True Story

It is nighttime. The dogs are barking in the front field as I take the homebuilt drone out and place it in the driveway—a big one, a homebuilt 2 Kg (4.5 lbs) quadcopter with a four-foot prop-span. In the living room everyone settles in front of the big screen TV. With controls in hand, I turn on the headlight, select the wide-angle starlight camera, hover at 15 feet and then guide the craft down the driveway, through the slot between the fence and power line and down the field to the pole barn. Hovering at 10 feet at the opening of the pole barn, I switch to the close-up camera.

“Lola has dropped her kids!” My wife and daughter exclaim in unison.

Lola is one of the goats in our herd. In an instant, wife and daughter are out the door making the 10-minute trek to check on Lola and family. As I land the drone back at the house, the phone rings.

"She had three. One is fine, one is dead, and one is alive but not breathing.” She says with anguish in her voice, “Please bring the suction bulb out here as fast as you can, perhaps we can save her."

Instead of jumping on my truck, I strap the bulb on the drone and fly it out to them in less than a minute. After it lands and disarms, I watched my daughter walk out to the drone and retrieve the bulb from the craft. As I fly the drone home, I’m aware that, licensed pilot or not, I just committed multiple Federal crimes without bothering or hurting anyone, or even leaving my own property. When my wife and daughter arrive carrying the rescued goat, I wonder: What's wrong with this picture? Does the FAA really own all of the airspace between the dirt and the heavens, even on private property?

UAV Traffic Management and the FAA Remote ID Notice of Proposed Rulemaking

With the commenting period closed for the Remote ID Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (RID NPRM) and after more than 50,000 comments officially submitted to the FAA, the time has come for some reflection.

The plan has received scathing reviews and rebukes from hobbyists and certain commercial drone operators. They allege it’s too far-reaching and that many of the existing model aircraft and drones can't meet the requirements. Some organizations had gone so far as to imply that the RID NPRM is designed to phase-out all homebuilt UAS in favor of approved, tamper proof, factory-built craft.

Membership organizations such as the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association, the Experimental Aircraft Association, and the Academy of Model Aeronautics not only submitted official comments to the FAA but published guidelines to its members on how to properly and respectfully comment.

The level of interest that the RID NPRM has created around the industry might not be unprecedented, but it certainly created some heated opinions that compelled all these organizations to plead with their members to be civil.

According to some of the specific comments submitted to the FAA from these members, the proposed rule seems to favor large organizations, such as delivery behemoths FEDEX, UPS and Amazon.com, that can afford to use more expensive drones that meet the remote ID requirements.

The area of aviation that seems to be more affected by the NPRM is remote controlled, home-built devices, such as model aircraft and multicopters. This is particularly true in rural areas where farmers have found a multitude of useful applications for drones on their property.

We recently had contact with one such individual; his name is Phillip (Phil) Smith and he’s a retired private pilot and Part 107 active pilot. Currently, Phil is helping his son Reuben tend to his goat farm with a home-built quadcopter with a 4-ft wingspan that weighs about 4.5 lbs.

Phil has an interesting aviation background and one that gives him amazing credibility when it comes to new regulations. He’s held a private pilot certificate since 1967 and an amateur radio license since 1962. As a FAA certified repairman, Phil serviced civilian transponders, DME, and radar for 13 years; he also maintained the first functional Microwave Landing System in the nation at the Richmond, VA airport.

In March of 2019 Phil received his Part 107 sUAS certificate and went into designing and building quadcopter drones specifically for farm use. Phil is also involved with a rural school district establishing a drone apprenticeship class for their STEM program.

The mixture of aviation background and farm knowledge allows Phil to be uniquely positioned to understand the implications of RID NPRM and to submit comments to the FAA.

“Drones have proven to be incredibly useful as a farm tool. They can be used to herd and monitor livestock, chase predators, chase deer away from crops, survey fence lines, deliver vet supplies and tools within farm boundaries, check water and feed levels, and certainly many tasks we have yet to identify,” Phil explained enthusiastically. “Our experience is that these activities rarely exceed 50ft AGL, and they never extend beyond the farm property boundary. We have set the RTL (Return to Launch) altitude on our craft to 100ft (just enough to clear trees and power lines). The safest and most effective way to accomplish these tasks is with the pilot wearing an FPV hood. In fact, flying solely by visual line of sight is quite dangerous. There is no benefit or justification for a spotter except for delivering things within the farm boundary, in which case the spotter is usually the one receiving the delivery, and they are in communication with the remote pilot.”

