On December 30, 2023, a helicopter and drone collided in midair near the Daytona Beach International Airport (KDAB) creating a storm that went beyond the destruction of the drone and the relatively minor damage to one of the helicopter main blades. Part 1 and Part 2 of this series focused on what happened as the investigations by federal agencies were taking place. Part 3 focuses on the protagonists, and we made every effort to contact every single one of them and give them an opportunity to tell their side of the story.

What began as a routine investigation turned out to be a precedent-setting event that required the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) to unpublish the first version of the Final Accident Report on January 25 and re-publish it on February 20.

Now that the NTSB and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) investigations are over, we reached out to the various protagonists whose decisions made it possible for a helicopter to fly right into the path of a drone flying a routine autonomous photogrammetry flight.

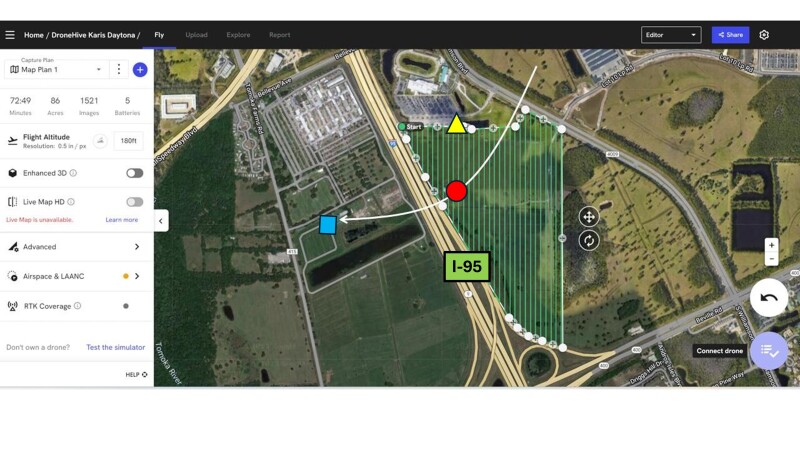

It all began in early 2023 when the FAA issued a ”Certificate of Waiver or Authorization” or COA to the construction conglomerate Clayco Corp. This specific COA covered the unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) flights on a clearly defined polygon, half a mile south-southwest of KDAB. Given the proximity to this important Florida airport, the COA restricted the flight to 150 ft. AGL (above ground level) and required the UAV Pilot in Command (PIC) to contact the KDAB tower 15 minutes in advance of commencing operations and upon completion of the flights.

These COAs issued by the FAA are particularly strict when assigning responsibility, and, in this case, the Responsible Person is Mr. Antoine Tissier, VDC Drone Operations Manager at Clayco Corp. When asked to comment, Mr. Tissier responded:

“Since that incident we updated briefing and training content, to clearly identify who does what and when to make sure everything is covered and confirmed, and we included deeper review of CoA with each pilot one by one.”

Instead of using their own pilots, Clayco Corp. hired DroneHive to perform the flights under Clayco’s COA. DroneHive is a UAV service provider that hires freelance drone pilots throughout the USA to perform flights for customers. We reached out to Michael Walcker, Safety Officer, and Paul Huish, Founder & CEO of DroneHive, and both declined to comment.

In this case, DroneHive hired a drone pilot with over 400 hours of experience and who owns his own drones. We reached out to the pilot for his comments, and he responded:

“I have worked for many organizations for over four years, and this was the first time I had an accident.I made a big mistake by not reading the COA carefully, and that day was the ninth time I made the same flight and I clearly remember having seen that helicopter or another of a similar color on previous flights flying around the area in which I did the mapping but never flew over it. That day, as well as the previous days, I was flying at 180 feet AGL and my drone was hit by the blades of a helicopter that suddenly appeared above me flying from the northeast to the west crossing over the construction, then over I95 until reaching its landing area and landing. I am very surprised by the fact that from the point of impact to the landing area of the helicopter there are approximately 1,700 feet and that at that distance from its heliport it flew at such a low altitude to pass over I95.”

At this point, it is important to note that the pilot, on eight previous occasions, not only flew the mission, but also submitted the result of the flight in terms of a cartographic product to Clayco directly. All these photographs and the resulting maps were clearly marked with a flight altitude of 180 feet AGL.

“When I was assigned this job, my employer sent me a KLM file where the mapping area was clearly identified, I realized that it was right next to the Daytona Beach International Airport, and I knew that I would need to unlock my drone to be able to fly there,” the pilot said. “I tried a couple of times requesting the unlock in the DJI Flysafe Unlock application but both requests were rejected, I immediately contacted the company that hired me and it was at that moment that they notified me that a COA existed, they sent it to me and I proceeded to request the unlocking again, as I mentioned before, I did not read the COA carefully and that is why I requested the unlocking to make the flights at 180 feet and the request was approved by DJI. A curious fact is that to complete the request the application needs that you upload the file with the COA to be reviewed but even more curious is that because I assumed that the application works with feet, I did not realize that there was a tab where you can change from meters to feet and I never changed that, that is, my request was submitted to fly at 180 meters and despite DJI asking for the COA to review and unlock the drone, the request was approved to fly at 180 meters (590 feet) less than half a mile from the airport, which tells me that the DJI's verification process is unreliable and for me it is another lesson that as a pilot I must verify every detail before flying.”

In previous articles, we have warned about the dangers of giving a foreign manufacturer the right to allow FAA-licensed pilots to flight in the National Airspace (NAS) and this authorization at 590 feet is just a small example of the potential for further mishaps.

