We are all anxiously waiting for the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to announce a regulation allowing uncrewed aircraft to fly beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS). The uncrewed aviation Industry, and most experts, believe that this move by the US regulator will unleash a massive deployment of applications such as package deliveries and eventually open the door to air taxis and the adoption of advanced air mobility (AAM).

The process that the FAA is following to reach what most people are calling Part 108 is somewhat confidential. That veil of secrecy is not exclusive to American and European regulators—it extends to any other civil aviation authority (CAA) grappling with the delicate balance between the safety of the flying public and the pressure to release these uncrewed marvels into the national airspace (NAS) of each country.

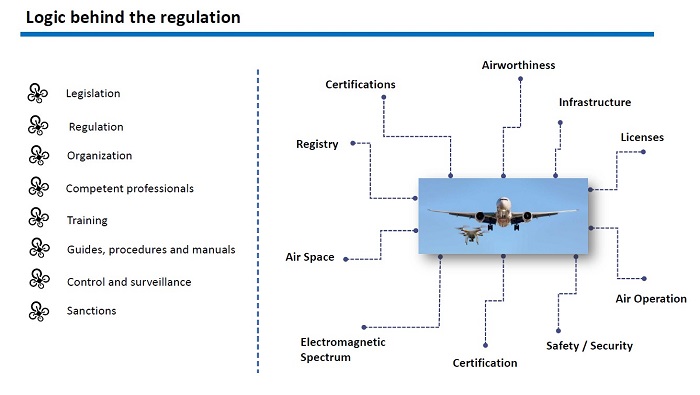

At the recent Elevate UAV Summit in Miami, organized by Drone Nerds, we had the opportunity to hear from the Colombian CAA (CAAoC), through a presentation by Mr. Robert Quiroga, the advisor to the director. Quiroga thrilled the audience with a comprehensive inside-view presentation about the history, the framework, and the future of uncrewed regulation in that Latin American country.

We had the opportunity to sit down with Quiroga before and after his presentation, and we picked his brain for a rare insight into the dilemma that CAAs around the world are facing.

“The balance between maintaining the current levels of safety and adding hundreds if not thousands of non-piloted aircraft to the NAS is delicate and requires a lot of diplomacy,” Quiroga said cautiously. “There are plenty of vocal stakeholders, but also the flying public that deservedly demands safety when they take a commercial flight. I have noticed, in the time that I’ve been in this job, that the issue is one of culture and inertia. Piloted aviation has been in place for 120 years and many of the processes and ways to do things go back decades, so it’s understandable that it will take a long time and a lot of technology to change the mindset.”

“The balance between maintaining the current levels of safety and adding hundreds if not thousands of non-piloted aircraft to the NAS is delicate and requires a lot of diplomacy,” Quiroga said cautiously. “There are plenty of vocal stakeholders, but also the flying public that deservedly demands safety when they take a commercial flight. I have noticed, in the time that I’ve been in this job, that the issue is one of culture and inertia. Piloted aviation has been in place for 120 years and many of the processes and ways to do things go back decades, so it’s understandable that it will take a long time and a lot of technology to change the mindset.”

Quiroga and his team in Colombia are facing the same headwinds of every regulator in the world, as they are the ones who must find a way to integrate crewed and uncrewed aviation over controlled airspace. Industry, academia, and research institutions are providing valuable information and insights, but at the end of the day each country’s CAA will have to decide which is the best way to make this integration happen in their respective NAS.

“Civil aviation authorities are regulators, not the air police,” Quiroga emphasized. “We are facing an issue of culture and education, and the same applies to a traffic light that everyone knows what red, yellow, and green means. We need to develop a similar process for both piloted and non-piloted aircraft in which we all agree what it means to have certain rights and privileges. We are dealing with a lot of challenges in the CAAoC with decades of experience doing things in a certain way, and there’s still a lot of work to do.”

In December 2022, Quiroga presented his initial assessment and diagnosis of the situation to his supervisor, based on three factors: business development, integration, and safety/security of the system.

“Imagine the world in 1923, when aviation was emerging and every country had to find a way to regulate the new industry, but now things move 10 times faster with the internet and social networks making every piece of news and any development available instantly around the world,” Quiroga said. “We have grown my group from a meager four people to a robust team of 21 who are focusing on bringing Safety Management Systems (SMS) concepts to uncrewed aviation in an effort to combine these two very different ways to fly an airplane, into one homogeneous system. The goal is to have a full-blown set of regulations by 2025 with the initial push to change the culture.”

“Imagine the world in 1923, when aviation was emerging and every country had to find a way to regulate the new industry, but now things move 10 times faster with the internet and social networks making every piece of news and any development available instantly around the world,” Quiroga said. “We have grown my group from a meager four people to a robust team of 21 who are focusing on bringing Safety Management Systems (SMS) concepts to uncrewed aviation in an effort to combine these two very different ways to fly an airplane, into one homogeneous system. The goal is to have a full-blown set of regulations by 2025 with the initial push to change the culture.”

The definition of “safe operations” weighs heavily in Quiroga’s mind and occupies a lot of time for his team. This definition is key to how the system will be shaped and the way these operations will be conducted.

“Are traditional crewed operations really safe and reliable today?” Quiroga asked, “Furthermore, what defines safe operations? It’s a valid question. We can safely say that the last 15 years have been the safest of commercial aviation since the creation of a viable airline industry, so in reality the first 105 years of aviation were not so safe or secure. If it took that long to achieve this milestone, how long would it take to reach the same degree of reliability and safety when both crewed and uncrewed aircraft would have to navigate the same skies with a certain dependability? To accomplish this, we will first have to ensure that we have good cellular connectivity with enough redundancy throughout the areas to be flown, that we have enough systems to guarantee in-the-air conflict resolution and a solid UTM system to secure independence, but coordination with ATC. Perhaps at that point we can have full deployment.”

These are the questions and the issues haunting the hundreds of CAAs around the globe as we approach a point where it will be impossible to postpone any longer. In a few weeks, during Commercial UAV Expo 2023 in Las Vegas, we hope to hear from the FAA directly with respect to exactly where are they in the process of authorizing flights beyond visual line of sight in what most believe will be the beginning of a new era in uncrewed aviation.

At some point, we will have the technology we need, the public support and the willingness of elected officials to say, “it’s time.” Only then we will have a true integration of traditional aviation and non-piloted aircraft over the skies of the world for the benefit of all humankind.

Comments