Eagle Eye Imaging LLC opened its doors in Woodbine, Maryland with the goal of using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, or drones, to provide local growers with faster and more affordable answers to many of their most common field condition questions. The overall goal is to help growers quantify their unknowns, reduce production risk and maximizing harvest yield. Since 2016, the firm has delivered reports derived from drone imagery to farmers in Maryland, Pennsylvania and Delaware.

“Growers don’t have time to become remote sensing experts,” said David Kivioja, Eagle Eye Imaging President. “Our business model is to capture the imagery and then do the analysis, so we can hand them a map or report that shows exactly where the problems are in their fields.”

At the outset, the firm’s agricultural mapping work focused primarily on pinpointing crop stress in corn and soybean fields. This application of remote sensed data is not new, having been performed for decades with manned aircraft and even satellite imagery. The difference now is that the significantly lower operating costs of drones makes this process practical in smaller fields and at multiple times of the season. Drone technology enables on-demand imagery not available with the more traditional methods.

Eagle Eye Imaging purchased the Smarter Farming Package from DJI, a major provider of recreational and professional drone systems. The package included the DJI Matrice 100 quadcopter, Precision Hawk DataMapper mapping software, and two digital imaging cameras – one capturing data in the visible (Red Green Blue) spectrum and the other in the Near Infrared. These cameras do not have zoom lenses, so the spatial resolution of acquired imagery is controlled with flight altitude.

For a typical flight to map crop stress in corn fields, the firm flies the Matrice 100 at an altitude of 250-300 feet above ground level capturing imagery at 1.5-inch resolution. From these images, Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) maps are generated with the DataMapper package. In shades of red, NDVI differentiates healthy crops from stressed ones. In a matter of minutes, Kivioja can analyze the colorized maps manually to create a report giving precise latitude-longitude coordinates for stressed conditions.

“The NDVI reports are pre-survey guides for the agronomists to use in quickly finding problems in the field,” said Kivioja. “Field surveys by agronomists are expensive and traditionally performed on foot; knowing precisely where to look for trouble translates into an enormous cost savings for the grower.”

The challenge for Eagle Eye Imaging came when a grower asked the firm to use drone technology to supplement another activity traditionally performed on foot – crop counts. Not usually requiring the skills of an agronomist, this annual process involves a field hand walking the rows and counting corn stalks or bean sprouts. Performed over small sections of a given field, the counts are extrapolated for the entire crop.

“This can be an expensive and time-consuming process that yields inaccurate results due to human counting errors and extrapolation,” said Kivioja.

He knew crop counting was possible with drone imagery, but it too would be a manual process that would introduce errors. As a test in late 2019, Kivioja visually counted individual corn stalks in drone images. As expected, the procedure was tedious and took hours just to tally plants in one section of a large field. Extrapolating results was still required. This method would offer no cost savings to the grower because it required so much time in the image analysis lab.

Counting corn stalks in imagery was feasible, but Kivioja realized he had to automate the workflow to make it cost-effective.

A drone mapping firm in Maryland has reduced the time it once took to count plants and identify noxious weeds in corn field images from hours to minutes by applying Artificial Intelligence technology in its workflow. Having fine-tuned the drone-assisted crop counts and weed detection methods into financially viable automated processes, the firm will offer the high-tech mapping solutions as commercial offerings to clients in the 2020 growing season.

Leveraging Artificial Intelligence

The Eagle Eye Imaging owner believed machine learning technology might be the answer. In this process, artificial intelligence algorithms teach the computer to recognize features or objects, such as corn stalks, in digital imagery. Much more exact than the naked eye, this method would take just minutes and count every single plant in a field, eliminating the inaccuracies of extrapolation.

After searching the Internet for AI services, Kivioja chose an online platform developed by Picterra of Lausanne, Switzerland. Rather than requiring the Eagle Eye Imaging to buy new software and hardware, it put machine learning algorithms and supercomputing power at his disposal in the cloud for a subscription fee. Another advantage was that it allowed the mapping firm to create its own custom machine learning model for corn counts and apply it repeatedly, keeping better control of costs.

