The uncrewed aviation industry is currently living through an exciting time—but it is also a time of high anxiety as we wait for the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to allow flights beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) and for autonomous (or at least semi-autonomous) flights to open an era of savings and reduced carbon footprints.

Among the main goals of our industry is finding ways to replace the occupant of the cockpit with a series of technologies that can do what a human pilot can do in a more reliable, more predictable, and safer way. But what is safe? And are today’s pilots good at these cockpit tasks?

Collision Avoidance in Aviation

To answer these questions, let’s consider the way the FAA defines Collision Avoidance (CFR 14 91-113 (b)):

“General. When weather conditions permit, regardless of whether an operation is conducted under instrument flight rules or visual flight rules, vigilance shall be maintained by each person operating an aircraft to see and avoid other aircraft. When a rule of this section gives another aircraft the right-of-way, the pilot shall give way to that aircraft and may not pass over, under, or ahead of it unless well clear.”

When it comes to see and avoid, general aviation pilots have a poor safety record, at least by looking at the statistics of mid-air collisions (MAC) or near MACs (NMAC).

- Average number of MACs in the US each year: 15 to 25 (70% fatal)

- NMACs a year: 200 (reported)

- Typical meteorological conditions: visual flying rules (VFR)

- Most common time: Between 10:00 am and 5:00 pm on weekends

- Average experience of pilots: 5,000 hours.

- Over 70% of incidents within 5 miles of an airport

- 50% inside the traffic pattern

- At altitudes of less than 1,000 feet.

Ultimately, the uncrewed aviation industry is trying to replace an imperfect see and avoid system that has been in use for over 100 years. We are trying to replace a mediocre way of doing things with an unproven, better way. It’s not an easy choice.

When it comes to flights in instrument flying rules (IFR), the statistics are certainly better. There has not been a MAC of commercial airliners in decades. However, this flying mode is heavily dependent on human air traffic controllers (ATC) (of which there are not enough already), radar coverage (not available over the entire country), Automatic Dependent Surveillance & Broadcast (which has significant limitations with respect to volume), Mode C and S transponders, and onboard Traffic Alert and Collision Avoidance Systems.

See and Avoid With Uncrewed Systems

These are all expensive and hardware-heavy devices that would add weight to small drones with already short flying times because of battery limitations. Most flights in uncrewed aviation use a combination of IFR and VFR techniques. The aviation community, including the FAA, is toying with the idea of creating a third category—Digital, Automated or Uncrewed Flight Rules or DFR, AFR or UFR—to fit the unique characteristics of uncrewed flying. In fact, the BVLOS Advisory Committee’s March 2022 report to the FAA included recommendations surrounding Automated Flight Rules.

The Limitations of Human Sight

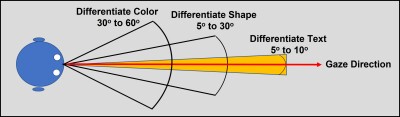

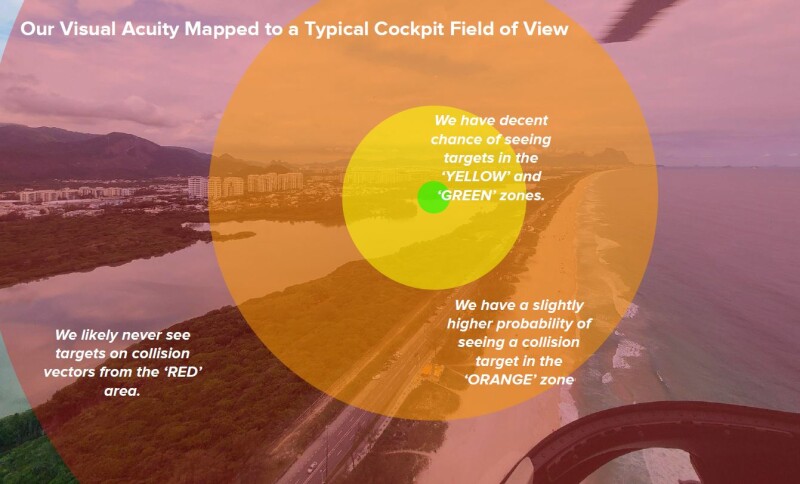

But let us go back to the issue of the human pilot and his/her ability to “see and avoid” aircraft during flight. The human eye is probably one of the worst sensors that we can use for this task. For one, it can only see and classify objects that are directly in front of it and hitting the eye’s macula or fovea centralis head on.

