An Undeclared National Emergency

Wildfires in the United States are no longer seasonal events; they have become a year-round national emergency.1 Over the past three decades, the average annual acreage burned has more than doubled, from 3.3 million acres in the 1990s to over 7 million acres today.2 The economic toll is staggering: the U.S. Department of Commerce’s National Institute of Standards and Technology estimates annualized wildfire losses between $63.5 billion and $285 billion3, while the 2018 California wildfires alone caused $150 billion in damages.4 More recently, the L.A. wildfires resulted in an estimated $28 billion to $53.8 billion in total property losses.5 Beyond property loss, wildfire smoke—laden with PM2.5 particulates—has been linked to increased respiratory illness, cardiovascular disease, and even cancer.6 7

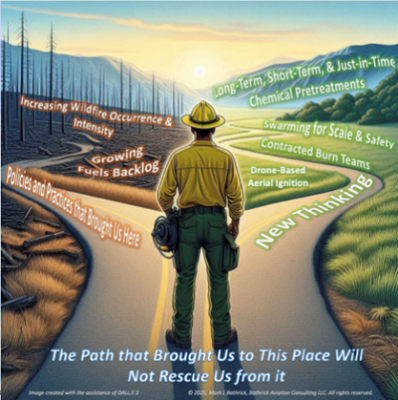

In my previous Commercial UAV News article, we highlighted and explored the reasons behind and potential solutions for the significant voids in aerial wildfire response to which we have turned a blind eye for nearly a century. In this installment, we investigate another often overlooked aspect of wildland fire management that has a profound impact on our ability to meet our current and future wildfire challenges. We will examine how decades of entrenched thinking and policy inertia in hazardous fuels management and treatment have put us at a significant disadvantage, like the significant gaps in aerial firefighting coverage. This has led us to a point where we are losing the battle against the single most controllable factor in wildfire occurrence and behavior—fuel.

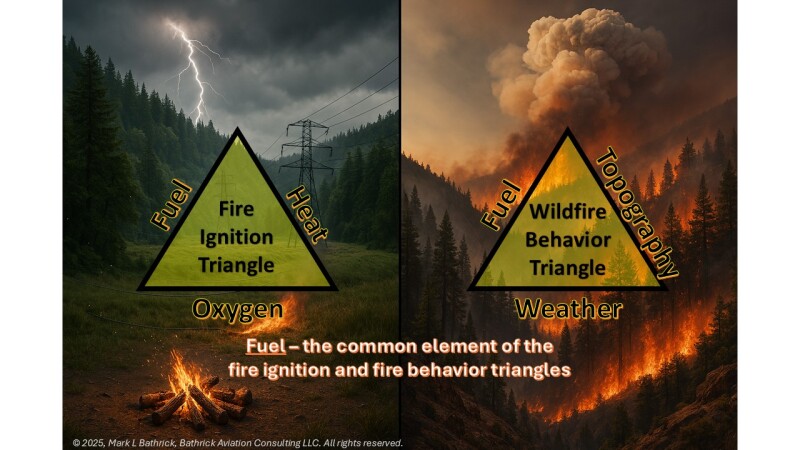

Fuel: The Common Denominator in Wildfire Occurrence and Behavior

Both the fire triangle (fuel, heat, oxygen) and the wildfire behavior triangle (fuels, weather, topography) share one element humans can directly control: fuel.8 Hazardous fuels, such as dense underbrush, small-diameter trees, deadfall, and slash, are the tinder that ignites a spark and transforms it into a catastrophic wildfire. Humans have recognized the crucial role of fuel in wildfire occurrence and intensity for millennia. Historically, beneficial fire practices, like controlled cultural burning, helped maintain healthy landscapes by reducing hazardous fuel levels and mitigating the risk of catastrophic blazes.

Where Do We Find Ourselves Today?

