In March of 2020, the commenting period on the NPRM on Remote ID had closed with over 52,000 comments to the FAA. A hotly debated topic, the biggest question that hung in everyone’s minds was whether the FAA was going to rollout a networked only rule or not. For hobbyists, many individual pilots, and emergency response the cost, the potential privacy issues, and challenge of coming up with a networked signal was too steep. Many in the drone community thought that a rigid network-only rule would be a non-starter.

After the FAA digested those 52,000 + comments, they ultimately agreed and went with broadcast only, leaving many relieved with the change and others concerned about how the limitations of broadcast could impact the future of commercial drone operations and whether broadcast could also present privacy issues, perpetuating the debate of broadcast versus network.

Broadcast vs. Network

Remote ID seems to have split the drone community into two camps: networked and broadcast. But the original idea was never intended to make this separation. It is worth taking a step back to point out that the ASTM International, a globally recognized industry-consensus standards body, which organized a consortium to create a Remote ID standard, never advocated for one or the other, but rather an either/or/both scenario, as Luke Fox, CEO of WhiteFox, pointed out to Commercial UAV News.

“ASTM International published a Remote ID standard in December 2019 (ASTM F3411–19),” said Fox. “After about two years of work, experts from academia, Fortune 500 companies, drone manufacturers, and drone startups were able to reach a consensus on what Remote ID should like for drones. The December 2020 Final Rule on Remote ID differs in one major and some minor areas from the ASTM standard. Whereas the ASTM Standard was bifurcated to allow either Network Remote ID or Broadcast Remote ID, or both, the Final Rule prohibits Network Remote ID as an acceptable form of Remote ID.”

What this means is that ASTM concluded that neither broadcast nor network could be a one-size-fits all solution. There are pros and cons to each solution, and both need to be available in order to fully support the industry. This is an important distinction because it explains to a large degree why there is a separation between the two camps—neither solution works entirely on its own, it works for some scenarios and not others.

It is unclear as to why it came down to one or the other, but at least for now, it is broadcast only. Why it is broadcast only (again, at least for now) and not networked is something we can and should dive into because it points to where we are as an industry.

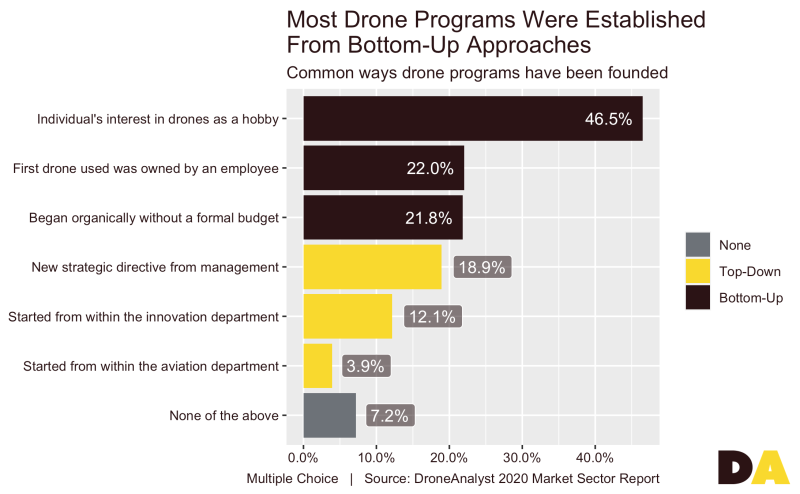

In a recent research study, DroneAnalyst concluded that it was hobbyists who have mostly unlocked the potential of commercial drone adoption, citing that in a survey of nearly 500 companies, 68% of drone programs were founded through bottom-up approaches (i.e., bringing a personal drone into work as a result of a hobby) rather than top down (i.e., through innovation or R&D departments, as an executive directive, or as part of an aviation department initiative).

Image Courtesy of DroneAnalyst

DroneAnalyst went on to point out that this gives the hobbyist group a considerable amount of power in the commercial drone industry, one that can be seen in the final result of the Remote ID rule.

“These data highlight that – in these early days – the industry has relied on the hobbyist segment for growth,” pointed out David Benowitz, Head of Research at DroneAnalyst. “That should influence the decisions made by brands, and how regulators consider new rules. The effect of the industry’s hobbyist roots is best shown through the new FAA Remote Identification (RID) rules. After receiving over 53,000 comments – many concerned that network RID could harm the hobby – the FAA shifted to solely requiring broadcast RID instead and allowed for the creation of FRIAs. The FAA’s actions should not just be seen as supporting hobbyists but securing the growth of the commercial drone industry.”

But even though broadcast remote ID suits the needs of those who are defining and growing the commercial drone industry of today, and should help with short-term growth, Benowitz was also careful to point out that this trend is expected to change as the industry matures.

“While this trend may be expected in the early days of a new industry, we assume this trend will reverse as solutions mature and the ROI of drone-powered solutions become better established. The solutions today are rudimentary compared to the autonomous, drone-in-the-box data acquisition solutions dreamed up by innovation departments,” stated Benowitz. “This data shows that the drone industry has risen despite this solution immaturity. Hobbyist pioneers have turned today’s drones into piloted data capture tools, helping to fund future innovations through their purchases. Despite our expectations that this trend will shift long-term, we aren’t seeing this shift yet.”

