Certain terms have been thrown around the drone industry so much that they begin to lose meaning. “Drone data” is obviously of critical importance, but how individual stakeholders and entire organizations define that term in the context of a drone program varies wildly. That’s not to say one definition is better than another but to highlight how so many different priorities and interpretations can cause someone to focus on the way data is captured rather than the value it provides.

The same loss of meaning has happened the term, “drone security”. It’s easy to talk about hardware and software defaults when it comes to “secure” data that is captured via drone, but what does that term mean to a given organization in the context of security protocols that are independent of a drone program? These sorts of questions are asked and answered in a new resource from Kittyhawk, “Factors, Tactics and Methods for Securing UAS Operations”.

The white paper details how and why security isn’t a checkbox but is instead an ongoing process that requires effort, resources and buy-in from all of the stakeholders involved. Those details are laid out in the white paper, but we were able to connect with Kittyhawk founder and CTO Joshua Ziering to further explore many of the insights in the white paper during a live webinar. An edited and condensed version of that conversation is below. You can also watch the unedited webinar or download the complete drone security whitepaper.

Jeremiah Karpowicz: Your new whitepaper, Factors, Tactics and Methods for Securing UAS Operations, is available for download right now. Before we get into the specifics of what's in the white paper, let’s pull back and figure out what we’re really talking about with something like “drone security”, because it can go in so many different ways and focus on so many different things. What's your baseline for that term in this white paper?

Joshua Ziering: Part of the thesis for this was being able to take a step back from all of the talk about security tactics because when any technology starts to mature, there starts to be different conversations around it.

Joshua Ziering: Part of the thesis for this was being able to take a step back from all of the talk about security tactics because when any technology starts to mature, there starts to be different conversations around it.

Let's look at a couple of technologies that kind of lend themselves as a corollary to what we're talking about today. A good one might be social media, but this has nothing to do with “like” buttons or retweets or anything like that. In the beginning, it was a free for all data grab. You could put up your pictures, tag your friends, or tag anyone you want. That had some not so fantastic effects when, for example, someone who wanted to hurt America's democracy could then use this technology in a weaponized fashion. And that was largely because that technology had become somewhat mature, but we weren't having the secondary follow up conversation around what’s going to happen with the data.

As another example, think about your security expectations with your smartphone. For the past couple years, I’ve wondered why “Words with Friends” needed to know my location. It wasn't until we started having those conversations about data security and privacy and maturity that other people have asked that same question. We were able to figure out that maybe we don't want all of these things to be happening, even though they can very easily always be happening from a technical perspective. And I think drones are much the same way.

When we think about drones, they exploded onto the scene. What is it? How do we know how it works? How are we going to be able to leverage this? It became very clear very quickly that these are tools and we're going to be bringing them to work. We need to treat them like any other very powerful tool. When used correctly, they're incredibly effective, but they're also extremely powerful. So let’s treat this technology with the respect that it deserves.

That's really where this whole security notion and conversation started. At Kittyhawk, we quickly saw that our customers were really looking to have a higher bar of security and be able to double down on all of the operations that they want to do with drones but in a secure fashion.

Jeremiah Karpowicz: The whitepaper uses the term “secure UAS operations” but how do you define that? How is that definition directly or indirectly incorporated into the concept of a security posture that is referenced?

Joshua Ziering: The way that I like to phrase it is that one drone can solve a lot of problems but many drones can create a lot of problems.

You can see that if you take away the word “drone”. If I told you, “Hey, would you like to bring high-quality cameras that are powered by flying Linux computers into your organization, with virtually no oversight?” That would be a problem to most organizations, and that's really what drones are. So we need to treat them with the respect they deserve and be cognizant of their unbelievable power.

As for the security posture, that is just this very baseline understanding of all the different types of security hygiene that you do. And I don't know why this is, but the security industry has adopted all of these kinds of very anatomical metaphors with hygiene and posture. It signals that security is not just one thing, it is a body of work. And that's maybe where all these anatomical metaphors come from, such that when you look at a security posture, it's not just any one part, because it's the entire picture. So, security posture is anything your organization is doing to mitigate risk and simultaneously derive benefits from the drone program.