“We have broken down the barriers to accessing artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies, so that experts like David Kivioja can apply vertical-market knowledge and experience to build their own customized training models,” said Frank de Morsier, Picterra CTO and Co-Founder.

Kivioja explained that creating the training model was easy: “You just draw polygons [on the imagery onscreen] around examples of what corn stalks are and are not.”

The accuracy of the model could be enhanced by including a variety of stalk sizes and leaf configurations in the sample groups. To teach the model what wasn’t a corn stalk, he drew polygons around bare dirt, grassy areas, and an irrigation ditch. Developing the training model with the Picterra algorithms required inputs of only 12-15 sample features, a fraction of what other AI processes involve.

Kivioja experimented with several factors and found the most accurate corn counts came from drone imagery with half-inch spatial resolution acquired at an altitude of 150 feet at the V2 stage of corn plant growth. Image acquisition had to occur before the leaves of adjacent stalks touched each other. Once the model was created, it could be applied in several corn fields with the addition of one or two new calibration samples to account for different plant varieties or planting patterns.

“It took just two hours to create our first model and then a few minutes to run it [on imagery of one corn field],” said Kivioja. “The results were very accurate.”

Eagle Eye Imaging knew it had a cost-effective new service to offer the growers, but the firm believed the same AI process could be applied to an even more challenging problem – weed identification.

Finding Weeds in Corn

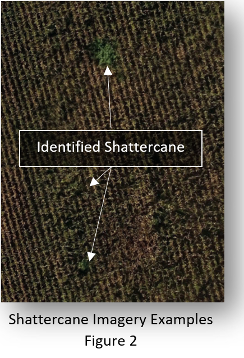

In the Mid-Atlantic region where Eagle Eye Imaging works, a weed called shattercane poses a serious problem to corn growers. Not only does it crowd out corn stalks, this weed can be hazardous to livestock if it mixes in with feeding corn during the harvest. In addition, if harvested, weed seeds can be transferred to other fields by harvesting equipment. For this reason, most growers try to eradicate it long before their combines enter the field to gather the crop.

In the Mid-Atlantic region where Eagle Eye Imaging works, a weed called shattercane poses a serious problem to corn growers. Not only does it crowd out corn stalks, this weed can be hazardous to livestock if it mixes in with feeding corn during the harvest. In addition, if harvested, weed seeds can be transferred to other fields by harvesting equipment. For this reason, most growers try to eradicate it long before their combines enter the field to gather the crop.

“What makes the shattercane hard to eliminate is that it changes genetically so fast that it can quickly develop a resistance to a specific herbicide,” said Kivioja. “Spot treating the weeds with herbicide may or may not work. Most growers prefer to cut the weeds out.”

Shattercane is a leafy plant that resembles corn and grows just as tall at maturity. The main difference is the weed has berries but no cobs. Not recognizing it during harvest, farmers have been known to run right over it with their combines. Kivioja had tried detecting the weeds in drone images with the naked eye, but the results were mixed. And just like the manual counting attempt, the process had been impractically time consuming.

Working again in the Picterra platform, he modified the corn count training model that had been created earlier. This time, the model was taught to look for shattercane and not for corn. The model was applied to V2 drone imagery with half-inch resolution.

“The results were amazing,” said Kivioja. “With a high degree of accuracy, the Picterra AI model differentiated individual shattercane weeds from corn stalks in the imagery. This would have taken hours and been much less accurate with the naked eye.”

Most importantly, the weed mapping was accomplished early enough in the growing season that the grower would be able to use the precise location information to eradicate the noxious plants before they harmed the rest of the corn crop. And for Eagle Eye Imaging, the low cost of using the online Picterra platform and reusing its training models translated into a financially viable service that is worthwhile to growers.

The Maryland drone mapping firm will roll out the AI-assisted crop counting and weed detection services to corn growers this season.

Comments