How the FAA’s Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) Notice of Proposed Rule Making (NPRM) reshapes costs, compliance, and opportunity—and why an “Uber for Drones” platform may be the practical bridge for thousands of small Part 107 and public safety operators

For decades, the promise of drones has hovered just beyond reach. While Part 107 of the Federal Aviation Regulations opened the door to commercial drone operations in 2016, its visual line of sight (VLOS) restriction has kept most missions small‑scale and local. The real transformation lies in beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) operations, the ability to fly drones over long distances without a pilot’s eyes on the aircraft.

The FAA’s proposed Part 108 (BVLOS) and companion Part 146 (Automated Data Service Providers - ADSP) represent far more than regulatory plumbing. They fundamentally redraw the boundaries of safety responsibility, airspace management at low altitudes, and the economics of operating beyond visual line of sight. Where Part 107 democratized the skies by transforming a slow, case-by-case approval regime into a repeatable on-ramp for commercial drone work, spawning thousands of small businesses and new service verticals, the 2025 BVLOS NPRM and its ADSP counterpart now seek to convert waiver-era experimentation into routine, scalable BVLOS operations.

This regulatory shift, while market-making, also increases the fixed and recurring costs of doing business. This presents a significant choice for small Part 107 operators, including sole proprietors, two-truck outfits, and community-level service providers, who are looking to scale their businesses with BVLOS operations. They have three options: invest heavily in their own infrastructure, outsource their needs, or join a compliance-first, marketplace-style platform that offers bundled services such as training, insurance, ADSP access, mission dispatch, and other core services. Such an integrated gig-economy solution could become the “Uber for Drones,” absorbing much of the compliance burden, spreading the cost, and emerging as a necessary lifeline for small commercial operators and public-safety programs facing both a capability ladder and a compliance cliff.

Part 107: The Democratization Moment and its Economic Footprint

What Part 107 Enabled. When Part 107 took effect on August 29, 2016, it replaced a slow, case‑by‑case Section 333 regime with a simple, repeatable on‑ramp: a remote pilot certificate and aircraft registration.1 That change lowered transaction costs to enter commercial operations and created a large installed base of pilots and aircraft that enabled recurring drone services (inspections, mapping, media, agriculture) commercially viable.

Scale and Economic Impact. FAA registration and industry studies show a substantial installed base and recurring commercial activity. Market research places U.S. drone services revenue in the low single‑digit billions annually, while broader integration studies estimate tens of billions of dollars in economic impact as drone use scales across infrastructure, agriculture, utilities, and public safety.2 3 4 5

Waivers as Growth Fuel. The FAA’s waiver and exemption process has been a critical growth lever in the U.S. drone economy. Since Part 107’s enactment the FAA has issued many waivers that let operators push boundaries, including night operations, operations over people, and controlled BVLOS instances.6 Those waivers were the bridge between the old visual line of sight (VLOS) world and the new BVLOS promise. They enabled pilots and small firms to build experience, revenue, and public and customer trust while the rulemaking matured.7

Operator Mix. The Part 107 economy is dominated by small businesses, sole proprietors, and micro‑firms serving local markets (construction, real estate, agriculture, inspections).8 Large vertically integrated players (e.g., Amazon, Wing, Zipline) exist and will continue to scale, but they represent a small share of operator counts. Policy and equipage choices that raise fixed costs therefore disproportionately burden small operators and favor deep‑pocket incumbents.

Public Safety Adoption. Public safety agencies have rapidly adopted UAS for first response, search and rescue, and incident assessment. DRONERESPONDERS’ mapping dashboard documents over 1,900 public‑safety UAS programs, many of which rely today on streamlined Certificate of Waiver/Authorization (CoW/COA) processes and Part 91 public aircraft pathways to perform lifesaving missions.9

Economic Role of Waivers. The FAA has issued thousands of waivers to Part 107 operators since Part 107’s inception; those waivers unlocked incremental revenue and capability for operators who otherwise could not perform higher‑margin missions.10 11 Conservatively, those waivers supported hundreds of millions, if not billions, of incremental service revenue by enabling repeatable, higher‑value work.12 13

The Promise. The BVLOS NPRM was designed to convert waiver‑based experimentation into a predictable, scalable regulatory framework. Key enabling features include:

- Broad BVLOS Use Case Support: The NPRM explicitly accommodates diverse mission profiles, including public safety, critical infrastructure, commercial delivery, and recreational BVLOS operations. This broad scope indicates that the framework is designed to be inclusive and future-proof. As a result, the rule will remain relevant as technology and market demands evolve, eliminating the need for the same exemption, waiver, and rulemaking processes currently applied to BVLOS operations.