The question is: Will broadcast be able to mature with the industry when this shift happens? There are a number of industry innovators who think a broadcast only solution falls short of what will be needed for that mature future.

“Broadcast RID has a minimal useful range, a constrained data payload measured in bits, with no ability to customize or secure the data for the audience. Basically, the same limited message goes to everyone. Best case scenario is it’s a baseline for one-way communication for those in range,” explained Jon Hegranes, CEO of Kittyhawk, to Commercial UAV News. “With network, you have the ability to share richer data to different audiences, doing so in a centralized and real-time manner via the ubiquitous internet. For example, data sent drone-to-drone could be different from data shared with trusted entities such as law enforcement. At the same time, another data message can be made available to drone operators and the general public. With each audience and use case, you can ensure security and privacy while optimizing the data sets, data frequency, and—most importantly—with the ability to send a return message. UTM will require multi-way and multi-layered communication. Just because I may be lucky enough to read your broadcast Remote ID message, doesn’t mean that my drone can communicate back with pertinent information about prioritized routing or necessary deconfliction. This multi-way, centralized, shared, and networked communication layer is how we not only get to BVLOS, delivery, and AAM—it’s how we scale.”

Hegranes, and others who have an eye toward realizing the maturity of the industry, sees network as the only way to achieve the level of sophisticated security, safety, data, and communication required for advanced operations and autonomous missions. These operations will be conducted at a scale and complexity never before seen in the national airspace, and it will most likely require the addition of networked UTM to achieve it.

This is probably why the FAA left the door open for networked rulings in the future. Broadcast works for the majority of jobs and users today, but the long-term situation will need something far more sophisticated for long distance and autonomous applications, such as the need to deconflict in air autonomously through two-way communication.

Broadcast Remote ID will most likely need to be augmented with networked solutions as the industry matures, but there are some more immediate challenges the industry will have to sort out as Remote ID is implemented.

The Immediate Challenges of Broadcast

There are some immediate challenges to rolling out broadcast, especially in regard to spectrum and privacy.

Similar to other rules released by the FAA, the Remote ID rule defines criteria for what is required without being prescriptive about what that specifically means, that means many people may come to the FAA with multiple solutions that all meet that criteria—this can get tricky for the industry, especially when considering which spectrum to broadcast over. When asked about what the industry could do to mitigate these issues Luke Fox said that this could get complicated and problematic.

“There are still many open questions about how cross-functionality will work in practice,” Fox explained. “Interoperability is critical for Remote ID to accomplish its stated goal of helping to ‘mitigate risks associated with expanded drone operations,’ according to the FAA press release on the Final Rule. Imagine having a drone operating within a TFR with an approved Means of Compliance (MoC). Yet, no one on the ground can receive the Remote ID message, thus instantly categorizing the drone as a threat. My bet is that this risk might be mitigated to some degree in that many will use the updated ASTM standard (after it is approved as an MoC) as a baseline. However, this cannot be guaranteed.”

Drones broadcasting on multiple frequencies could quickly complicate things, especially for law enforcement who needs access to all Remote ID broadcasts and may need multiple receivers to do so. The other problem is how we will be able to receive the broadcast once the spectrum is set.

“The biggest unknown at this point is how anyone will make a Remote ID broadcast that can be received by “personal wireless devices that are capable of receiving 47 CFR part 15 frequencies, such as smartphones, tablets, or other similar commercially available devices” (FAA Remote ID Final Rule p. 75),” continued Fox. “There is simply no known broadcast method where you can have a drone flying at the common legal altitude limit of 400 feet and pick up a random cell phone on the ground to receive a Remote ID broadcast. It simply does not exist. The reason is fairly simple, while cell phones are ubiquitous, they were not designed to receive random unilateral broadcasts. People have gotten creative to demonstrate a variety of methods, but at best, they work with a small minority of phones and at insufficient ranges. For example, Japanese government researchers ‘using Bluetooth 5.0 to conduct tests to confirm the success rate of communication between a drone flying at an altitude of approximately 150m with a prototype transmitter and a prototype evaluation receiver located on the ground and confirmed the performance of a maximum communication success rate of 95% at a horizontal distance of 300m.’ Let that sink in; using the longest-range method, you can only identify a drone at 75% of the legal altitude and only use a special transmitter on the drone (rather than the integrated transmitter) and only use a particular receiver (not your average cell phone).”

In short, even though your drone may be squawking, there may be no one equipped with the technology to properly receive it. This may be good news for people who are concerned by the general public picking up a signal and putting pilots at risk—one of the topics that will be addressed in our upcoming "Ask the Experts Remote ID Panel" on February 8th starting at 12:00 PM EST—but this could pose a challenge for law enforcement who need to monitor these operations, especially if different drones are using different spectrum frequencies.

Conclusion

The immediate challenges of rolling out broadcast Remote ID and the long-term concerns some have about how it will or won’t be able to support advanced operations are two key topics for debate that will most likely continue into the years to come. But the solution may not be in an either/or scenario but rather in enabling both technologies, as the ASTM standard originally recommended. Cutting one or the other out ultimately does not serve the needs of the entire drone community and is limiting the technology to what it can do today, rather than looking at the future maturity of the industry. Let’s hope that the window left open by the FAA in this current ruling eventually becomes a door.

Comments