When talking about drone inspections one will probably associate it with the Construction, Infrastructure, or Energy industries. However, some companies, such as EasyJet, American Airlines, Air New Zealand, and Austrian Airlines, have already run trials with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV) to perform automated inspections of manned aircraft. Today, we’re writing about Mainblades, a startup creating an innovative, quick, and efficient automated solution to reduce aircraft downtime that is now starting to take off.

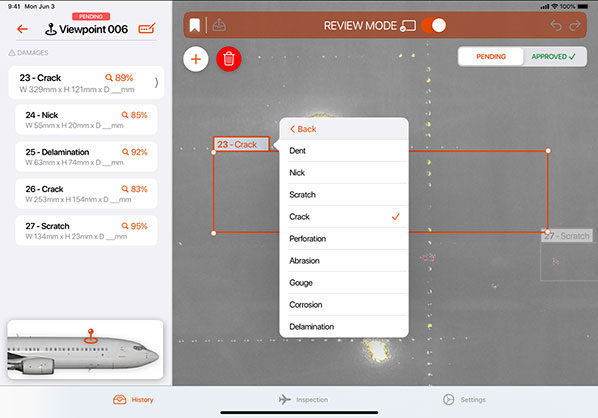

Founded in 2017, Mainblades has been building its software pillars focused on three parts. First is the brains of the drone—the robotic navigation onboard, which is a small module that ties up to a drone and runs various software algorithms (the company’s core capability); second is the iPad application, used to command and control the process; and third is the intelligence in the cloud, which does the automated damage detection and enables further data analyses. Getting the company to a point where the whole inspection pipeline can be executed autonomously and safely around an aircraft was a technical challenge.

“Of the 12 engineers we have working, two of them are hardware engineers focusing on making electronics and our add-to-drone hardware module, and the other 10 are software engineers. This is where our core capabilities are focused on, and where we distinguish ourselves from others,” Dejan Borota, Mainblades CEO, told Commercial UAV News. “Buying a drone and flying around an aircraft or any other object to take pictures of it and compile a report is easy. It is a valid methodology, but it's not good enough to get it certified and scale on a global level. To get it on a level where you can get that certification from an aviation company, and to know where the damage is and how large it is, and that it can fit in the aircraft maintenance procedures – that’s difficult.”

One of the major drivers of automated drone inspections is the predictability of how long an inspection takes. With traditional methods, aviation companies rely on an engineer’s judgment: one person stationed high on the top of an aircraft taking notes, pictures, and making the calls. And then, if, upon review, the pictures aren’t good enough, this would require additional inspections of the aircraft, wasting even more time. With Mainblades’ solution, all aspects of the inspection procedure, from drone flight to report generation, are automated, allowing the ground team to easily analyze and report the status of an aircraft. Other than predictability and reduced inspection time, the drone inspection also prevents human exposure to dangerous situations while still complying with high standards for safety and security.

While Mainblades already developed the hardware a year ago and started communicating and testing with customers early on, getting the big players in aviation to accept it has been a challenge because it is a very certified, regulated, and safety-oriented industry.

“Aviation is all about innovation, but safe innovation and drones are still quite risky,” Borota explained. “I think there's a growing number of both airlines, aircraft manufacturers, but also drone companies, such as Mainblades or companies that build their drones themselves, that are moving more and more into these fields. We're approaching a moment of so-called critical mass where everyone will know about this and be interested so that it cannot be put away anymore. We are not the only ones developing this, and the more we are moving along, the more I appreciate that, because if we were the only ones, chances would be very slim.”

Since 2017, Mainblades has wanted to show that the technology is saving time, money, and reducing safety risks, which is why the company wants to find partners within the aviation industry that are willing to support these efforts and help pave the way for more favorable regulations to expand their operations.

“We are doing it in a hangar, so it's a protected environment, the doors are closed, but still we need to get permission to unlock the drone to enable flying in an airport environment,” said Patrick Morcus, Mainblades CCO. “There is a procedure in place that if you can show [regulators] why you need it, you will get permission for a certain period. It's regulated in a tight way. But this hasn’t slowed us down when we wanted to make a test flight.”

Right now, Mainblades is working inside hangars only, but Borota said they’re looking into making the use case presentable for outdoor applications. For example, performing outdoor inspections would allow the reservation of hangar space for heavy-duty maintenance and scheduled inspections. In the meantime, light inspections could be done in front of the hangar, on parking spots, or at the gate in the future. But, for this to happen, there has to be a significant market request for it. Because planes have to be ready to leave the gate within a short period of time, Borota says it doesn't make sense to fully focus on this application just yet.

