One of my favorite topics during the recent Virtual Commercial UAV Expo 2020 was the discussion about detect and avoid (DAA). Why? Simply because without DAA there are no flights beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS). When we analyze what a pilot does in a cockpit, most of it is monitoring automated systems and then looking outside for potential hazards to his/her flight; in other words, pilots detect and avoid hazards during flights.

By removing the pilot from the equation with unmanned aviation, we need to replace that capability, and that’s why DAA systems today are so sophisticated, without them there’s no autonomy and no flights beyond the visual range of the ground observers.

So, with that in mind, the organizers of the virtual Commercial UAV Expo 2020 included a panel of experts to discuss the state of DAA systems, not only from the point of view of the technology, but also from the view of regulations and standards.

The session was moderated by Matt Clark from Hogan Lovells and included four panelists:

- Maxime Gariel, CTO, Xwing

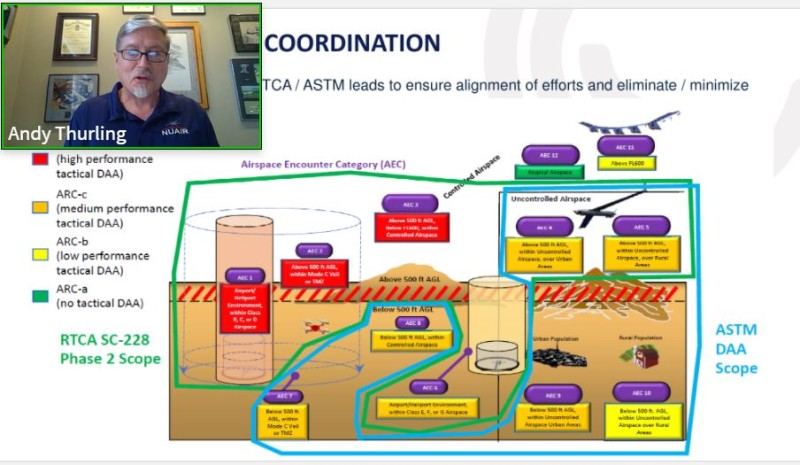

- Andy Thurling, CTO, Nuair

- Vijay Somandepalli, CTO, American Robotics

- Gary Watson, VP Solution, Fortem Technologies

Clark began the session by introducing the panelists and then gave each one the opportunity to present their companies and their reasons for being included in the panel.

Watson of Fortem Technologies opened the floor by making a short presentation on what his company is trying to implement in terms of DAA.

“The main objective of all our collective effort is to make sure we don’t put manned aviation at risk,” he said with conviction. “At Fortem Technologies we are developing ground-based and onboard radar solutions that offer superior detection, tracking, and classification of flying objects.”

Gariel of XWing explained that the goal of his company was to develop fully autonomous aerial platforms in the 9,000 lbs range and showed an impressive video of an unmanned Cessna Caravan fully automated taking off and landing without pilots, using only monitoring personnel.

“Our aim is to develop platform-agnostic, fully autonomous aircraft capable of performing unmanned missions in the thousands of pounds range,” he explained to the audience. “We work with Nasa and the FAA to incorporate three different sensors to the aircraft, including DAA, to make sure the flight is safe and as close to piloted as possible and even better.”

Somandepalli of American Robotics took a different route and explained why his company has focused on smaller vehicles for very specific missions:

“At American Robotics we have opted for the motto of ‘no pilot ever’,” began Somandepalli. “In other words, we are automating the process from beginning to end and that’s why we have introduced the concept of ‘drone-in-a-box’ in which a single box containing all the elements of the solution are deployed to the field and are allowed to perform its mission without human intervention.”

Thurling from Nuair then explained the role his organization is playing in the definition of standards for the development and deployment of DAA systems in the drone community:

“We need standards for DAA in order for the FAA to include them in the regulation when the time comes for the massive deployment of BVLOS flights,” he explained. “It is not always the most popular thing to do because different vendors are finding different ways to solve the problem of detecting and avoiding obstacles in the air, but unfortunately we need to have a solid understanding of the minimum requirements, otherwise it’s a free for all.”

After the four panelists expressed their point of view and presented their solutions, Clark asked a question from the audience, “How about maneuverability? How does it affect what the DAA is asking the aircraft to do?”

“With larger aircraft, the challenges are exponentially more difficult and the resultant damage if something goes wrong is way larger,” said Gariel, referring to the 9,000 lbs of his experimental aircraft. “That’s why we have selected to advance gradually testing the limits of what the aircraft can do and how the DAA system will handle these limitations.”

Somandepalli intervened to add: “With smaller platforms, the problems are similar, the DAA mandates a change of speed, altitude and heading and the vehicle needs to comply rapidly, without compromising the safety of the flight. This sometimes affects the mission and the reason to be airborne in the first place. Just adding DAA is not enough, the complexity is exponential when you mix with other safety systems.”

Clark then raised a controversial issue by asking how the standards will affect the different solutions being worked simultaneously all over the world. Gariel, whose company will obviously be affected by the imposition of standards jumped at the opportunity to express his opinion.

“We are quite concerned that the standards will not be compatible with every solution out there,” he stated adamantly. “And we believe the real issue is to demonstrate to the regulator that a particular solution works and does the job, not just comply with a standard.”

Thurling quickly intervened to clarify:

“We are aware that these standards will have detractors, but we are making every effort to make sure they’re inclusive and as general as possible.”

Somandepalli also clarified his company’s position:

“Having a standard is useful, but we, the manufacturers need to understand how the risk factors were calculated and how these factors affect different manufacturers, otherwise it’s exclusionary.”

Thurling then jumped into the discussion to use an example.

“The standards we are developing are similar to what had to be done with TCAS (Traffic Collision Avoidance System) years ago for manned aviation, and some manufacturers didn’t like it then, but today we have a fully compatible system in every aircraft that’s required by law to have it. TCAS and DAA do not perform the same task, but their deployment is a good example of what needs to be done.”

Clark then went on to ask: “How good is good enough?”

“It has to be better than visual observers!” said Thurling. “Risk ratios are not overly challenging, and the resulting systems will have to be pretty good.”

“It took ten years to mandate ADS-B (Automatic Dependent Surveillance and Broadcast) for manned aviation and the general aviation community fought tooth and nail to prevent its mandate.” Gariel pointed out in response. “Are we going to have to wait 10 years for DAA to be present in every drone? That’s a scary thought.”

“The FAA is a data-driven organization,” Watson added. “They’ll approve anything if you bring good data!”

Thurling ended the discussion by adding: “The general public will be more willing to accept these changes, and therefore the FAA more inclined to regulate it, when a defibrillator is delivered to a golfer at the 17th hole and the person survives. Examples like these will go a long way to bring the public on board and the regulator to allow these machines to take to the air.”

With this comment Clark closed the session. Listening to the manufacturers having a frank discussion in an open session with an entity working on the standards was an eye opener for me and, I’m sure, for most of the audience listening to the broadcast.

.jpg.small.400x400.jpg)

Comments