We reached out to DJI for comments and they sent us the following statement:

"DJI first set up voluntary geofencing systems in 2013, long before geofencing was acknowledged by industry and government stakeholders alike as a key feature to ensure drone safety. This was not mandated by regulations, similar to how automobile manufacturers are not required to include built-in geofencing. While there are certain locations where driving is inappropriate, drivers are expected to adhere to traffic laws and driving regulations.

The process of unlocking geofence is established based on the mutual trust between DJI and its end users. We recommend end users to first secure authorization document to fly in the area where they request to unlock. DJI will then evaluate the request based on the provided information to decide if the request should be granted. We reject requests that are unable to present proper official documentations. Our principle is to remind users to obtain necessary authorization from officials. Therefore, when users upload official documents such as COAs, we trust that they have fulfilled compliance requirements and fully understand the potential risks associated with unlocking geofences.

Based on the NTSB report, we were able to locate the drone pilot’s requests in our system. We can confirm that the pilot did submit a request for an altitude of 180 meters. On our website in the U.S., the altitude column is set to feet by default. If end users need to request altitude in meters, they must manually adjust the setting. We also observed that the pilot had previously submitted two additional requests in the correct unit. The first request was for 50 feet, followed by a second request for 55 feet.

Compliance with local regulations and restrictions is the responsibility of the end user, as it is with any consumer product. We will continue to collaborate closely with the FAA to educate end users on safe and responsible flight practice.”

Initially, the NTSB published a Final Accident Report on January 25 that gave the impression that the accident was between a helicopter and a rogue drone. We are convinced it was not their intention to do so, but the lack of previous experience investigating accidents between traditional aircraft and legal drones justifies their confusion.

On January 26, we submitted a comprehensive report in which we gave the NTSB investigator, Mr. Joshua Young and his FAA counterpart Mitchell Salley, all the information they needed to correct the report in a way that would reflect more accurately a mid-air collision between two legally FAA-registered aircraft.

On January 31, the initial report was removed from the NTSB website. It was republished on February 20, qualifying the accident as mid-air collision, mentioning that the drone was operating under Part 107, and providing details on the drone make, model, serial number, and FAA registration, as well as drone pilot details.

On February 15, we received a call from Kristi Dunsk, Deputy Director, Regional Operations, Office of Aviation Safety, NTSB in which she expressed the gratitude of her agency for our report and the various points that it raised. She put emphasis on the fact that there were a number of simultaneous investigations of serious aviation accidents and the initial Final Report was less than ideal.

It is appropriate to remember that just seven days after the Daytona Beach midair collision, the Alaskan Airlines door plug blew up creating a serious situation for hundreds of Boeing 737 Max aircraft all over the world and requiring the NTSB and the FAA to dedicated an incredible amount to resources to that particular investigation.

The fact remains that after receiving our report, the NTSB corrected the report and now, we have a version that recognizes an accident between two FAA-registered aircraft with two FAA-licensed pilots. We reached out to Ms. Dunks for comments specific to this article and received the following statement:

“The midair collision between the drone and helicopter highlights the importance of the drone rules and regulations that are in place and the responsibilities of all who operate within the national airspace system.”

And at this point we need to talk about the the helicopter and its pilot who was PIC of N828AK when the collision happened. We reached out to the pilot through his employer, Leading Edge Helicopters but have not heard from him or the company.

The COA issued to Clayco Corp. in early 2023 generated a NOTAM (notice to aviators) in which the entire area of the construction site from surface to 200 feet was marked as possible UAS activity within 0.25 nautical miles (nm) of a set of coordinates that mark exactly Clayco’s construction site. This means that pilots of crewed aviation were warned in advance that there was possible drone activity and flying below 200 feet near those coordinates was dangerous.

In the initial NTSB report, the drone pilot was found to have issues with “Decision Making/Judgement” and possible deficiencies in “Knowledge of Procedures.” In the new report, both pilots were found to have deficiencies with exactly the same issues.

In most cases, NTSB findings do not generate any concrete actions because that is not the mandate of the federal agency, but the situation with the FAA is different. The FAA is mandated with improving safety, and these investigations typically generate letters to the affected pilots in which the federal agency states that they have reasons to believe that the pilot to whom the letter is addressed is not qualified to hold a pilots’ license and needs to prove to an inspector he or she is. In most instances, this is done by holding an in-person interview at the local FAA FSDO (Flight Standards Field Office) in which a seasoned aviation inspector will conduct a lengthy conversation with the affected pilot to determine if his/her license should be revoked or not.

In conclusion, everyone involved in this accident from the customer (Clayco Corp.), the intermediary contractor (DroneHive), the drone manufacturer (DJI), the drone pilot, and the helicopter pilot contributed in one way or another to the midair collision, either by action, inaction, omission or ignorance. Thankfully, there were no fatalities, injuries or substantial damage, except for the drone which was destroyed.

This accident marks the first time the NTSB investigated a midair collision between a helicopter and a legal drone, but it will not be the last. We, as an industry, need to carefully study this accident and learn from it. Drone pilots need to realize that when they takeoff, they are entering a system that has been in place for decades with an enviable safety record. On the other hand, helicopter pilots need to understand that the skies below 400 ft are no longer the empty skies of yesteryears, and that aviation has changed dramatically, and it will get more crowded as flights beyond the visual range of the operator (BVLOS) are sanctioned in the next few months.

Comments