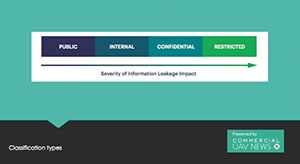

Jeremiah Karpowicz: Further exploring some of the concepts that the whitepaper spells out, I wanted to ask you about the four levels of data classification that the whitepaper defines, because I think it's really instructive. What kind of challenges have you seen organizations run into when they don't try to simplify how they categorize data in a similar manner? When they are perhaps using too many categories?

Jeremiah Karpowicz: Further exploring some of the concepts that the whitepaper spells out, I wanted to ask you about the four levels of data classification that the whitepaper defines, because I think it's really instructive. What kind of challenges have you seen organizations run into when they don't try to simplify how they categorize data in a similar manner? When they are perhaps using too many categories?

Joshua Ziering: Well, let’s rewind for a quick second for those of us who maybe are not data security nerds.

What we're looking at here is data classification. So you take all of the data in your organization and you make data buckets. These are just example buckets, so they don't have to be your buckets, but they are pretty good starting points. The idea is that if you can classify data in buckets, then you're able to better understand how much protection a specific set of data needs. That's what we're getting at.

One of the things that we're working on is to not make anything too complicated. I'm a big fan of keeping it simple. And with security, you have to keep it simple because even though you as the stakeholder might understand the impact of all 27 colors and classifications of data types, you have to remember that the rest of your team is just as important in implementing this correctly as you are.

If users are confused you’ll end up with a polarization of data where the silos are very big. As you get more nuanced, people are less willing to commit to the nuance. So keeping the classification simple is really important.

Jeremiah Karpowicz: There's no easy answer to this question, but I'll ask it anyway: who is it that makes the decisions about these four buckets or however many an enterprise organization might need? As you said, maybe it makes sense to have these four, but who’s making that decision and establishing this process?

Joshua Ziering: Like most things, I think it has to be a team effort. You need to get the stakeholders in the organization but also get them involved at the very start of this process of creating your drone program. You don’t want to create the drone program only to find out it doesn’t follow any of the established protocols. You want them involved from the start.

There are, in our experience, real gatekeepers to getting things done at scale with drones. If you can involve them very early on and say “hey, how do we classify these kinds of things? How can we work together to fit into your existing data classification structure?” things tend to move a lot faster and a lot smoother. Certainly, there are a million different ways to skin this cat, but you want to tell the right people that you want to approach the creation of a drone program in the right way so as to minimize the amount of trouble and headache. When you're inclusive in that way, it's much smoother moving forward.

Jeremiah Karpowicz: How should somebody go about actively or passively protecting themselves from the four threat metrics you’ve laid out, which are Time, People, Information and Money?

Jeremiah Karpowicz: How should somebody go about actively or passively protecting themselves from the four threat metrics you’ve laid out, which are Time, People, Information and Money?

Joshua Ziering: It's all about an assessment. If you look at all five of these entities, if there's nothing to steal, they won't be able to steal it. And that's a great thing.

When we think about data in the enterprise, every new piece of data you bring into the ecosystem is like bringing a new puppy into your house and training it. Every new piece of data that you add is something that your organization will be responsible for, for the foreseeable future, so you need to make sure it's taken care of. As long as that data is around, someone has to be the steward of it, just like someone has to be the steward for that puppy.

That also illustrates the distinctions between operational security versus informational security.

Jeremiah Karpowicz: Can you quickly outline the difference?

Joshua Ziering: Informational security is putting a good password on sensitive pictures in your system. Operational security is not taking them in the first place. And as you might be able to discern, I'm a fan of operational security, but these things do have to work in tandem. When possible, operational security has a much higher success rate because you can't steal it if it's not there.

Jeremiah Karpowicz: One of the things that jumped out to me in the report was the concept of letting data “run free”, and I wanted to ask you about what it means to draw the line between that kind of total freedom versus a security process that limits how people can do their jobs.