Our ancestors frequently used “good fire” to actively control hazardous fuel loading. However, the 20th century witnessed a paradigm shift towards practices that facilitated the rapid accumulation of fuels. These included:

- Suppression Bias - The U.S. bias toward wildfire suppression emerged in the early 20th century, fueled by catastrophic fire events, such as the 1910 “Big Burn” in the Northern Rockies, public fear, and a prevailing belief that all fires were detrimental to forests, communities, and economic resources. Federal policy, exemplified by the Forest Service’s “10 a.m. policy,” institutionalized rapid, complete suppression as the default response. This approach, reinforced by increased firefighting capacity, mechanization, and postwar infrastructure, protected timber, property, and lives in the short term. However, it disrupted natural fire regimes, allowing flammable vegetation to accumulate to historically unprecedented levels. 9 10

- Agency Funding, Structure, and Culture – As the bias toward wildfire suppression gained momentum, federal agency funding conformed to this new reality. For instance, in fiscal year 2024, the combined funding levels for Preparedness and Suppression (including the Wildfire Adjustment) accounts amounted to $4.4 billion, while the combined funding for Hazardous Fuels was only $271 million, representing a staggering 92 percent reduction compared to the Preparedness and Suppression funding levels.11 Wildfire agency organizational structures and career opportunities also aligned to the new “suppression is king” approach, further driving fuels management to a subsidiary role. A manifestation of this is the fact that prescribed burning is considered a collateral duty within the federal wildfire community.12 Agency cultural attitudes toward prescribed burning have also been affected by fears of personal liability, particularly following the arrest of a U.S. Forest Service (USFS) “burn boss” after the prescribed burn he was managing unintentionally sparked a separate blaze that consumed 18 acres of private land.13

- Public Acceptance of Prescribed Burns - Public resistance to prescribed burns in the U.S. stems from a mix of safety, health, and trust concerns, despite strong scientific evidence demonstrating their effectiveness in reducing long-term wildfire risk. Many communities harbor apprehensions that prescribed fires can escape containment and become destructive wildfires—a fear reinforced by high-profile incidents such as the 2022 Hermits Peak/Calf Canyon Fire in New Mexico, which began as a USFS prescribed burn and went on to destroy hundreds of homes,14 and the 2022 Las Dispensas prescribed fire escape, also in New Mexico, which merged with other fires to become part of the same disaster. Health concerns are another major driver of opposition: prescribed burns release fine particulate matter (PM2.5) linked to respiratory and cardiovascular problems, and residents often object to the smoky conditions they create, especially in vulnerable populations. While research shows that prescribed burns can reduce the severity of future wildfires by an average of 16 percent and net smoke pollution by 14 percent,15 public perception remains shaped by visible smoke, past accidents, and the lingering influence of 20th-century fire suppression messaging.

- Competing Land Management Priorities – Federal lands, comprising roughly 70 percent of burned acreage, are managed by various agencies. Consequently, it is common for multiple agencies, bureaus, and offices, often within the same department, to have overlapping and competing equities in the activities conducted on those lands. This can stall or derail planned hazardous fuel treatment projects. States are faced with similar challenges on the lands they manage. While fuels and wildfires don’t disregard the patchwork of federal, state, and private lands that often exist in wildfire-prone areas, land managers are compelled to navigate these challenges in developing and executing fuel management and treatment plans.

- Regulatory Challenges – Hazardous fuels reduction projects have historically faced challenges under the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA). Permitting processes consider project risks as well as potential air and water quality impacts.

- Reduced Logging and Inadequate Post-Harvest Management – Reduced logging over recent decades, driven by shifts in forest policy, environmental protections, and market changes, has contributed to the accumulation of hazardous wildfire fuels in many U.S. forests. Without active management, dense stands of small-diameter trees, ladder fuels, and dead woody debris can build up, increasing the likelihood of high-severity fires. Compounding the problem, if logged areas are not properly followed up with site preparation, replanting, or fuel maintenance often experience rapid colonization by fine fuels such as grasses, shrubs, and slash, as well as highly flammable invasive species like cheatgrass.16 These lighter fuels dry quickly, ignite easily, and can carry flames rapidly into remaining tree crowns, creating conditions for severe fire behavior.17 Research shows that poorly managed post-logging landscapes can, paradoxically, burn more intensely than unlogged forests.