- Streamlined Airworthiness via Industry Consensus Standards that accelerate innovation by allowing safe designs to reach the market faster while still meeting rigorous safety expectations.

- Two‑tiered authorization (permits and certificates) that create a growth path from limited BVLOS to full organizational certificates.

- Operator‑centric compliance (operations supervisors, flight coordinators, Safety Management Systems) that lets organizations centralize risk and oversight rather than tethering every flight to an individually certified pilot.

- Formal ADSP recognition (Part 146) to create a certified market for strategic deconfliction, conformance monitoring, and airspace services, essential for high‑volume BVLOS operations. This was also foundational to the FAA’s strategy to federate management of the low altitude economic airspace, while retaining overall authority over it.

These elements were intended to enable scale, create predictable approval pathways, and let operators rather than individual pilots carry the compliance burden.

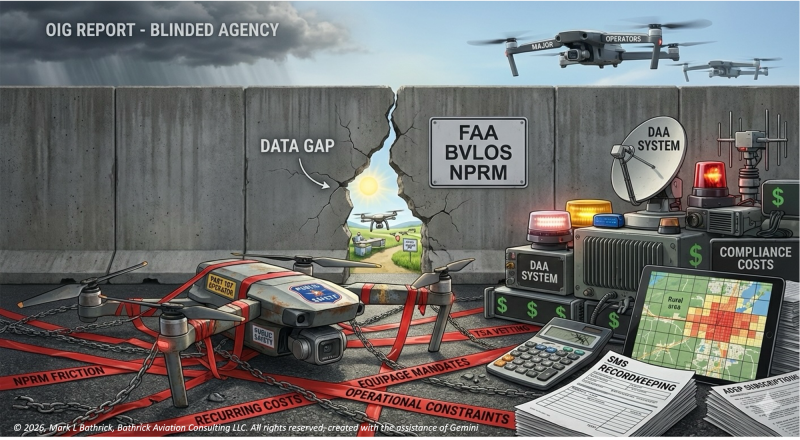

While the NPRM’s enabling features, such as streamlined airworthiness, broad BVLOS use case support, and formal recognition of ADSPs were designed to foster scalable, routine drone operations, there are many other elements of the NPRM that promise significant friction for existing operators and greater barriers to entry for new commercial drone business entrants. A critical foreshadowing of this comes from the Department of Transportation’s Office of Inspector General (OIG), whose June 2025 report sharply criticizes the FAA for unilaterally ceasing the collection of societal and economic benefits data in January 2023.14

This decision, as the OIG makes clear, effectively blinded the agency to the realities of the Part 107-enabled drone economy. By abandoning the very data streams that would have illuminated who the nation’s drone operators are, how they create value, and where regulatory friction helps or harms them, the FAA lost the ability to conduct a comprehensive, evidence-based assessment of BVLOS impacts. As a result, the NPRM reads as if it were crafted without a meaningful understanding that most commercial drone operators are small businesses or sole proprietors, not large, vertically integrated enterprises. This data gap likely contributed to an NPRM that tilts toward the operational models and resources of a small number of major operators, while imposing disproportionate compliance burdens, equipment mandates, certification pathways, and operational constraints on the thousands of small Part 107 operators who form the backbone of the U.S. drone industry.

In short, by halting the benefits analysis at the precise moment it was most needed, the FAA may have produced a BVLOS NPRM that structurally disadvantages the very innovators and small businesses that Part 107 was designed to empower. This sentiment that the BVLOS NPRM, if enacted as currently written would imperil the U.S. commercial and public safety drone sector was widely expressed in public comments to the Federal Register.15 16 17 18

Against this backdrop, it is essential to examine the specific elements of the NPRM that threaten to significantly increase the cost and complexity of operations for small commercial operators and public safety organizations.

1. Equipage Costs

Detect and Avoid (DAA) Systems: BVLOS drones must be equipped, where required, with advanced DAA systems or suitable alternatives. The sophistication of these systems varies by operational context and population density category:

- Lower-density/rural (Categories 1–2): Minimal mitigation; reliance on strategic deconfliction.

- Moderate-to-dense (Categories 3–5): High-reliability, real-time DAA systems mandatory, including ability to identify non-cooperative (non-ADS-B equipped) aircraft.

