For a drone service provider (DSP) today, it’s clear that simply being able to fly a drone is no longer enough to separate oneself from the competition and build a business. The best DSPs know whatever industries they elect to serve, taking into account the people they’ll be working for, what their day-to-day needs are, and how to communicate the value drones can bring to their work. In looking at industries to break into, agriculture sits in a fascinating place within the ecosystem, as a vital industry for the global economy and society at large, one with plenty of financial might, and also a traditional industry that can be, at times, a bit resistant to new technology.

To be clear, agriculture has already been utilizing drones to varying degrees for years now. However, given the sheer size of the industry and how many individual farms and owners can benefit from the technology, there is still a large market share available to those looking to get into this space.

Generally speaking, there are two main uses for drones in agriculture. One involves more direct aerial applications, largely around spraying, whether it be for irrigation, fertilizing, or spraying pesticides. Alongside that application, there is also a data collection side to drone utilization in agriculture, for mapping and monitoring crops.

Recently, Commercial UAV News spoke with FlyGuys’ Jerimiah Contreras about the latter piece of the UAVs in agriculture puzzle. He talked about how he got his personal start in commercial UAV pilot experience within the agriculture space, how mapping plays into this industry, and how others can try to break into this field.

For FlyGuys’ part, Contreras reiterated throughout the conversation that they strictly work in this mapping segment of agricultural work, as spraying applications require different training, equipment, and general knowledge. Instead, they actually work as something of a third party with software companies that work directly with farm owners. Those software companies store, manage, and analyze data, but don’t have their own staff to go and collect said data, Instead, they contract companies like FlyGuys to go out to the site to fly and collect RGB and multispectral imagery. Although the company works in a number of different industries, Contreras noted that agriculture represents one of FlyGuys’ most fruitful sectors of work.

For Contreras personally, he told CUAV News that agriculture was one of the first areas in which he worked on a commercial basis before joining FlyGuys as a full-time pilot. Living in Southern California, he was looking for a way to help local businesses with his drones, and as there were a lot of date farms around him, it was a logical place to start. Unsurprisingly, he says there was some initial difficulty in getting owners on board.

“The first industry that I ever targeted with UAVs is agriculture,” he told CUAV News. “Personally, from my own experience, some of the farmers were a little skeptical [of the technology’s value]. They wanted to know how it could solve their specific problems, and where it could save them money.”

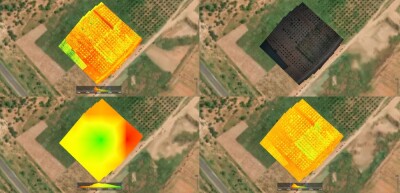

Ultimately, he had a few pieces of advice for those trying to get into this industry based on his experience first breaking into the space. One was that he had to be willing to showcase the value of UAV mapping with some smaller pro bono projects to show tangible value. He shared one example of using a multispectral sensor to track irrigation drips.

“I needed to be able to show that I can save money, and I can provide some value so that higher-ups will write the check,” he said. “[In one example], I ended up going to the site at midnight every night for two weeks, because that’s when they turn on the irrigation, and I could pick up the heat difference. So, I would go out there at midnight until 3:00 am and would fly the crops with the infrared, and was able to see the different moisture heat spots.”

Ultimately, in this example, the data Contreras collected with his drone showed the location of faulty drip lines within the irrigation system, which was reported to the drip line company and helped earn the farmer a full return on the equipment.

That is, of course, one specific example that can’t be replicated everywhere, but the point is to be creative and proactive in proving the value that you are able to provide with your specific knowledge and equipment. When asked what else he would recommend to those trying to break into this space, Contreras also mentioned speaking directly with farmers where and when they can. He noted that many areas have local agriculture organizations where owners regularly meet, and he was able to get face time and hold presentations with members at these meetings. He even found value in sitting in as a “fly on the wall.”

Contreras also spoke a bit about the technological needs for a drone service provider looking to get into agriculture, and how it may or may not differ from other applications. Here, he differed a bit from what some others would potentially advise. It can be common for those in the industry to encourage pilots to find a niche – in terms of both industry and technology – and become an expert in that area. Contreras feels the opposite way.

“I like to advocate for this a lot in the industry because others try to say to find a niche and stick to that niche, but if you think about the equipment that we have and the advancements of the equipment, there isn’t one piece of equipment, or one drone, that is specific to one industry,” he explained. “So by using this one drone for one industry, you’re really limiting your diversity [as a pilot and service provider]. Whether it’s an RGB drone, a multispectral drone, or a thermal drone, they can be used across many different industries.”

When thinking about the future of drones in agriculture, particularly for pilots and service providers working in the space, Contreras goes back to the separate types of drone work in the field between mapping and spraying applications. While they require different techniques and expertise, he sees further merging between the two areas. That doesn’t necessarily mean the same pilots doing both projects, but rather that the data collected from mapping projects, like those from FlyGuys, will continue to be utilized more on the spraying application side.

“One thing to look forward to is that farmers are going to be able to implement variable rate applications more easily than ever,” Contreras said. “With the traditional method of spraying pesticides or chemicals, they would just spray at an even rate throughout the entire field. Now with the data we have and the advancements in some of the spraying technology, they’re going to be able to take the data and apply a variable rate application, so they apply less in healthy areas and more in unhealthy areas.”

Ultimately, Contreras’ experience in providing drone mapping services to the agricultural industry, both personally and more recently as part of the FlyGuys team, showcases the difficulty in breaking into this well-established industry, but also the value that it can bring to both the farmers and the drone service provider. As technology continues to improve for drone mapping, and as the agricultural industry becomes more welcoming to new and proven technologies, the value on both sides only figures to increase, making it a perfect time to start looking at this space for an expansion of drone business.

Comments