The FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 gave the FAA the flexibility to regulate all drones, but the recent demonstration performed by AirMap, Alphabet’s Wing, and Kittyhawk.io showcased what it could mean to see that authority make practical sense. The three companies worked together to create a remote identification (Remote ID) solution that Acting FAA Administration Dan Elwell has said that we need to move the industry forward.

The InterUSS Remote ID solution that AirMap, Wing, and Kittyhawk.io showed off in December of 2018 is open source and network-based over the InterUSS Platform™. Designed to find the right balance between privacy and transparency, their demonstration illustrated that a Remote ID solution for drones exists today for drone operations in networked areas, without the need for additional infrastructure or technology. Their demonstration was proof that implementation of a Remote ID solution is really not a question of technology, but one of collaboration and policy.

Ben Marcus

Ultimately, what makes Remote ID such a major topic of importance for the drone industry as a whole? In the absence of a Remote ID standard with everyone participating in the system, we’ve seen a lot of spurious reports about drones flying near airports. The fact is, we don't know if the things that those pilots saw were drones or not. With a Remote ID system and with LAANC, access to the airspace is easily attainable, and that allows us to know for certain whether or not a drone was somewhere it shouldn’t be.Solving this issue will allow the industry to continue to grow, and that’s why so many people are focused on it. In the absence of this regulation, there has been a lot of confusion about who is permitted and who isn't permitted to fly in various pieces of airspace, and a Remote ID solution will help sort all of that out. Is that issue of access and identification the reason the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 gave the agency the power to enable Remote ID in a major way? A couple years ago the FAA was essentially ready to allow for drone flights over people, but the Department of Justice pushed back on that, because while they granted that the FAA might have been able to determine that these operations were safe, the DOJ had a concern about the security of those operations. There was no way for the DOJ to identify the operators of those drones remotely. That regulation was delayed because of those concerns, and the rest of the FAA's regulatory timeline has been pushed back because of the absence of a Remote ID regulation and technology standard.We've had a bit of a gap in the ability of the FAA to regulate because of the exemption for model aircraft operators, and that has now been clarified with the 2018 Reauthorization Act. With a regulatory framework that applies to all aircraft, I think we can now assure safety of the airspace to advance the technology and the industry as a whole. We can now have a ubiquitous Remote ID rule and set of technologies to deliver that capability. I think we'll see a much more rapid unlocking of the airspace for more advanced drone missions like BVLOS, autonomy and ultimately passenger carrying because of it. You mentioned that the exemption for model aircraft operators has now been removed as a result of the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018, and there has been a lot of pushback about that, much of which comes down to modelers saying what they want to do in the airspace is inherently different than what a commercial operator wants to do. Is that a fair argument? I think it's certainly true that there are many different operations happening in the airspace. I grew up build and flying model aircraft myself, and I understand that's a unique type of operation. That said, there are countless unique types of operation that happen in the airspace. People fly hot air balloons, blimps, gliders, etc. There are lots of exciting things that people do in aviation as a whole.As a whole, modelers are very safety conscious, and there's a real safety culture within the model aircraft community. As these model aircraft operators have seen the influx of small, easy to fly, recreational drones that you can buy at an electronics shop, they too have become concerned that if this new category of drones is not properly regulated, it will actually give modelers a bad name. With decades of a strong safety culture, I think they too recognize the value of a regulatory framework that isn't burdensome and provides the right mechanism to ensure safety in the airspace. It’s good to hear you have that perspective, as one of the other arguments I’ve seen from the model community is around how these new rules will make it that much harder to get kids involved. But I imagine it’s really not an issue of it being harder or easier, just a case of it being a different process than the one you went through.I actually think it’s way easier to get into now.When I was growing up, I had to build everything from scratch, wood, servos, motors, etc. I also had to go to a model flying field, and getting out to one of those wasn't an easy trip. Now though, everything is electric, you can fly in a park, plus vehicles are smaller and ready to fly. The new regulations really don't get in the way of these types of operations.

