For many in the drone industry, the key to integrating unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) with manned counterparts in the national airspace (NAS) is the ability to fly without relying on the existing air traffic control (ATC) infrastructure. This has been a challenge for the industry since we first embarked on integrating the NAS. In order to realize the benefits of contact-less deliveries, and economic savings of aerial operations at every level and in every industry, this integration has to occur, but not without sacrificing the safety of the skies for those in the air and on the ground.

Currently, manned aviation has a complete dependency on ATC to perform every single flight. This requires constant, uninterrupted communications with an air traffic controller from point A to point B. This is not a model that can be replicated if we are adding hundreds of thousands of small UAVs to the skies to deliver packages, perform cellular tower and bridge inspections, monitor key assets, and all the other invaluable tasks that drones are capable of doing on a daily basis.

The expectation is that unmanned vehicles need to fly unsupervised, safely staying away from fixed objects on the ground and moving objects in the sky. Many companies have developed interesting and innovative alternatives to conventional ATC. Unfortunately, global regulators remain understandably hesitant to open the doors to the airspace they have been keeping safe for decades with traditional ATC. But the continued goal of both regulators and most businesses is to build a separate, but connected, unmanned traffic management (UTM) system, capable of handling all unmanned traffic independently and only involve ATC when there’s an emergency or an unexpected event that would put lives and property at risk.

This is why Commercial UAV Expo Americas 2020 brought together a panel moderated by the universally trusted entity, NASA, to discuss where we are with this important and necessary step toward NAS integration. The panel represented the four corners of the UTM community: Operators, international representatives, and regulators and standards experts:

- Shana Whitmarsh – Co-Founder, Clearspace Aero

- Phillip Butterworth-Hayes – Editor & Publisher, Unmanned Airspace

- Praveen Raju – General Engineer, FAA

- Andy Thurling – Chief Technology Officer, NUAIR

- Parimal Kopardekar (PK) – Director, NASA Aeronautics Research Institute

The discussion began by a short presentation from each panelist, beginning with Whitmarsh, of Clearspace Aero and representing the operators.

“At Clearspace Aero we are working on Nextgen UTM beyond the simple command and control feature and into the artificial intelligence (AI) of completely autonomous vehicles that would be able to learn the good and the bad,” stated Whitmarsh. “Our goal is to develop a system that would encourage the growth of the industry based on the availability of a system that would allow these unmanned vehicles to join their manned counterparts in the NAS under command of ATC plus an independent UTM system enabled by (AI) especially under the umbrella of the Smart City concept.”

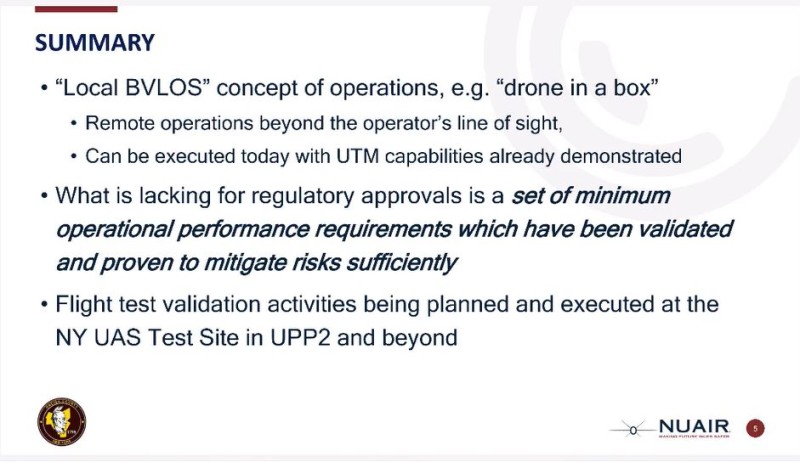

Thurling from NUAIR followed with a presentation about the development of standards at the NY Test Site.

“At NUAIR we are testing the effectiveness of UTM systems for small and large UAVs and looking forward to flying phase two of the FAA’s UTM pilot program (UPP2), before Thanksgiving,” Thurling explained. “Our approach is to start with the concept of local flights beyond visual line of sight or L-BVLOS and grow our expertise to eventually expand into full blown BVLOS in the NAS. We’re also working on a human-less preflight that would allow for more drone-in-a-box applications.”