- Growth in Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) “Fuel” - Over the past few decades, rapid growth in the wildland–urban interface (WUI) has placed more homes and infrastructure directly adjacent to fire-prone landscapes, effectively adding concentrated “human-instituted fuel” to areas already loaded with natural vegetation.18 Not only does this proximity increase the risk of any ignition, but it also restricts the use of prescribed fire and other fuel treatments. Residents often hesitate to support burns near their properties due to safety and smoke concerns, which allows hazardous fuels to accumulate unchecked. 19

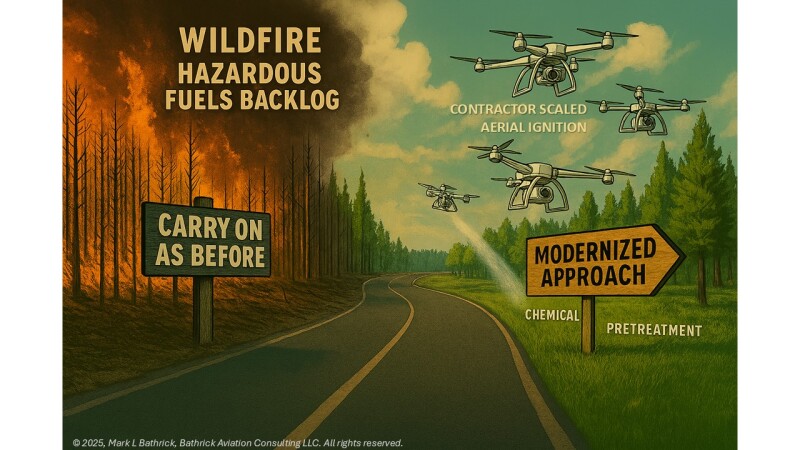

- Innovation Stagnation - Despite significant changes in the size and scope of the challenge and the availability of technology, the approach to mitigating the risks of hazardous fuels has remained largely unchanged for decades. Consequently, the traditional tools and techniques used to manage hazardous fuel treatments are increasingly inadequate to meet the evolving demands. While various factors, such as mission focus, funding, organizational structure, and culture, have contributed to this stagnation, the key to overcoming it lies in recognizing that the hazardous fuels treatment approaches that led to a substantial and growing backlog of over 20 years will not rescue us from it.

How Can Drones Help Us Modernize Our Response to the Growing Wildfire Fuels Backlog Crisis?

Drone-Based Aerial Ignition – An American Invention

Drone-based aerial ignition for prescribed burns was first developed and operationalized in the United States in the mid‑2010s, with early prototypes emerging from collaborations between the University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s Nebraska Intelligent MoBile Unmanned Systems (NIMBUS) Lab and the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) Office of Aviation Services (OAS).23 The breakthrough came with the IGNIS system, created by the Lincoln, Nebraska–based company Drone Amplified, which was publicly demonstrated in 2016 and began being used operationally by U.S. land management agencies shortly thereafter.24 25 This innovation allowed unmanned aircraft to drop small incendiary spheres (similar to those used in helicopter-based ignition) with precision, enabling safer and more efficient prescribed burns in difficult terrain.26 27

A 2020 USDA information paper found that drone-based aerial ignition saved $14,000/day over the traditional helicopter-borne aerial ignition.28 Helicopter-borne aerial ignition is also historically hazardous, with multiple mishaps and fatalities recorded over the years and as recent as 2019.29 30 Used in combination with sophisticated mapping software and leveraging onboard infrared sensors to monitor the ongoing progress of the burn, drone-based aerial ignition has been employed to safely burn large areas (100K acres) that are subject to complex land ownership challenges.31 In 2024, aerial ignition drones helped USFS burn 189,000 acres to reduce fuel loads.32 Aerial ignition drones have also enabled the first nighttime aerial support for burnout operations during active wildfires.33 34 35 36 While drone-based aerial ignition offers significant opportunities to safely and effectively scale prescribed burning as part of a comprehensive initiative to address the large and growing fuels backlog, organizational and cultural barriers continue to present barriers.