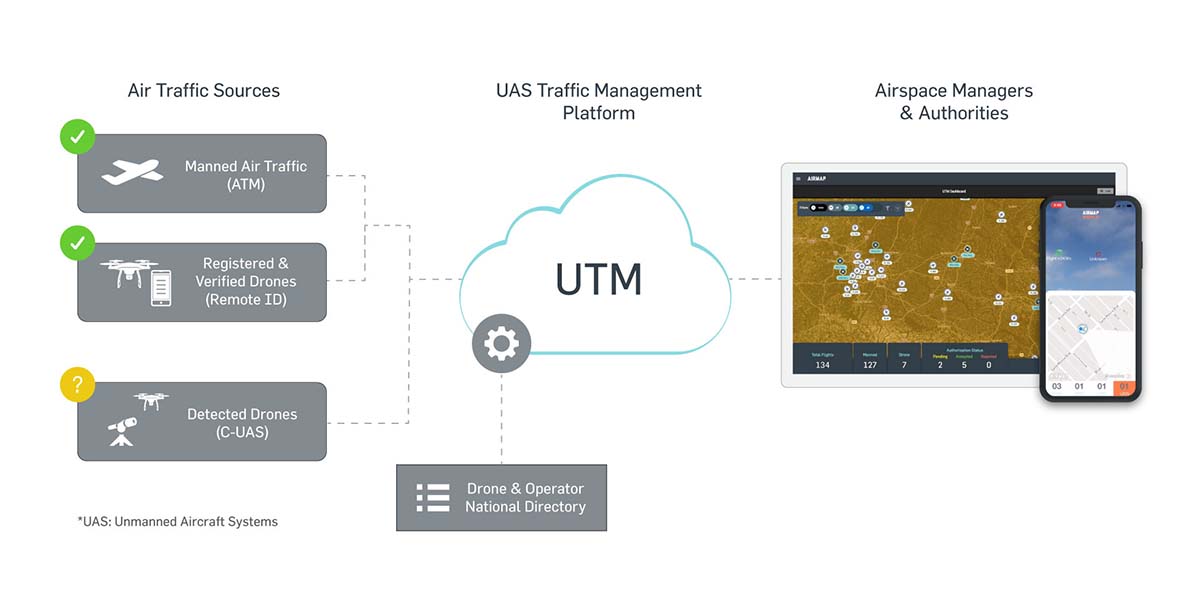

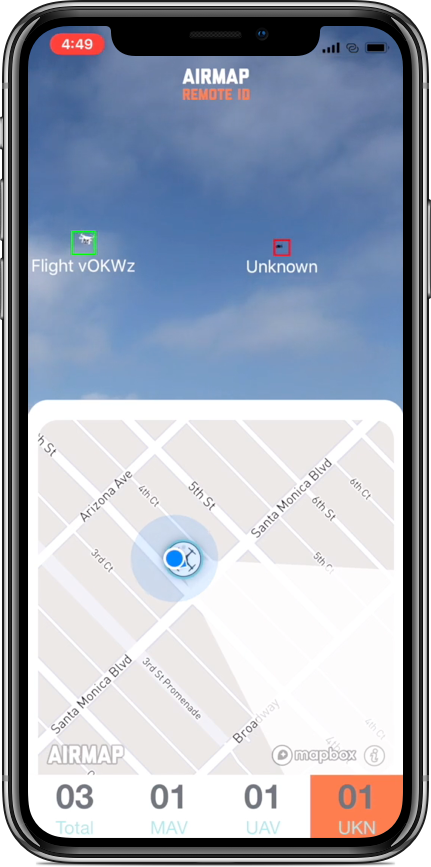

Ultimately, what makes Remote ID such a major topic of importance for the drone industry as a whole? In the absence of a Remote ID standard with everyone participating in the system, we’ve seen a lot of spurious reports about drones flying near airports. The fact is, we don't know if the things that those pilots saw were drones or not. With a Remote ID system and with LAANC, access to the airspace is easily attainable, and that allows us to know for certain whether or not a drone was somewhere it shouldn’t be.Solving this issue will allow the industry to continue to grow, and that’s why so many people are focused on it. In the absence of this regulation, there has been a lot of confusion about who is permitted and who isn't permitted to fly in various pieces of airspace, and a Remote ID solution will help sort all of that out. Is that issue of access and identification the reason the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 gave the agency the power to enable Remote ID in a major way? A couple years ago the FAA was essentially ready to allow for drone flights over people, but the Department of Justice pushed back on that, because while they granted that the FAA might have been able to determine that these operations were safe, the DOJ had a concern about the security of those operations. There was no way for the DOJ to identify the operators of those drones remotely. That regulation was delayed because of those concerns, and the rest of the FAA's regulatory timeline has been pushed back because of the absence of a Remote ID regulation and technology standard.We've had a bit of a gap in the ability of the FAA to regulate because of the exemption for model aircraft operators, and that has now been clarified with the 2018 Reauthorization Act. With a regulatory framework that applies to all aircraft, I think we can now assure safety of the airspace to advance the technology and the industry as a whole. We can now have a ubiquitous Remote ID rule and set of technologies to deliver that capability. I think we'll see a much more rapid unlocking of the airspace for more advanced drone missions like BVLOS, autonomy and ultimately passenger carrying because of it. You mentioned that the exemption for model aircraft operators has now been removed as a result of the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018, and there has been a lot of pushback about that, much of which comes down to modelers saying what they want to do in the airspace is inherently different than what a commercial operator wants to do. Is that a fair argument? I think it's certainly true that there are many different operations happening in the airspace. I grew up build and flying model aircraft myself, and I understand that's a unique type of operation. That said, there are countless unique types of operation that happen in the airspace. People fly hot air balloons, blimps, gliders, etc. There are lots of exciting things that people do in aviation as a whole.As a whole, modelers are very safety conscious, and there's a real safety culture within the model aircraft community. As these model aircraft operators have seen the influx of small, easy to fly, recreational drones that you can buy at an electronics shop, they too have become concerned that if this new category of drones is not properly regulated, it will actually give modelers a bad name. With decades of a strong safety culture, I think they too recognize the value of a regulatory framework that