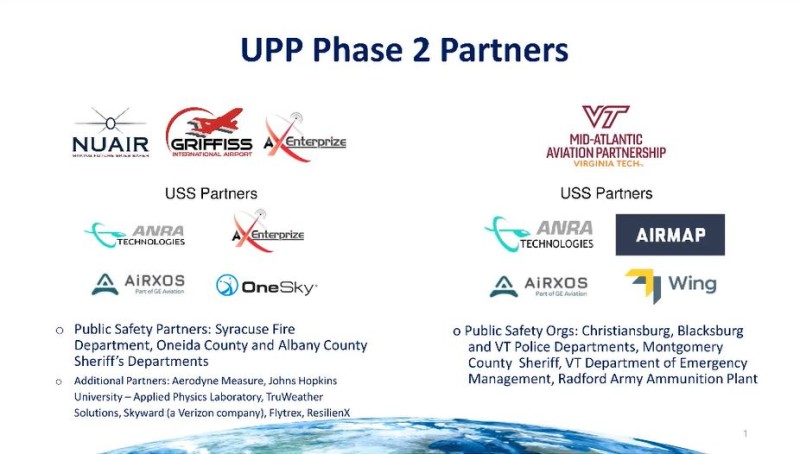

Raju from the FAA gave the audience the initial view from the regulator, making emphasis on UPP2.

“As the project manager for the UTM Pilot Project R&D, we are proud to work with our partners in phase two of our integration program,” he said. “Our goal is to keep testing UTM systems in controlled settings, until we can move forward with something that would allow integration into the NAS. The FAA is exchanging data with the industry to expedite the implementation of a workable UTM and is not 10, 20 or 30 years into the future, but just a few years away. LANNC is a good example of the FAA being agile when it needs to be. Industry is being tremendously helpful in the creation of a feasible UTM ecosystem, and that would benefit everyone involved.”

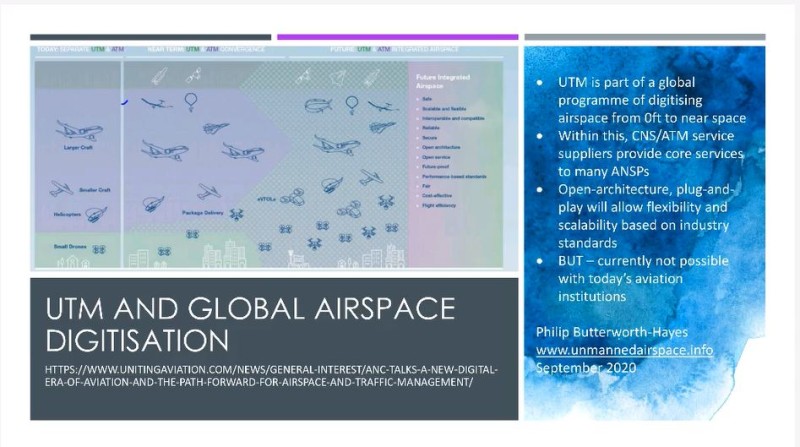

Butterworth-Hayes from Unmanned Airspace provided the audience with an introduction to the international perspective.

“There is a concerted European effort to unify UTM,” he said. “The main issue we are focusing in Europe is who pays?”

A question from the audience sparked a brand-new discussion: to name the most important things that need to happen in 2021 to advance the cause of UTM. Whitmarsh responded first by elaborating on her company’s efforts to develop a smart UTM system.

“Adaptation is the key to authorization of UAV’s in the NAS,” she said with conviction. “9/11 was an eye opener for me and the need for absolute security, but also the need to have a system that is self-sustaining. We are working on various business models that are based on the concept of plug & fly.”

“We all agree that we need to implement standards and regulations, as well as remote ID,” Butterworth-Hayes added. “But the issue to resolve over the next few months or years is privacy and sustainability.”