During the initial flying lessons to obtain their private certificate, every pilot is trained to scan the sky in search of other aircraft. The technique is simple and requires a systematic scan of the sky right in front of the aircraft, through the windshield. This method assures that the eye’s macula will be directed at every point in the field of view in order to see and classify objects in the sky.

Given the number of MACs and NMACs over the US in recent years, it is time for us to re-examine the validity of the assumption that in modern aviation, the human eye is an adequate sensor for the task.

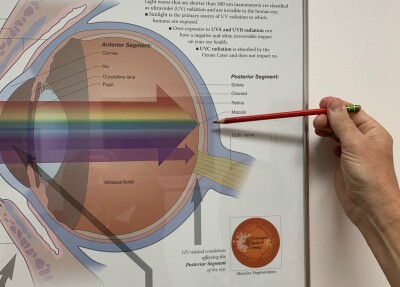

In order to better understand the reality of the human eye, we reached out to Dr. Robert Middleton, OD, a Boca Raton-based licensed optometrist for his expert commentary.

“The human eye is only a good sensor for detail in the area straight ahead and at images hitting directly at the Macula or Fovea Centralis, about 10% of the entire surface. I’m not an expert in camera acuity but I can assume that the sensor inside a camera covers 100% of the field of vision and registers every pixel with the same accuracy, very differently than the human eye,” Middleton said.

There is also the issue of age and the reality that the average age of a general aviation pilot is about 44-years old, with thousands of pilots in their 60s and 70s still active.

“The human eye reaches peak acuity at 35-years of age and begins a steady decline after that. The degree of deterioration and time of it depends on each individual but the decline is certain and unavoidable,” Dr. Middleton said.

When we described the methodology for scanning the sky in aviation, Dr. Middleton elaborated on the limitations of the human eye.

“Human eyes are not the best sensors for detecting non-moving objects in 90% of the field of vision,” Dr. Middleton stated. “If we see movement in the peripheral area, we instinctively move our heads to center the macula on the moving object to classify it.”

A Better Way

Unfortunately, MACs and NMACs always happen when one aircraft is heading at another (rarely straight on). In these instances, the approaching aircraft seems to be motionless, and it just grows imperceptibly slowly until it is too late.

So, for uncrewed aircraft, how do we convince the FAA that modern sensors with 100% acuity in the entire surface of the field of view is a better solution than the human eye?

Jon Damush, CEO of Iris Automation, has embarked in a crusade to convince the FAA that there are better ways to detect air traffic than just relying in the human eye. His company develops and manufactures optical aircraft detection systems. While the primary application of Iris’ system today is for uncrewed aircraft, in his opinion as a traditional aviation private pilot, this technology can and should be applied to crewed aircraft as an added layer of safety.

“As we look at the growth expected in aviation over the next couple of decades, we are not only going to see new entrants like drones and autonomous cargo aircraft, but we will also see an increase in simplified pilot operations and increasing autonomy in the cockpit of piloted aircraft,” Damush said. “By and large, this is a very good thing, but it also means there will be many more aircraft in the sky, and the sky isn’t getting any bigger. We need a way to ensure that no two aircraft ever collide in mid-air, and that is what we are building.”

There is hope, however. The BVLOS ARC report recommended specific changes to the rule language for the FAA when it comes to right of way rules and 91.113. Perhaps the simplest recommendation is to change 14 CFR 91.113 to say, “detect and avoid” instead of “see and avoid,” thus creating a legal entry of better sensors in the sky. We are also seeing significant attention on this matter from the FAA itself as the agency works to enable some very beneficial use cases of drones, like law enforcement, emergency response, and critical infrastructure inspection. Throughout 2022, the FAA has demonstrated a willingness to use the recommendations in the BVLSO ARC report to enable these use cases on a case-by-case basis.

When asked what he thinks the next steps should be from the FAA, Damush said, “We need to get past the case-by-case approvals and start to approve standard use case and concept of operations ‘templates.’ Couple that with approvals of technical approaches to safety as alternate means of compliance to existing rules. Then we will see safe, scalable and repeatable uncrewed flights in our national airspace.”

With the technology available today and an understanding of the limitations and inevitable deterioration of the human eye, it is time for the FAA to modernize the language in the regulation, thus opening the door for innovation and increased safety.

Comments