isn't burdensome and provides the right mechanism to ensure safety in the airspace. It’s good to hear you have that perspective, as one of the other arguments I’ve seen from the model community is around how these new rules will make it that much harder to get kids involved. But I imagine it’s really not an issue of it being harder or easier, just a case of it being a different process than the one you went through.I actually think it’s way easier to get into now.When I was growing up, I had to build everything from scratch, wood, servos, motors, etc. I also had to go to a model flying field, and getting out to one of those wasn't an easy trip. Now though, everything is electric, you can fly in a park, plus vehicles are smaller and ready to fly. The new regulations really don't get in the way of these types of operations.  Those new regulations will also allow for solutions like InterUSS to make sense in a way that it wouldn’t otherwise, so can you talk a little bit about this system and about the specific opportunities you think it will open up? Simply put, InterUSS Remote ID allows for multiple airspace services providers to communicate flight information of the operators using their services. It’s a solution that makes a lot of sense under these new regulations, but more importantly, it establishes that we can facilitate transparent and accountable UAS operations with network-based remote identification.The demonstration that we conducted in December with Wing and Kittyhawk.io had the three of each with flights that were using our systems, sharing the flight intent and trajectory information with one another. We used all of that for the purpose of demonstrating how Remote ID can work. With this system, a police officer standing on the ground can look into the sky and identify the operator of a drone that is flying by regardless of which USS that operator was using.This InterUSS Remote ID service is also useful for strategic deconfliction. If there’s a flight that is happening using the AirMap USS and other flights using Wing USS, those can be strategically deconflicted over the InterUSS Platform™.You'll continue to hear more about this through 2019. We have many more partners that are joining, and I think it's critical for the success of UTM but also for the drone industry more broadly. So when people talk about what Remote ID could or should look like, this is essentially the answer, isn’t it? Or it’s at least an answer to that question.It’s an important piece. There needs to be a protocol for the exchange of this data, and that's what InterUSS provides, but there also needs to be some interfaces for law enforcement or any other authorities to be able to identify who it is they see flying past. There are many other pieces to Remote ID. InterUSS is a critical component of the overall Remote ID solution. There was a lot of excitement when this demonstration was first announced, but there was also pushback from some who claimed InterUSS was too complex and unsecure. Are either of those claims valid?To be honest, I'm not sure why those criticisms exist. I think we’ve proven how simple this system can be, because we already demonstrated it by leveraging existing commercial cellular networks. Drones in this system will not need to have a modem onboard. I've seen people say they need one, but it's not the case. We can use the existing smartphones or tablets that many people have on them.We’re not sharing information in a different way than we share all kinds of sensitive information over the Internet every day. Critical