“Over the past year we have learned very well how to talk to each other in the air, but we have done a less stellar job in how well we navigate in it,” Thurling stated. “We must stop the ‘It Depends’ syndrome and work towards a model that can be implemented fast. Let’s not allow the perfect to be the enemy of the good enough.”

“The FAA is trying very hard to be more agile in this new era of non-traditional aviation,” Raju added, commenting from the regulator’s point of view. “We are looking at the model of incremental traffic volume of, not only UAVs but also Urban Air Mobility (UAM) in non-urban areas, or less congested zones, that would allow for a gradual deployment. We are studying three different areas, safety and efficiency, partnership with law enforcement with regards to Remote ID and helping the industry prioritize the standards in a near term versus a long-term approach, with heavy emphasis on what can be deployed in 2021.”

The moderator then steered the discussion to the final point of the panel: the technologies that need to be perfected in the near-term to overcome the challenges to a massive deployment and the beginning of the pay-off period.

Whitmarsh opened this new discussion by commenting on the efforts of her company towards a fully autonomous vehicle, “We’ve been working hard on a certain path, but the standards keep changing and remain undefined. Therefore, the speed of development is slowed by the lack of clarity around standards. We try to develop a solution as agnostic as possible to enable integration.”

Butterworth-Hayes gave us the international view by commenting on advances in Africa.

“Countries with less resources are adapting what already exist and making it work,” pointed out Butterworth-Hayes, “integrating with existing infrastructure in an effort to deploy faster while benefiting the community.”

Thurling then emphasized that use cases for saving lives can enhance community acceptance for drone applications, emphasizing that “Blood before Burritos” (or transfusions before tacos) would help pave the way for everyday drone missions.

“We are following very closely the international civil aviation organization (ICAO) trust framework study group and using their model to help us with our own local standards,” added Thurling. “Getting it right in a low-risk environment first and then building it into larger aircraft. Detect and Avoid (DAA) is a good example as it moves from sUAV’s into larger aircraft in an effort to reduce the number of mid-air collisions of general aviation aircraft. Our model of deployment should follow the ‘Blood before Burritos’ approach, as we convince the community that the drone industry is here to help save lives and that in turn will translate to an easier path forward.”

“We are also monitoring very closely the ICAO Trust Framework Group and the advances that Switzerland is deploying UTM over large sectors of their airspace,” echoed Raju. “We are starting at the 400 ft and below level and are planning for a universal UTM for other types of vehicles and other types of airspace. The architecture of this solution is the key, and it must be developed in a private/public collaboration and cooperation to help the FAA be more agile and come up with solutions faster.”

Whitmarsh made her final comments by outlining what, in her view, are the elements that need to be resolved to have a workable UTM:

“The key is a good communication standard. 5G is promising, but we need steady, continuous and simultaneous data exchange,” she concluded. “At Clearspace Aero, we are working on a plug & play model that would eventually be our main differentiator. Another key element is integration and the ability to register and fly by following the model of Apple and GoPro and being user centric. Finally, if you buy an autonomous vehicle, you need to be absolutely sure it will be accepted in the NAS, and that is at risk for the purchasing public if the standards keep changing.”

“I’m more concerned about the human limitations,” Butterworth-Hayes stated in his closing remarks. “These are not only new machines, they’re an entire new way to look at things and UTM might be the tool to make it all happen.”

In his final statement, Thurling emphasized his push for a sooner, rather than later approach.

“Let’s field something!” he exclaimed. “A hundred years ago aviation started by flying across the continent over concrete arrows on the ground, before nav aids existed, and it was a good starting point. As long as it’s safe let’s deploy something as soon as possible and do some business.”

Raju wrapped up the panel with words of encouragement.

“We are in a new golden age of aviation,” he said with conviction. “The FAA is working as hard as we can and being as agile as we can be to push things forward, but the unmanned community needs to understand that there’s a culture of safety and a very conservative approach to new things at the FAA.”

This UTM panel, in my opinion, was the most important of the day because it brought to light the issues between the regulator, the standards and an industry pushing for commercial success in a safe environment—a much needed frank conversation between all key stakeholders.

Comments