“There are two leading regulators: the US FAA and EASA, which is the European equivalent,” Borota said. “It is more complex in Europe because there’s the European one (EASA) and then there are national authorities ‘below’, but they usually just assume EASA rules. From what we’ve seen concerning outdoor flights, even in regulated airspace such as airports, EASA is a bit more in front. It took them a while because they started this journey about six years ago to change the legislation for drones, and last year they published what it would look like. Now, it’s being implemented. It’s still a slow machine, but as of 31 December 2020 forward, you can apply for specific exemptions based on your risk factor and what kind of mitigating measures you are taking to avoid those risks.”

Borota started out studying robotics at the Technical University of Delft, and then joined a startup developing ship cleaning robots, which eventually led him to found Mainblades. Back in 2013, together with his university colleague Jochem Verboom, now Co-Founder and CTO at Mainblades, Borota decided he wanted to run his own startup. Borota got a lead while working in the shipping industry that there was a need for robots to wash aircraft in the aviation industry. While looking into that possibility, they identified a bigger problem with aircraft inspections. They discovered that they were a lengthy and expensive practice. Because of the associated cost, aircraft would usually be shipped to lower paid regions like Eastern Europe and Asia to do the work, which took planes out of active rotation for a longer period of time.

“We started identifying why people were doing this and what was wrong with inspecting here,” Borota told Commercial UAV news. “Then, we came across Mark Terheggen, our third Co-Founder, who was already experimenting with drone inspections, and we found that inspections were done very manually. People drove around the aircraft in carts, and they wouldn’t even take pictures and would only make a note on a piece of paper identifying where there was damage. And that's still primarily how it's done. The technology is coming along, but the process still remains very manual. So, we started to test with a drone whether we could capture good images, and what was needed from the aircraft engineers’ side.”

Initially, Mainblades would fly a drone live-streaming its camera feed to a large screen so engineers could see what was happening in real-time. “Can you fly it there, and can you see that?” engineers asked. “Please, check the tail because I'm supposed to dock it this afternoon and see the antenna.” Even though they were amazed by the technology, engineers found the process too complex, and they didn’t want to fly the drone. That’s why Mainblades started toward building an automated solution.

“We coupled that desire from the market to have a quick solution to view something with our own vision of having robotics, automated machines doing these inspections,” Borota added. “We set out a roadmap and started talking to customers to see how we could get their attention, their support, and validation.”

Due to COVID-19, Mainblades had to postpone test phases planned for May with potential customers. “People weren’t even considering inviting us to do some testing because they were completely focused on the no cash out policies,” Morcus commented. “In the last three to four weeks it started up again.”

According to Borota, there may be a positive side to this, since “every airline is fighting for their existence now. I think this also makes them think about being more efficient with their cash when they start rolling again,” he added. “Before, it was almost like ‘[this solution] is nice, but current methods are fine because we have the people, we have enough firepower and budget to do this.’ But now, everyone is looking at their budgets and they need to find ways to do it better, more efficiently, and cost effectively. They will be looking for solutions like ours that can do it faster and more efficiently to improve their workflows.”

At the end of the interview, we asked Borota and Morcus the one take away they’d like people to understand about Mainblades.

“I know people in the world are waiting a lot for robots “to take over everything”, but it's happening quite slowly because it's very complex,” stated Borota. “A robot, in whatever industry, can do simple tasks 1,000 times better than a human. And it can do that a million times without ever making an error. But doing something as simple as just looking and not bumping into something is extremely complex in our world. If there was a predefined world or space for robots, it could work. In our world, everything is dynamic. We’re making our drones intelligent and making them able to work in quite a complex environment because a hangar is never the same. There are always guys with carts moving around, aircrafts coming in and out, so it's always dynamic. To achieve a technical status where you can apply your product in the real world, in such a technical environment, it's great. Automation is actually boring when it works; but when it does, it's really cool. We're on the verge of doing that, and it’s really exciting because we're going to do this boring thing in a really exciting environment. And, if it works, it's going to be very, very impressive.”

“Today, when looking outside the gate to see the aircraft, you will see an aircraft engineer inspecting it,” added Morcus. “In five years, you will see a drone flying around it.”

.jpg.small.400x400.jpg)

Comments