Anti-Collision and Position Lighting: All Part 108 aircraft require industry-compliant anti-collision lights for day and night, and position lights for night operations.

Command and Control (C2) and C2 Link Monitoring: Drones must have robust C2 systems, supporting remote operation with resilient, redundant communications, and C2 link monitoring. Operators must also maintain reliable backup and emergency return protocols.

2. Recurring ADSP/UTM Subscriptions

Strategic deconfliction and conformance monitoring will be delivered by certified ADSPs under Part 146. That creates ongoing subscription costs for every operator and mission, an operating expense that scales with flight volume and is not a one‑time capital purchase.

3. TSA Vetting and Onboarding Friction

The NPRM imports TSA‑style Security Threat Assessments (STAs) for key personnel (operations supervisors, flight coordinators), adding per‑person costs and onboarding time.

4. Training, Safety Management Systems, Maintenance, Repair, Aircraft Tracking, Recordkeeping, and Reporting

Certificates require full Safety Management Systems (SMS), recurrent training, and extensive recordkeeping (flight logs, maintenance, logging of life-limited or critical parts, battery state-of-health tracking, occurrence reporting, etc.). Small operators must either build these capabilities or outsource them, both add cost and complexity.

5. Population‑Density Mapping and Misaligned Constraints

The NPRM’s population category framework ties privileges to land‑use/population density. The use of static LandScan USA data for population risk categories has limitations, including:

- Does not reflect dynamic population surges (e.g., outdoor events, traffic jams)

- May underestimate/overestimate risks in certain timeframes or transient congestions. This limitation could result in unsafe operations or unjustified restrictions.

- Mapping artifacts pose a risk of categorizing low-altitude agricultural or private land operations into stricter categories, such as transitioning from Permit to Certificate requirements. This shift would necessitate significantly higher equipment, personnel, and monitoring requirements that may not align with the actual risk profiles of these operations. This is particularly challenging for farm spraying and other low-risk, low-altitude work.

6. Insurance, Cybersecurity, and Reporting.

New insurance expectations, cybersecurity policies, and mandatory occurrence reporting increase premiums and administrative overhead, further raising per‑mission costs.

7. Supply‑Chain and FCC/Federal Sourcing Impacts.

Recent FCC directives and NDAA/Blue UAS pressures on foreign‑made platforms increase replacement costs and create procurement uncertainty for operators who relied on low‑cost foreign platforms, forcing fleet transitions or higher capital outlays.19

While exemptions contained in the FCC’s January 7, 2026 update20 offer an immediate bridge, the hard "sunset cliff" on January 1, 2027, has left many industry leaders viewing the move as a precarious reprieve that fails to provide the long-term regulatory certainty required for major capital investment. This short-term window forces manufacturers to navigate a landscape of rolling deadlines and conditional approvals, perpetuating a climate of deep anxiety over whether domestic supply chains can scale before the clock runs out. Consequently, the industry remains in a defensive "wait-and-see" posture, fearing that these carve-outs are merely delaying an inevitable and disruptive supply chain shock rather than solving it.21 22 23

Net Effect. Estimates indicate attaining and sustaining Part 108 compliance could cost operators tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars in one-time/per aircraft and recurring costs. For many small operators the combined capital and recurring costs of equipage, ADSP subscriptions, SMS staffing, vetting, and insurance, along with the cost of time requirements to ensure regulatory compliance could exceed the incremental revenue from many BVLOS missions.24

While commercial drone operators and public safety agencies both navigate the same airspace and face many of the same regulatory challenges under the BVLOS NPRM, public safety organizations have distinct operational requirements and concerns. As DRONERESPONDERS pointed out in their public comments to the NPRM, public safety operators are not simply another category of Part 107 commercial drone users.25 They are mission‑critical, resource‑constrained, time‑sensitive, and risk‑managed government and civic responders whose operational realities cannot be governed by the same frameworks designed for commercial enterprises.

Public Safety Missions Are Life‑Critical, Time‑Sensitive, and Unpredictable

Respond to imminent threats to life every day—not “rare events.”

- Must launch immediately, often with no time for pre‑coordination, approvals, or complex administrative steps.

- Often require dynamic rerouting, manual control, and rapid tactical decision‑making in response to changing circumstances.

- Frequently occur in dense urban environments, where most emergencies happen.