Swarming to Promote Speed and Safety

This traditional, time and labor-intensive approach to prescribed burning is also fundamentally linked to the risk of fires escaping containment. One of the persistent operational risks in prescribed fire is the potential for a burn to lose containment and transition into a wildfire when weather conditions—particularly wind speed or direction—shift unexpectedly.37 38 This risk grows the longer it takes to ignite and complete the burn, as extended ignition windows increase the exposure to changing atmospheric conditions and the possibility of spot fires or flare ups.39 A promising mitigation strategy is to shorten the total burn duration by increasing the number of simultaneous ignition points, creating a mosaic of small, adjacent fires that rapidly consume their immediate fuel and self-extinguish as they meet the blackened areas of neighboring ignitions.40

This “fast in, fast out” ignition pattern has long been recognized in prescribed fire science as a way to reduce residence time, limit smoke impacts, and minimize the window for adverse weather to intervene. The emerging capability of drone swarms, already proven in complex, precisely choreographed light shows involving hundreds or even thousands of aircraft under the control of a single operator 41 42 offers a pathway to apply this principle at unprecedented scale. By equipping each aerial ignition drone with onboard infrared sensors for real-time fire behavior monitoring, agencies can ignite large, complex burn units in a fraction of the time required by current ground, helicopter-borne, or single drone methods. This is complemented by integrating these drones with autonomous ground-based ignition platforms, such as those developed by Burnbot. This integrated swarm and ground approach could not only accelerate fuel reduction treatments but also enhance safety, reduce costs, and improve public confidence in prescribed fire as a proactive wildfire mitigation tool.

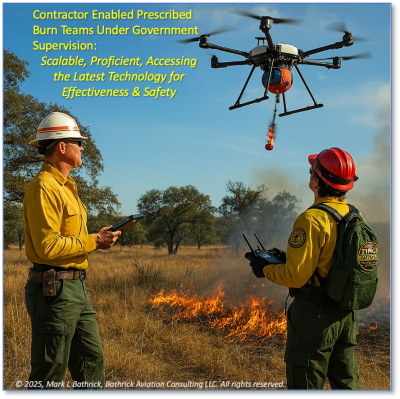

Contracting Prescribed Burning for Scale, Proficiency, Efficiency, and Alignment with Proven Practices

For decades, roughly 95 percent of the aircraft used in federal and state wildland firefighting have been supplied by commercial contract vendors, operating under the close supervision and tactical direction of government personnel.43 This contractor-centric model has proven to be a highly effective, efficient, and safe way to surge aerial firefighting capacity to meet wildfire demands, with government officials retaining the inherently governmental role of deciding where, when, and how to deploy these resources on federal fires, while empowering contractors to execute the missions. In contrast, prescribed burns have traditionally been conducted solely by government employees, often as a collateral duty alongside other primary responsibilities. This staffing model has constrained the amount of burning possible within the narrow seasonal windows and limited the proficiency of collateral duty burn bosses and crews. It is also influenced by fluctuations in federal employment levels.44

