According to the Federal Aviation Authority (FAA)’s Notice of Public Rulemaking (NRPM) on Remote Identification (RID) of Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS), there are over 18,000 law enforcement and security agencies across the United States (U.S.), “many of which would seek access to remote identification information to respond to emerging threats or as part of an investigation.” In fact, the primary driver for RID, which is supposed to undergird all other rules to fully open the skies to commercial UAS, is providing airspace awareness to the FAA, national security agencies, and law enforcement entities. But awareness decoupled from the ability to act does not, in the end, make the public safer or advance the commercial UAS industry. This piece explores the legal gaps that exist for law enforcement that RID brings to the forefront.

Knock and Squawk

Before we dive too deep into enforcement issues, a brief review of the RID NPRM is in order. The NPRM would amend part 89, Remote Identification of Unmanned Aircraft Systems, to title 14, chapter I, subchapter F, Air Traffic and General Operating Rules, to require RID and link those requirements to the registration of all UAS over 0.55 pounds, with limited exceptions. This would permit the FAA and law enforcement agencies to correlate RID and registration data. It would theoretically enable local police, in near real-time, to discern which drones were being flown by the good guys and which by the bad ones.

The effectiveness of the RID proposal is truly theoretical. In reality, the NRPM has some major limiting factors (LIMFACS), including:

- The technology for police to do this (the NRPM mentions a future mobile phone “App”) does not yet exist.

- Even if the tech existed, it’s not clear that law enforcement agencies could afford it.

- UAS registration information does not include an operator’s social security number or date of birth, which are key to unlocking virtually every law enforcement database needed to get a picture of the operator’s biological profile and past criminal history (as was expertly discussed by Travis Moran in a joint article with Christopher Korody in the online publication DroninOn)

- Obtaining an UAS registrant’s telephone number is interesting but irrelevant if someone other than the registrant is operating the aircraft.

- Apparently the only real way to geolocate an operator is via the internet, which can be weak to nonexistent at times. (Think: “Can you hear me now?”)

Putting all of these LIMFACs aside, let’s assume that UAS threat discrimination is actually possible. After (again) theoretically identifying an operator, the NRPM tells us that law enforcement could then make an informed decision regarding the need to take actions to mitigate a perceived security or safety risk. It then goes on to provide three hypothetical law enforcement scenarios, only one of which involves local law enforcement, where RID would enable such action. The relevant hypothetical involves “Lucy” (who has no last name apparently), a deputy county sheriff in Montana who, at an outdoor concert, spots a UAS, uses her RID smartphone app and locates the operator some 90 feet away (yes, it was that easy). During her encounter with the operator, she learns the UAS is unregistered, the operator is clueless, and has him land the vehicle. She then, “takes appropriate local law enforcement action…” What action would that be, exactly?

The 4-1-1 on State Drone Laws

The truth is that when it comes to drones, law enforcement has the responsibility to maintain public safety, but oftentimes lacks the authority to do so. And the NRPM does not provide them any. It can’t, because it’s a federal regulation enforceable by the FAA, who “retains the regulatory and civil enforcement authority and oversight over aviation activities that create hazards and pose threats to the safety of flight in air commerce.” Police are responsible for enforcing local laws, up to and including at the state level. Thus, what a local law enforcement agent can actually do will depend largely on the laws in effect in the local jurisdiction.

The majority of states in the U.S. have drone laws on their books. However, these are not aimed at policing private citizens. Most state laws, ironically, prohibit law enforcement from collecting information or evidence with a UAS, absent a warrant or some other exception, such as to counter a terrorist attack, track a fleeing felon, or prevent danger to life.

Only over the past couple of years have states started creating laws that address private UAS actors. The following is a quick overview of the types of laws that might be implicated in a drone stop (as opposed to traffic stop) scenario, in no particular order. (For a comprehensive list of state drone laws, see Johathan Rupprecht Law, U.S. Drone Laws 2019 at https://jrupprechtlaw.com/drone-laws-state.)

- Too Critically Close for Comfort: Flying over or too close to critical infrastructure, however designated, is a no-no in some states. In the 2016 FAA Reauthorization Act, and re-energized in the 2018 Act, Congress moved to protect critical infrastructure and even went so far as to make it a crime to operate a drone in or on certain grounds (think: White House). However, only the feds have jurisdiction to enforce federal law. Some states already had this type of prohibition on their books. By way of illustration, in 2015, Texas enacted House Bill 1481 listing certain structures as “critical infrastructure” near which privately operated drones cannot operate, the violation of which is a Class B misdemeanor.

- Trespass, Nuisance: Normally, criminal trespass is an offense upon real property (Think: ground). Trespass can also have civil implications (you get sued). Either way, the neighbors will call the cops on UAS operators they believe are interfering with their property. The Uniform Law Commission, or ULC, has proposed a model act for states, the “Tort Law Relating to Drones Act.” This Act, if adopted at the state level, would create a civil cause of action under which intentional flights without landowner consent over land that “causes substantial interference with the use and enjoyment of the property” (further defined by 13 factors) could constitute aerial trespass.

- Peeping Drone, Privacy: Some states have made a special crime for UAS voyeurism. Arkansas and Mississippi have made it a felony for anyone to commit a “Peeping Tom” violation with a drone. Both states added “drones” (or “UAS”) to the list of technologically advanced devices (e.g., a periscope, telescope or binoculars) that one might use to spy on someone in private chambers.