Public Safety Agencies Operate With Limited Resources and Cannot Absorb Commercial‑Grade Regulatory Burdens

- Often have fewer than 25 aircraft

- Operate with no dedicated aviation department

- Constrained and often inflexible government funding precludes buying expensive DAA systems, licensed C2 links, or enterprise UTM subscriptions

- Staffing constraints prevents hiring dedicated personnel for complex recordkeeping and reporting requirements.

Public Safety Requires Broad, Flexible Areas of Operation—Not Small, Pre‑Defined Boxes

- Public safety and emergency response operations don’t honor constrained Landscan population category boundaries.

Public Safety Must Have Airspace Priority and the Ability to Operate Dynamically

- Like ambulances, fire trucks and police cruisers, public safety drones can’t “wait for green lights” or “no traffic” to respond.

Net Effect: As with current Part 107 commercial drone operators, Part 108 would impose substantial new costs, operational limitations, and administrative burdens on public safety agencies. While commercial operators might be compelled to invest heavily, outsource, or join compliance-focused platforms to remain viable, public safety organizations face the added risk of being unable to swiftly and flexibly launch life-critical missions, as required by their unique operational demands. Consequently, both communities, including small commercial operators and public safety agencies, could find themselves structurally disadvantaged, with the compliance and cost burdens threatening to undermine the very benefits that expanded BVLOS operations were intended to provide.

What does History Predict for the Final Version of Part 108 and Part 146?

Based on historical FAA rulemaking patterns, a final Part 108 and Part 146 rule is likely to retain the NPRM’s core regulatory architecture while selectively moderating the most operationally burdensome elements in response to public comment. Across recent UAS rulemakings—most notably Part 107 (2016), Operations Over People (2021), and Remote ID (2021), the FAA has demonstrated a consistent tendency to preserve the fundamental structure proposed in the NPRM (new rule parts, risk‑based frameworks, and performance‑based compliance models), even when faced with extensive stakeholder feedback.26

In each case, the final rule largely mirrored the NPRM’s intent and organization, with changes concentrated in implementation details, thresholds, timelines, and compliance pathways rather than wholesale redesign. The Remote ID rule provides the clearest precedent: despite tens of thousands of comments, the FAA maintained the requirement for remote identification but removed the network‑based component to address feasibility, cost, and privacy concerns—an example of targeted adjustment rather than structural retreat.27 28

This pattern suggests that Part 108’s permit‑and‑certificate framework and Part 146’s formalization of third‑party service providers (ADSPs) are highly likely to survive intact in the final rule.

Where alignment may soften is in the calibration of burden, phasing, and flexibility, particularly for small operators and public safety users, but not in the overall direction of travel. The FAA’s own rulemaking procedures under 14 CFR Part 11 allow substantive changes only when they remain within the scope of the NPRM or are preceded by a Supplemental NPRM, which historically signals major divergence.29 Absent such a supplemental notice, the agency typically addresses comment‑driven concerns through extended compliance dates, alternative means of compliance, exemptions, or scaled requirements rather than by abandoning the proposed framework.

Considering the extensive record of comments emphasizing cost, equipment, training, and administrative implications under Parts 108 and 146, the most likely outcome is a final rule that retains the NPRM’s performance-based BVLOS and UTM architecture but introduces transitional relief, clarified definitions, and narrower applicability for the most stringent provisions, similar to the FAA’s approach when finalizing Operations Over People and Remote ID. In short, history indicates high structural alignment with moderate requirement‑level adjustments: the final Part 108 and 146 rules will look recognizably like the NPRM, even if some of its sharpest edges are sanded down to smooth its implement-ability and enhance its political durability.

The Platform Solution: Why An “Uber for Drones” is the Practical Bridge

As history suggests, the final versions of Part 108 and Part 146 will likely retain the NPRM’s core regulatory architecture, with only moderate adjustments to ease the most burdensome requirements for small operators and public safety agencies. This means that while the fundamental shift toward performance-based BVLOS operations and formalized third-party service providers is almost certain, many small businesses and public safety organizations will face significant compliance and cost challenges stemming from the many new requirements contained in the NPRM.

Coupled with the complexity and uncertainty of the final Part 108 and Part 146 rule, the two recent bombshell Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Covered List announcements have added further uncertainty, confusion, and requirements for commercial drone operators and public safety drone programs to assess and adapt to.30 31

These changes collectively support the feasibility of a platform-based business model, allowing a central operator to manage compliance, scheduling, and risk for a distributed network of independent drone pilots. In this evolving landscape, an “Uber for Drones” offers a practical bridge, bundling the new regulatory demands into accessible, scalable services that can help small Part 107 operators and public safety drone programs transition successfully into the BVLOS era. This framework mirrors gig-economy platforms like Uber, enabling independent contractors to operate under a central compliance umbrella.