Further, in recent years, several prescribed fires managed by government burn bosses and executed by government crews have escaped control and evolved into damaging wildfires,45 46 47 48 incidents that may be partly attributable to the limited practice and operational repetition inherent in collateral duty assignments — and which have fueled public distrust of government-led prescribed burning. Although the U.S. Forest Service updated its agreements in December 2022 to expand the use of contracted resources for prescribed fire projects49 and reiterated this in its June 2023 National Prescribed Fire Resource Mobilization Strategy,50 the actual use of contracted crews for scaling prescribed burns remains rare.51 Building on the GAO’s June 2024 recommendations for strengthening the prescribed fire program and adhering to the proven aerial firefighting model, agencies could deploy contracted prescribed burn teams. These teams would be equipped with modern drone-based aerial ignition systems and supported by digital and AI-enabled weather forecasting, observation, and planning tools. They would be trained, qualified, and overseen by government officials. By deploying these teams, agencies could expand their capacity, enhance their proficiency, and free government personnel to focus on core missions.

Modernizing Our Thinking and Options for Hazardous Fuels Treatment

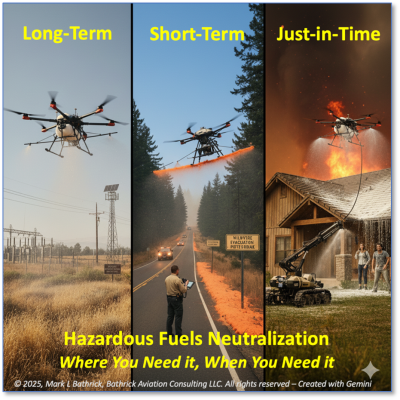

Given the reality that the United States faces a 20‑year hazardous fuels treatment backlog that far outpaces available funding, staffing, and public acceptance, relying solely on fuel “removal” or “elimination” will not close the gap. We must broaden our approach to include hazardous fuels neutralization—temporarily rendering fuels ineffective or harmless—guided by increasingly sophisticated pre‑year and in‑season dynamic wildfire risk assessments that integrate weather, drought, vegetation, and soil moisture, human activity, infrastructure vulnerability, and terrain data.

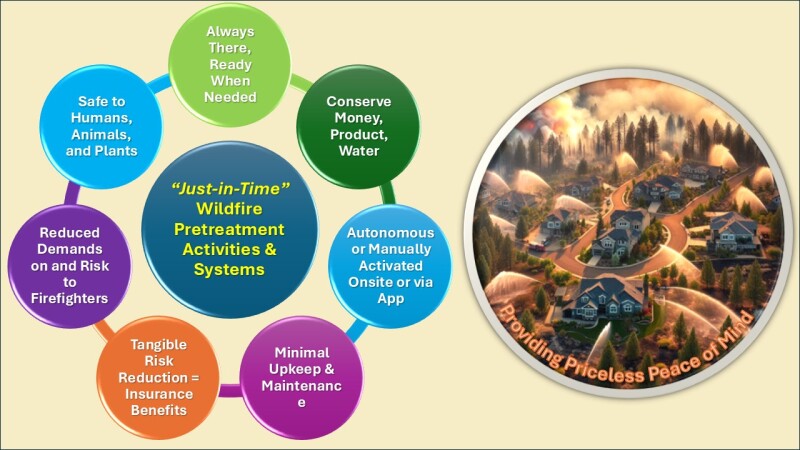

Using non‑toxic, government‑approved pretreatment products,52 53 54 55 applied from ground vehicles, backpack rigs, and drones,56 57fuels can be neutralized for the long term (e.g., protecting critical infrastructure for an entire fire season or more), the short term (e.g., safeguarding evacuation routes during elevated fire danger), or “just‑in‑time” (e.g., defending assets in the immediate path of an approaching wildfire). These just‑in‑time systems—always in place, low‑maintenance, and activatable manually or autonomously—offer tangible risk reduction for property owners and insurers, conserve resources, and reduce firefighter exposure. This is not theoretical: Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) has successfully deployed Komodo’s Phantom‑Blue pretreatment to protect hundreds of power poles ahead of wildfire spread, demonstrating the viability of rapid, targeted neutralization as a last line of defense.58 59 60