- Save the Animals: Some states prohibit UAS use in game hunting, fishing, and trapping in some manner. Common language includes prohibitions from “using UAS to interfere with or harass an individual who is hunting.” Other criminal provisions for private drone users include prohibitions on spying on hunters or weaponizing drones to facilitate hunting.

- Weaponizer: Speaking of weapons, weaponizing a drone is a common restriction among state drone laws. More than a third of the states have restricted operators from carrying lethal or non-lethal weapons on, or employing weapons from, UAS.

- Drone-as-a-Kicker: Some states have added penalty enhancements onto already existing local criminal codes if a crime is committed with an UAS. One example, Ohio House Bill 228, enhances twenty-three existing crimes such as burglary, endangering aircraft, menacing, voyeurism and vandalism, among others, by creating an additional offense for engaging in those activities, “through use of a drone.”

- No Drone Zone: No fly zones for UAS are a hot topic, and are resulting in litigation (Think: Genesee, County Parks, Michigan). Washington D.C. is a legit “no drone zone,” including the U.S. Capitol, whose police force has its own Capitol Traffic Regulation (CTR). § 16.2.90, Model Rockets and Boats, states, “The use of model rockets, remote or manually-controlled model gliders, model airplanes or unmanned aircrafts, model boats and model cars is prohibited on Capitol Grounds.” CTR violations are subject to arrest, a $300 fine and/or 90 days imprisonment.

Not all states are created equal when it comes to drone crimes. Without something for law enforcement to hang their hats on, they are relegated to calling the FAA.

Responsibility Without Authority

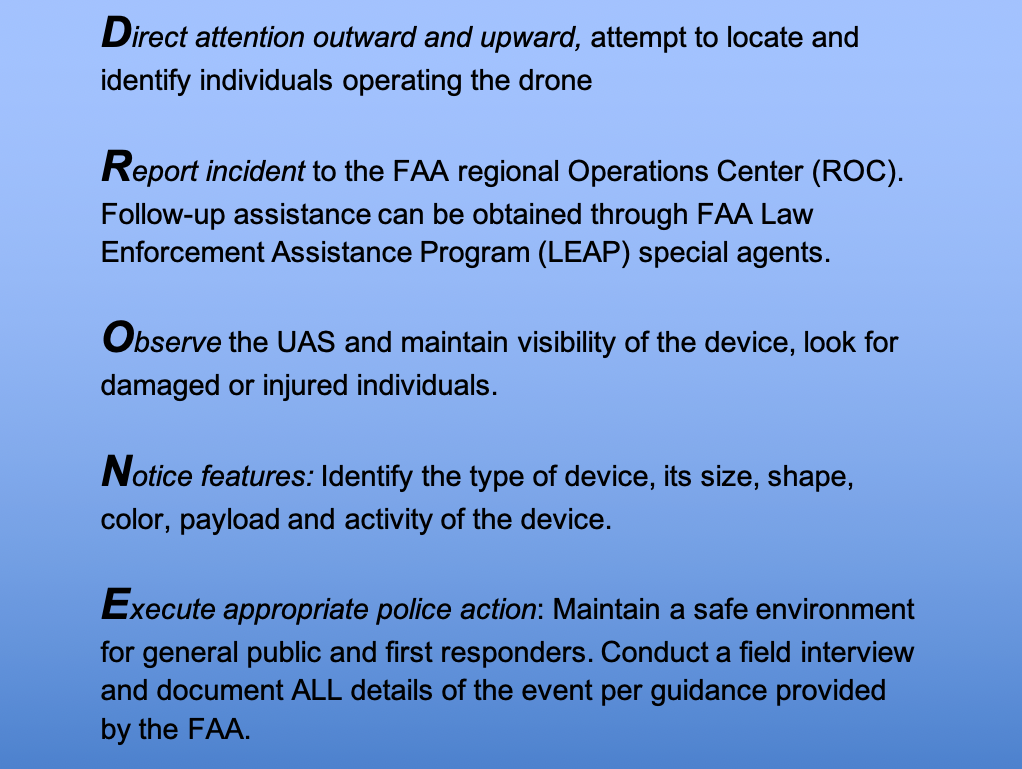

In recognition of the lack of state enforcement mechanisms, the FAA has produced pocket cards, “Basic LE Response - D.R.O.N.E.,” which states:

So, we’re back full circle to “executing appropriate police action.” And when it comes to merely writing a ticket, the police are limited to local and state laws. Beyond that, kinetic action (killing the drone, also referred to as interdiction) for local law enforcement is a no-go. 18 U.S. Code § 32, Destruction of aircraft or aircraft facilities, makes it a crime for anyone to willfully damage, destroy, disable, or wreck any aircraft in the U.S. (But, alas, counter-UAS is a topic for another day.)

So, in the end, even assuming RID is doable, it won’t help our nation’s law enforcement professionals rid the skies of the dumb and dangerous users out there, if they lack relevant local laws they can actually enforce. The good guys—those in the commercial industry—need this lane to be cleared. Until we can deter the would-be clueless and criminal types, UAS integration in the national airspace will continue to elude us. Beyond getting RID right, there remains much more work to be done at the state and local level.

Comments