information is exchanged all the time over the Internet, and it can be done very securely. We've learned best practices for transmitting sensitive data across the Internet. We’re storing and sharing information that isn’t getting intercepted. That's as opposed to local broadcast, which calls attention to itself in a way that the InterUSS solution does not.Is there a role for local broadcast? Absolutely. I'm emphatic about that. Sometimes you don't have an Internet connection or an Internet-connected device. There needs to be a local broadcast, and if a vehicle is broadcasting its position locally because there's no Internet connection there, but it got picked up by a receiver that does have an internet connection, then information should be exchanged through the InterUSS protocol so that information can be shared with others that are a part of the network and have a right and a need to have this info. It all works together is the bottom line. And what role should regulation play in how all of that will need to work together?There are all kinds of policy measures that we can take to clearly specify what type of data should be shared and what shouldn't be shared. Different actors in the system should have access to more data than others. It's not necessary that every member of the public that happens to have a receiver can listen in on the communication like would happen in a broadcast scenario. Law enforcement should have a set of privileges that are broader than a member of the public. It might be that if I see a drone fly by my window as a member of the public, I can easily get some information about that operation. But if I'm a law enforcement official, I should be able to potentially identify the purpose of the operator and who the operator is, etc. Those things can be defined by policy and then built into the platform so that only the right people are getting the right info. Beyond what could and will take shape with InterUSS and Remote ID in 2019, what are you looking forward to seeing develop and take shape this year?We’re seeing huge leaps in the number of companies that are accessing drones for enterprise operations, in areas such as logistics, transport, aviation and the supply chain among other verticals. One driver of transformation will be mounting pressure from competitors using similar solutions for their operations. In the coming years, drones will become an integral part of many business models.As technology advances, we’ll see drones that can fly farther carrying higher payloads, and into places previously thought impossible. Advanced commercial opportunities overwhelmingly require something more than what today’s basic rules can enable. This trend has been growing in recent years but will be a front and center issue across nearly every country with drone regulations over the course of 2019.Another promising step in the drone economy transformation is the progress being seen in establishing self-sustaining UTM systems globally, with airports and air navigation service providers already integrating Unmanned Traffic Management (UTM) technologies into existing ATM infrastructure. AirMap is currently deploying our UTM Platform across Europe, in countries such as Switzerland and the Czech Republic. Expect airspace management systems for unmanned aircraft to flourish in the near future, with UTM being widespread by 2020. To find out what Ben has to say about the creation of UTM and U-space ecosystems in the United States and Europe, what role AirMap is playing in the creation of these systems, click here.