Drones hold enormous potential to extend the reach of hazardous fuels neutralization far beyond what is possible with traditional trucks, hoses, or even backpack sprayers. Modern heavy‑lift and terrain‑adaptive spray drones—many adapted from the rapidly growing agricultural spraying sector—can easily access rugged, roadless, or otherwise inaccessible areas, delivering precise applications over steep slopes, dense vegetation, or remote infrastructure corridors.61 62

In agriculture and invasive species management, drones have already proven their ability to cover large acreages quickly, with some models capable of carrying significant payloads and operating autonomously over uneven terrain.63 The payload and the beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) flight capability of drones promises to dramatically increase when the recently released BVLOS notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) is finalized,64 while programs like the SourceAmerica Mentor-Protégé Program open the doors to including wounded warriors and service-disabled veterans in meaningful technology employment in drone operations.65 66 67

These drone capabilities can be applied to wildfire fuel neutralization, enabling efficient pretreatment of critical infrastructure, evacuation routes, and other high‑risk areas identified through dynamic risk assessments. By leveraging the precision, speed, and accessibility of drone spraying technology, agencies can deploy long‑term, short‑term, or just‑in‑time neutralization treatments exactly where they are needed most—without the logistical constraints of ground‑based equipment.

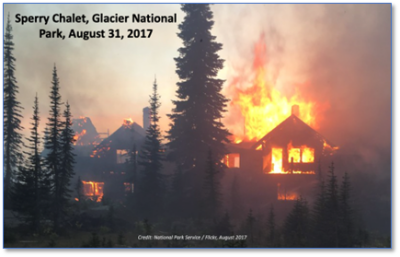

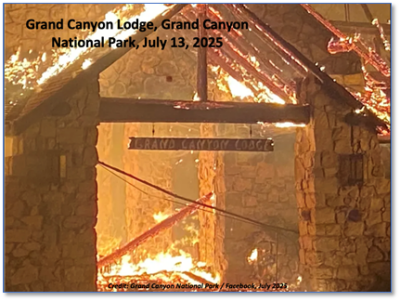

To fully realize the potential of fuels neutralization, the interagency wildland fire community must overcome two entrenched cultural barriers. First, despite federal approval, the USFS and DOI have historically used chemical pretreatments negligibly, reflecting a bias toward aerial fire retardants deployed only during active suppression. This is underscored by the recent USFS award of a nearly $1 billion, five‑year aerial retardant contract to a single vendor,68 continuing a decades‑long procurement pattern. Second, this bias has left agencies unprepared to defend high‑value, irreplaceable assets—such as the Sperry Chalet in Glacier National Park,69 70 Yosemite’s historic structures,71 and most recently, the historic Grand Canyon Lodge and other North Rim facilities72—with ground‑applied pretreatments before wildfire arrival, resulting in millions in losses and costly rebuilds.

While federal wildland fire agencies like DOI and USFS have aggressively promoted “home hardening” and the establishment of “defensible space” to homeowners and communities, they have failed to carry out these measures for historic structures they steward on behalf of American taxpayers. By integrating AI‑enabled, dynamic risk modeling with a full spectrum of contractor-scaled treatment and neutralization strategies, agencies could position treatments where they will have the greatest impact, particularly in the wildland‑urban interface (WUI), where the stakes are highest.

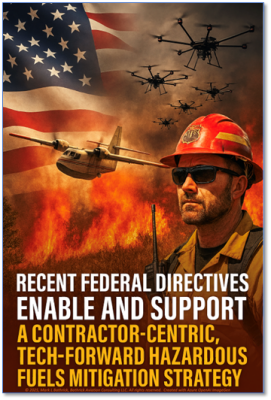

Federal Unity, Private Innovation: A New Era in Wildfire Mitigation

The Empowering Commonsense Wildfire Prevention and Response Executive Order (EO 14308) of June 12, 2025, directs DOI and USDA to “consolidate their wildland fire programs” and produce a “comprehensive technology roadmap… including through artificial intelligence, data sharing, innovative modeling and mapping,” while promoting a “risk-informed approach” and year-round readiness.73 It also calls for expanded partnerships, compacts, and mutual aid, which lowers friction for state, local, tribal, and private-sector participation.