It’s important to note that all of these tasks are accomplished at very low altitude without leaving the boundaries of the farm’s private property.

“It could be argued that these activities take place within private airspace, and that they are not legitimately within FAA jurisdiction,” continued Phil. “Viewed from that perspective, the FAA prohibitions of such activities in the Part 107 rules are an unconstitutional taking of private property airspace enjoyment for no legitimate purpose and without compensation. We are committed to following FAA regulations, but the Part 107 rules present needless obstacles to fully benefiting from drone capabilities. Most of the drone activities desired on a farm require some BVLOS operation within the farm boundaries where a spotter is neither available nor necessary. Furthermore, a substantial portion of the need for drone BVLOS flight occurs during hours of darkness. Having applied for a Part 107 waiver for these operations and having been denied, it has become apparent that the FAA has no intention of granting such relief. The farmer is then left with the option of forgoing many of the great benefits of drone use or violating Federal law.”

So, what can people who are looking to take advantage of drones on their property do?

“Clearly, a layered approach would be in everybody’s interest,” elaborated Phil. “What we need is a plan that keeps everyone out of each other’s way. Overlaid on the safety issue is the desire of national security and law enforcement groups to know where every airborne object is, who is flying it, why, and where the remote pilots are. Expecting bad actors to broadcast their location and their craft’s location is a fool’s errand. If law enforcement knows where their own craft are because they are RID equipped, everybody else is a bad actor.”

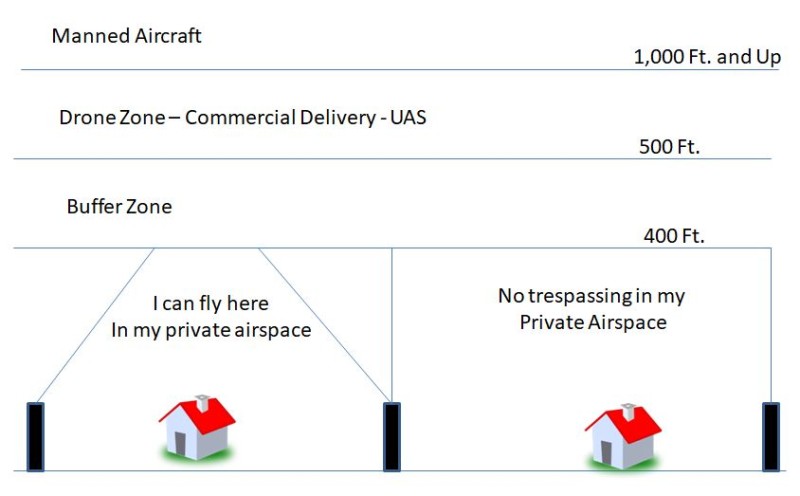

And here comes the innovative part, the creation of Private Airspace (PAS). Phil has come up with an ingenious idea about creating a flying zone in which landowners can operate their home-built crafts over their property following certain rules.

Private Airspace Concept

PAS takes into account the right of neighbors to privacy and the ceiling limitations that would allow distribution drones, air taxis and commercial airliners to operate without danger and interference from low-level operations.

“It may be worth pointing out that this proposal is a starting point, mainly applicable to rural areas. The situation in more built-up locations will necessarily be more complicated,” Phil explained. “For example, the airspaces between two buildings should divide at the midpoint between the two building surfaces. This gets messy if the property boundaries are not symmetrically arranged. Also, since the proposal creates a great multiplicity of jurisdictions that are not universally prepared to write airspace legislation, there might be need for a National Airspace Code that writes policies that can simply be referenced as needed.”

In any case, RID NPRM has created a national conversation about the rights of certain individuals and groups that are unevenly affected by the introduction of UAV’s in the NAS and the absolute need to maintain a safe flying environment for all.

For a more in-depth discussion and definition of Private Airspace, you can access Phil's entire submitted proposal to the FAA here.

Comments