What a platform would provide. A first‑mover “Uber for Drones” platform can bundle the new fixed and recurring costs into a single service offering that spreads cost and complexity across many pilots and missions:

- Centralized compliance engine: SMS templates, automated recordkeeping, TSA STA integration, and audit support.

- Fleet and equipage management: FCC‑accepted, DAA‑capable aircraft leasing and maintenance scheduling.

- ADSP integration: Single‑contract access to strategic deconfliction and conformance monitoring.

- Insurance and cybersecurity: Platform‑wide policies and standardized cybersecurity baselines.

- Training and credentialing: Modular, role‑based training and recurrent checks aligned to permit/certificate tiers.

- Dispatch and marketplace: Job matching, dynamic scheduling that enforces duty/rest rules, and surge pricing for emergency response.

- Dual Part 107 and Part 108 support: By providing Part 107 pilots with support (e.g., manage FAA Remote Pilot Certificates, help with recurrent test reminders, offer knowledge base portals, and integrate upstream with flight planning and logging software, etc.) they capture future Part 108 customers and enable clients to easily operate in both VLOS and BVLOS worlds.

Why this helps small operators. Aggregation spreads fixed costs (vetting, ADSP subscriptions, SMS overhead) across many flights and pilots, lowering per‑mission cost and enabling small operators to compete on service rather than regulatory muscle. It also creates a clear upgrade path: Part 107 pilots can join as contractors, access training and equipment, and scale into BVLOS work without individually absorbing the full compliance burden.

Agriculture as a bellwether. The agricultural drone product and service market serves as a perfect example of an industry where an “Uber for Drones” could help it meet its potential.32 The ag drone market is projected to gro7w to $3.9 billion by 2031.33 Agricultural spraying and mapping are recurring, geographically distributed, and often low‑altitude, yet the NPRM’s mapping and C2 requirements could push many farm operators into expensive and demanding Permit or Certificate regimes.34

Companies like Farm‑i‑Tude (education,35 CropFlight logbook,36 137 support37) and American Drone Network (pre‑registered fleets, financing, pay‑by‑acre) already provide pieces of the compliance, training, and fleet puzzle.38 A partnership or integrated platform that combines Farm‑i‑Tude’s compliance and education stack with ADN’s fleet, financing, and uptime guarantees would create a turnkey offering for ag pilots and small applicators, exactly the kind of managed service that converts regulatory pain into a market opportunity.

How this could support Public Safety. An “Uber for Drones” platform could provide public safety agencies with centralized access to compliant fleets, streamlined mission dispatch, and integrated regulatory support, helping overcome the resource and operational constraints that often challenge these organizations. Unlike commercial operators, public safety programs require rapid, flexible deployment for life-critical missions, dynamic rerouting, and broad operational coverage, often without the luxury of pre-coordination or extensive administrative steps. To truly serve public safety, the platform would need to offer features such as priority airspace access, real-time tactical control, and tailored compliance workflows that accommodate unpredictable, high-stakes scenarios.

This approach parallels solutions like Axon’s cloud-based evidence management and dispatch systems, which aggregate technology, compliance, and operational support for law enforcement and emergency services. By bundling compliance, fleet management, and mission coordination into a single, scalable service, an “Uber for Drones” platform could empower public safety agencies to maintain readiness and effectiveness, even as regulatory demands grow more complex.

Conclusion

Part 108 and Part 146 are poised to revolutionize the economics of drone operations. These rules will establish the regulatory framework for routine BVLOS flights, but they also elevate the standards for equipment, security, and organizational capabilities. Consequently, many small Part 107 operators will face a pivotal decision in their expansion into routine BVLOS operations: invest heavily, outsource, or join a platform that simplifies compliance complexities. This choice marks a significant breakout moment for the gig economy.

A well-designed platform that integrates compliance, ADSP access, certified fleets, insurance, and marketplace dispatch can unlock BVLOS revenue for thousands of small operators while ensuring predictable and auditable safety for regulators and enterprise customers. The first entity to master the compliance economics and collaborate with domain experts in agriculture, public safety, and utilities will shape the practical contours of the BVLOS economy for years to come.

Comments