cannot use.

In NASA’s framing, DFR would allow operators to assume full responsibility for separation using digital information services, intent sharing, and automation. Aircraft would communicate their trajectories, constraints, and performance capabilities in machine‑readable formats. In this new approach, separation would be maintained through cooperative automation rather than human observation or controller instructions. DFR would be compatible with all airspace classes, designed to coexist with VFR and IFR rather than replace them. It is, in essence, the operating system for a future NAS in which autonomy is the norm rather than the exception.

And this is where the eventual connection with Part 108 becomes meaningful. While Part 108 does not require DFR, it does require the very building blocks on which DFR depends. The FAA’s NPRM emphasizes information‑centric operations, operator‑provided surveillance, and performance‑based command and control (C2) requirements. It formalizes the idea that uncrewed aircraft can maintain separation through digital means rather than visual observation or ATC instructions. It introduces the concept of strategic deconfliction as a primary safety mechanism. These are not DFR references in the NPRM, but there are unmistakably steps toward the environment in which Digital Flight Rules could eventually be adopted.

NASA’s own documents make this relationship explicit. They describe DFR as requiring regulatory authorization and as being dependent on a digitally equipped NAS. They also emphasize backward compatibility, noting that DFR must integrate with existing operations and regulatory structures. In other words, DFR is not a replacement for Part 108; it is the logical successor to the ecosystem Part 108 is beginning to create. The FAA is not yet ready to adopt a new operating mode, but it is clearly preparing the infrastructure that would make such a mode feasible.

The FAA’s modernization efforts reinforce this trajectory. The agency’s work on Uncrewed Traffic Management (UTM), AAM integration, networked surveillance, and information‑centric airspace management all point toward a future in which digital information plays a central role in separation and situational awareness. Part 108 is one piece of that puzzle. It provides a regulatory foundation for BVLOS operations that rely on digital information rather than human observation. It begins to normalize the idea that separation can be maintained through automation and data rather than through traditional visual or controller‑based methods. It does not require DFR, but it undeniably moves the NAS closer to the world in which DFR becomes necessary.

The question, then, is not whether DFR is a prerequisite for Part 108. It is whether Part 108 is a prerequisite for the future that DFR envisions. The answer to that is yes. Part 108 is the bridge between the legacy operating modes and the digital‑native future. It allows uncrewed aircraft to scale under today’s rules while creating the operational, technological, and cultural conditions that will eventually make a new operating mode both viable and necessary.

DFR is not here yet, and the FAA has not committed to it, but the trajectory is unmistakable. The national airspace is moving toward a world in which digital information, automation, and cooperative separation define how aircraft will operate in the future. Part 108 is the first major regulatory stepping stone on that path.

Comments