Joshua Ziering: Let's take the malicious side out of this. So say there's no spies or anything like that. Let's just say we don't have a data policy. So we don't classify anything, we just kind of use this data. The really interesting thing about drones pertains to what kind of data they print on everything they do, which means there are ramifications to this kind of policy, even when you aren’t dealing with data being snuck out of an organization in a metal briefcase.

Every picture you take with a drone has information about the drone, about the location and various other pieces of secondary metadata associated with that picture. If you're not cognizant of that data existing, you can find yourself sending that picture to someone with really, really specific pieces of information associated with it, which they may not know is intellectual property. Certain stakeholders can be very cognizant of this, but other people on a team might not be as aware or concerned about that sort of thing because they’re just trying to get their jobs done. That's really where you start to see the divergence.

I think most people inherently want to do their job, and they want to do a good job, and they want to do it quickly. And if you're lucky enough to have a team like that, you often don't want to slow down that process. So what happens is people get creative and you have these unintended side effects where a picture got forwarded to a personal email address and then forwarded back because they were trying to print it out. And the VPN wouldn’t let them print it out. These kinds of improvisational data management techniques are really bad for secure UAS programs.

It might hurt your productivity a little bit to make sure everyone is super by the book but it can end up being an easy decision.

Jeremiah Karpowicz: And that ties into another concept from your whitepaper that talks what it means to answer in the default. What does that mean in a practical sense?

Joshua Ziering: It’s really easy for people to go with the default and I’ll give you a good example of this.

When you sign up for a new app on your phone, the “please sign me up for the newsletter” will typically be automatically checked, and most people don’t uncheck it, because they go with the default. I know I've been guilty of this in the past, but let's not go to default.

If you do this as part of a drone program, what information is someone really going to get? It depends on the type of drone, but that could be your location data, or your mapping data, or your 3D model. It’s why you have to understand what data is being stored, as well as when and where. Setting up that kind of process is one of the good ways that you can make sure you're not following the default.

Even with all of that, what you should always remember is that nothing is truly secure. That is the baseline notion that we should always think about. There is nothing that is, “Secure”. Security is a metric of risk. If you think about airline crashes, the metric is 10 to the minus nine, so in United States, it would take about a billion hours of you sitting on a random airliner to be involved in a fatal plane crash. We should think about security in the same way, in the sense that it is this difficult to break into this system. It would take a million years of a well funded out adversary with lots of information to break into our system in this way. It's always a measure of risk.

Jeremiah Karpowicz: The white paper also touches on what it means to create and enable a security culture, but what does doing so look like in the short and long term?

Jeremiah Karpowicz: The white paper also touches on what it means to create and enable a security culture, but what does doing so look like in the short and long term?

Joshua Ziering: Creating a security culture is really about giving you the advantage of saying your team has been trained in this area. They're going to be able to identify when something's amiss. They're going to be cognizant of where they're sending data and also what data they're sending, although nothing's perfect. Creating a security culture is about allowing you to operate in a way that enables your team to scale.

If you're not thinking about this when your team is five or six people, going back in to set this up when it's 30 or people is a nightmare. So if you can start from day one, you can essentially create evangelists in your own organization that can transfer all of the information about data classification, best practices, speaking up if something's wrong, etc., to new team members that will also proliferate amongst themselves and the organization. So the amount of work that you have to do going forward is at very worst, the same, and hopefully, even less than it would be if you were trying to figure this out after the fact.

There's a number of different ways that you can think about this in the white paper; about what is a good practice for security culture and how you can get started even when your team is small, because that's really the time to do it.

You can watch the whole webinar to hear more about what Josh had to say regarding all these questions as well as some from the audience that pertained to UTM security, what makes Kittyhawk’s approach to this topic distinct, how he sees things with drone security taking shape over the next few years and much more.

The Factors, Tactics and Methods for Securing UAS Operations whitepaper is available now as a free download.

Comments