When paired with instructions to identify and eliminate bureaucratic obstacles that hinder prevention, detection, or response, and the implementation of performance metrics, this establishes clear authority, resources, and accountability to bolster contractor-enabled capacity, deploy autonomous/aerial ignition solutions on a large scale, and integrate AI-driven risk targeting before and during the fire year. The EO further instructs EPA and USDA to consider modifying rules hindering prescribed fire and fire retardant use, and DoD to declassify satellite datasets to improve prediction—directly supporting just-in-time chemical pretreatments informed by dynamic intelligence products.

In response to the EO, DOI and USDA’s joint September 15, 2025, Wildland Fire Service Plan announcement emphasizes a “joint federal firefighting aircraft service,” “consolidate predictive services into a national intelligence capability,” and “establish a joint contracting, procurement and payment center,” while “deploy[ing] a unified wildfire risk mapping tool” and “expand[ing] beneficial use of biomass.”74 It explicitly notes opportunities for the private sector to contribute suggestions, signaling an open door to contractor-centric models for scaled prescribed burn capacity, aerial ignition, and pretreatment logistics tied to national intelligence and risk products. These enterprise reforms—unifying aviation, predictive services, and procurement—are the connective tissue needed to embed drones (including swarms), contractor-delivered ignition, targeted long-term, short-term, and just-in-time pretreatment strategies, and AI-driven dispatch in a single, accountable framework.

USDA’s Secretarial Memorandum 1078-017 operationalizes these reforms: it orders “modernization of the federal wildland fire aviation program through unified… procurement [and] contracting,” initiates “joint USDA and DOI procurement, contracting, and payment centers,” and consolidates Predictive Services into a centralized “Fire Intelligence” function.75 It mandates a “unified Wildfire Enterprise IT architecture,” a “joint governance structure” for research and tech, and the use of a “unified wildfire risk mapping tool” to plan mitigation and show risk reduction across all ownerships. It also calls to “eliminate regulatory barriers for prescribed fire and use of fire retardant.” Together, these actions pave the path for outcome-based, multi-award contracts that onboard vendors quickly, align aviation standards for new platforms (including drones and swarms), and couple AI-enabled targeting with approved chemical pretreatments deployed on long-term, short-term, and just-in-time timelines.

Finally, Secretary’s Order 3443 elevates and unifies DOI’s wildland fire programs and—per the joint announcement—directs establishment of the U.S. Wildland Fire Service with an implementation plan by January 2026.76 This is the governance cornerstone that enables common standards, shared procurement, and centralized intelligence to translate policy intent into executable acquisition packages, performance metrics, and field deployment—conditions necessary to scale contract-based aerial ignition (including UAS swarms) and targeted chemical pretreatments guided by dynamic, AI-enabled risk assessments.

Charting a Path Forward to New Thinking and Improved Risk Mitigation

Fuel plays a pivotal role in both wildfire occurrence and behavior. Based on the current hazardous fuel treatment backlog and projected growth rate, there is an urgent need for modernized fuel management strategies to defuse America’s wildfire time bomb. By applying the proven contractor-centric aerial firefighting model to fuel treatment operations such as prescribed burning, we can integrate advanced drone technology for aerial ignition and timely, targeted fuels neutralization through existing government-approved pretreatments. Additionally, leveraging AI-driven risk assessments and overcoming cultural and organizational barriers will enable us to begin turning the tide. This comprehensive approach not only focuses on the immediate reduction of hazardous fuels but also ensures the timely protection of critical infrastructure and communities through appropriate neutralization measures. By embracing these solutions, we can effectively confront the escalating wildfire threat and safeguard our natural landscapes for future generations.

Comments