Those new regulations will also allow for solutions like InterUSS to make sense in a way that it wouldn’t otherwise, so can you talk a little bit about this system and about the specific opportunities you think it will open up? Simply put, InterUSS Remote ID allows for multiple airspace services providers to communicate flight information of the operators using their services. It’s a solution that makes a lot of sense under these new regulations, but more importantly, it establishes that we can facilitate transparent and accountable UAS operations with network-based remote identification.The demonstration that we conducted in December with Wing and Kittyhawk.io had the three of each with flights that were using our systems, sharing the flight intent and trajectory information with one another. We used all of that for the purpose of demonstrating how Remote ID can work. With this system, a police officer standing on the ground can look into the sky and identify the operator of a drone that is flying by regardless of which USS that operator was using.This InterUSS Remote ID service is also useful for strategic deconfliction. If there’s a flight that is happening using the AirMap USS and other flights using Wing USS, those can be strategically deconflicted over the InterUSS Platform™.You'll continue to hear more about this through 2019. We have many more partners that are joining, and I think it's critical for the success of UTM but also for the drone industry more broadly. So when people talk about what Remote ID could or should look like, this is essentially the answer, isn’t it? Or it’s at least an answer to that question.It’s an important piece. There needs to be a protocol for the exchange of this data, and that's what InterUSS provides, but there also needs to be some interfaces for law enforcement or any other authorities to be able to identify who it is they see flying past. There are many other pieces to Remote ID. InterUSS is a critical component of the overall Remote ID solution. There was a lot of excitement when this demonstration was first announced, but there was also pushback from some who claimed InterUSS was too complex and unsecure. Are either of those claims valid?To be honest, I'm not sure why those criticisms exist. I think we’ve proven how simple this system can be, because we already demonstrated it by leveraging existing commercial cellular networks. Drones in this system will not need to have a modem onboard. I've seen people say they need one, but it's not the case. We can use the existing smartphones or tablets that many people have on them.We’re not sharing information in a different way than we share all kinds of sensitive information over the Internet every day. Critical information is exchanged all the time over the Internet, and it can be done very securely. We've learned best practices for transmitting sensitive data across the Internet. We’re storing and sharing information that isn’t getting intercepted. That's as opposed to local broadcast, which calls attention to itself in a way that the InterUSS solution does not.Is there a role for local broadcast? Absolutely. I'm emphatic about that. Sometimes you don't have an Internet connection or an Internet-connected device. There needs to be a local broadcast, and if a vehicle is broadcasting its position locally because there's no Internet connection there, but it got picked up by a receiver that does have an internet connection, then information should be exchanged through the InterUSS protocol so that information can be shared with others that are a part of the network and have a right and a need to have this info. It all works together is the bottom line. And what role should regulation play in how all of that will need to work together?There are all kinds of policy measures that we can take to clearly specify what type of data should be shared and what shouldn't be shared. Different actors in the system should have access to more data than others. It's not necessary that every member of the public that happens to have a receiver can listen in on the communication like would happen in a broadcast scenario. Law enforcement should have a set of privileges that are broader than a member of the public. It might be that if I see a drone fly by my window as a member of the public, I can easily get some information about that operation. But if I'm a law enforcement official, I should be able to potentially identify the purpose of the operator and who the operator is, etc. Those things can be defined by policy and then built into the platform so that only the right people are getting the right info. Beyond what could and will take shape with InterUSS and Remote ID in 2019, what are you looking forward to seeing develop and take shape this year?We’re seeing huge leaps in the number of companies that are accessing drones for enterprise operations, in areas such as logistics, transport, aviation and the supply chain among other verticals. One driver of transformation will be mounting pressure from competitors using similar solutions for their operations. In the coming years, drones will become an integral part of many business models.As technology advances, we’ll see drones that can fly farther carrying higher payloads, and into places previously thought impossible. Advanced commercial opportunities overwhelmingly require something more than what today’s basic rules can enable. This trend has been growing in recent years but will be a front and center issue across nearly every country with drone regulations over the course of 2019.Another promising step in the drone economy transformation is the progress being seen in establishing self-sustaining UTM systems globally, with airports and air navigation service providers already integrating Unmanned Traffic Management (UTM) technologies into existing ATM infrastructure. AirMap is currently deploying our UTM Platform across Europe, in countries such as Switzerland and the Czech Republic. Expect airspace management systems for unmanned aircraft to flourish in the near future, with UTM being widespread by 2020. To find out what Ben has to say about the creation of UTM and U-space ecosystems in the United States and Europe, what role AirMap is playing in the creation of these systems, click here.

Comments