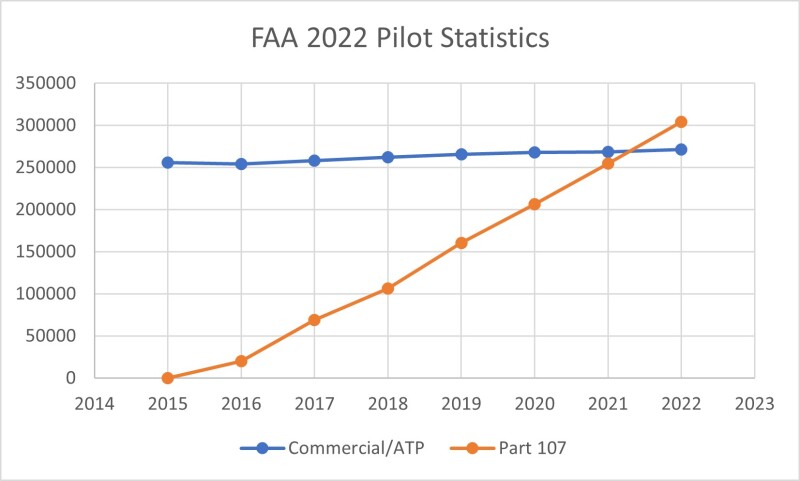

We first reported on this phenomenon a few months after the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) finalized Part 107 in the summer of 2016, when flight schools around the country began receiving requests for uncrewed aviation training. A group of traditional aviation learning centers saw an opportunity and jumped on it. Others preferred to stay away from Part 107 and continued training exclusively piloted aviation. At the beginning it was a trickle of enthusiasts curious about this new uncrewed industry but as the years passed, we have seen an evolution in which the number of Part 107 pilots now exceeds holders of traditional commercial and ATP (Airline Transport Pilot) combined.

Eventually, a new business model emerged. Flight schools exclusively dedicated to the training of Part 107 were created, such as the USA Drone Academy in Miami, and they began rolling out pilots at rates never seen before.

“We are currently preparing between 10 to 15 students a month for their Part 107 online exam and of those an average of eight, or approximately fifty percent, go ahead and present the test and pass,” said Rene Paez, CEO of the USA Drone Academy. “The numbers in the United States are not encouraging, and we believe that’s because the drone industry is a holding pattern waiting for the BVLOS regulation that would eventually require a large number of pilots.”

With the inevitable maturity of the industry, a new trend is developing as companies that adopt uncrewed aviation to improve their workflows, reduce costs, and increase workspace safety are now requesting that groups of pilots are trained in specific conditions.

We spoke with Claudia Rocha, Administrative Director of ADAHCOL one of the first flying schools in Colombia that saw the business opportunity in uncrewed aviation pilot training.

“Our flight school was founded by my brother, Capt. Sergio Rocha, who has over 40 years of experience in commercial aviation, and we began as a traditional aviation education center, training pilots to feed the huge demand for this profession in our country,” said Claudia. “Then, in 2013, we heard a rumor that the civil aviation authority in Colombia was exploring a formal regulation of uncrewed aviation and that started an internal debate about launching training services for drone pilots.”

ADAHCOL is located at the Guaymaral airport, one of the busiest general aviation airports in the country, strategically situated in the outskirts of the capital city of Bogota. According to DGAC statistics, 80% of all pilots in the country graduate from the various flight schools located at Guaymaral.

“The promise of a new revenue stream and adding a curriculum to the school gave us the push that we needed it to launch a virtual learning center, so we looked all over the world for an online teaching platform and in 2015 we announced our new uncrewed aviation course,” Claudia reported. “At the beginning, students trickled in, attracted by the online component about operations, weather, etc., but there was also an on-site component that forced everyone to attend in-person lessons on how to manipulate the controls of a drone.”

Companies in Colombia have found out that adding drones to the existing workflows can reduce operational costs, increase personnel safety, and save time, so they have started recruiting large number of pilots and training them as a group in order to have operational homogeneity.

“Suddenly, we received requests for training tens and sometimes hundreds of pilots a month from private companies that were launching internal drone programs,” Claudia said. “This development took us by surprise, and suddenly we found ourselves growing our facilities in order to satisfy the demand.”

Another aspect of training uncrewed aviation pilots is that there is a myriad of applications that require specific skills, and a generic training program was not necessarily what these companies were looking for.

“We received requests to train uncrewed pilots in very specific areas, such as agricultural spraying, infrastructure inspections, photogrammetry, thermography, cinema filming, and a few others,” Claudia said. “There’s a solid tendency of companies that have identified uncrewed aviation as means of improving their operations to establish their own aviation departments, and, for that, they need not only training but also the establishment of safety managements (SMS) or basic assessment risk systems (BARS) to handle aerial operations.”

The stark difference between the United States and Colombian markets might be rooted in the fact that skies are not as crowded, but also the regulator, in this case DGAC, is perhaps more open to work with private companies in the pursuit of a robust uncrewed aviation industry.

Comments