On December 17, 2025, we celebrated the 122nd anniversary of the Wright Brothers' flight, and the start of aviation as we know it. One of the most distinctive features of this established industry is the proliferation of membership organizations. For decades, these organizations have lobbied in Washington to protect the rights of its members to fly, and now they face the prospect of thousands of non-piloted, or remotely piloted aircraft (RPAs) ‘invading’ the National Airspace System (NAS).

The FAA’s notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) for Part 108 represents the most ambitious attempt to date to normalize BVLOS drone operations in the United States. Published in 2025, the NPRM outlines a performance‑based framework intended to move BVLOS flights out of a waiver‑only regime and into a scalable system supporting routine commercial and civic operations. The rule would enable low‑altitude flights beyond the visual range of the operator for activities such as package delivery, infrastructure inspection, agriculture, and public safety missions, supported by new concepts like third‑party services and UAS traffic management (UTM).

To achieve this, the FAA proposes a two‑tier structure. Lower‑risk operations could be authorized via operating permits, while more complex, higher‑risk operations would require operating certificates with greater organizational obligations. In the agency’s framing, Part 108 is a natural next step in integrating UAS into the NAS, mandated by Congress and informed by prior ARC recommendations and years of waiver experience. Yet, the proposal has triggered intense scrutiny from these aviation membership organizations, which broadly support the goal of integration but question how the NPRM distributes risk and responsibility.

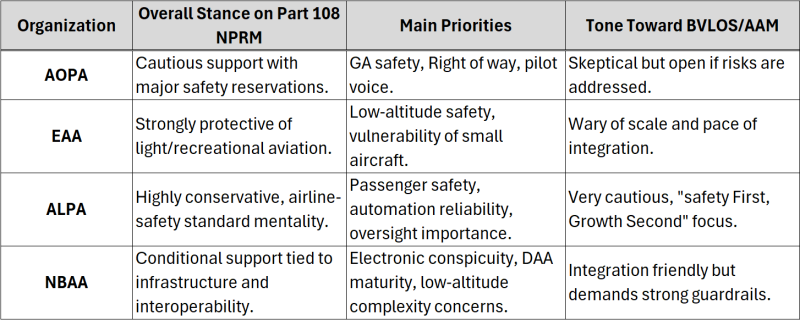

This article compares how four major players-namely AOPA, EAA, ALPA, and NBAA-view the Part 108 NPRM, highlighting both converging themes and important nuances.

Shared ground: Support the goal, question the path

Despite representing different constituencies, these organizations share several core perspectives.

First, all four broadly accept that BVLOS operations and, eventually, air taxi or advanced air mobility (AAM) services are coming. They are not arguing to halt UAS integration; rather, they are focused on how it is done, at what pace, and with what safeguards. Their comments tend to acknowledge that clearer, scalable rules are preferable to a patchwork of waivers and exemptions.

Second, they converge on the concern that the NPRM leans heavily on automation, especially detect‑and‑avoid (DAA) and highly automated flight management, without a fully demonstrated safety performance. The proposal emphasizes “normalizing” BVLOS through performance‑based standards and simplified user interfaces, where human operators issue high‑level commands rather than manually flying the aircraft. For many crewed‑aviation stakeholders, that shift raises questions about the reliability, certification, and oversight of the underlying technologies.

Third, they share a discomfort with any change that would erode the long‑standing priority of crewed aircraft in right‑of‑way rules. Even where the NPRM contemplates carefully bounded circumstances in which drones might be treated differently, membership organizations consistently frame crewed aviation, especially aircraft carrying people, as the party that should never bear elevated midair collision risk because of new actors in the NAS.

AOPA: Guardian of General Aviation Pilots

The Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA) approaches Part 108 primarily through the lens of everyday general aviation operations. Its core focus is the safety and workload of pilots flying small aircraft in mixed environments where drones and air taxis may be present.

AOPA’s concerns cluster around four themes:

- Risk distribution: The association fears that largescale BVLOS operations could increase collision risk for GA without commensurate safety margins, particularly in low‑altitude airspace where GA routinely operates.

- Right‑of‑way stability: AOPA resists any interpretation of the rule that could, in practice, grant automated systems’ priority over crewed aircraft, arguing that this would invert historic NAS safety logic.

- Operator qualifications: It questions whether proposed training and certification expectations for BVLOS operators are aligned with the operational privileges Part 108 would grant.

- Voice in rulemaking: AOPA has repeatedly emphasized that pilots must have a meaningful role in shaping integration policies, not just reacting to industry‑driven frameworks.

Overall, AOPA lands in a position of cautious support: open to BVLOS expansion, but only if the rule more clearly protects general aviation pilots from becoming the ‘absorbers’ of residual risk.

EAA: Protecting the Most Vulnerable Aircraft

The Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA) shares many of AOPA’s concerns but places particular emphasis on the vulnerability of light, experimental, and recreational aircraft. These aircraft often operate at lower altitudes, at slower speeds, and without the same onboard systems that larger businesses or airline aircraft carry.

EAA’s critique of Part 108 centers on:

- Low‑altitude realism: It argues that the NPRM underestimates the density and diversity of existing operations below 400 feet, where many recreational and experimental flights occur.

- Collision consequences: In any encounter between a small, lightly built aircraft and a BVLOS drone of appreciable mass, the outcome is especially consequential for the crewed aircraft.

- Access and culture: EAA is sensitive to the broader cultural question: whether rulemaking will gradually squeeze out experimental and recreational aviation in favor of highly automated commercial networks.

EAA’s stance is therefore somewhat more defensive: it is not only concerned about safety, but also about preserving the character and accessibility of grassroots aviation as the NAS evolves.

ALPA: Airline‑Grade Safety Expectations

The Air Line Pilots Association (ALPA) evaluates Part 108 through the prism of airline operations and passenger safety. For ALPA, any rule that permits unmanned aircraft to share airspace, horizontally or vertically, with large passenger jets must meet standards comparable to those applied to airline systems.

ALPA’s reservations focus on:

- Automation reliability: The NPRM’s emphasis on highly automated, pilot‑out‑of‑the‑loop control raises the question of how DAA and associated systems are tested, certified, and monitored at scale.

- Systemic safety case: ALPA looks for a robust, system‑level safety case that considers failure modes, human–automation interaction, cybersecurity, and integration with air traffic control.

- Regulatory symmetry: The union questions whether UAS operators will face safety management, reporting, and oversight expectations commensurate with the risks they introduce, especially in busy terminal environments.

Consequently, ALPA adopts the most conservative posture of the four organizations: while not opposed to BVLOS in principle, it is inclined to delay normalization until technologies and oversight frameworks reach airline‑grade maturity.

NBAA: Integration with Infrastructure and Interoperability

The National Business Aviation Association (NBAA) is somewhat more integration‑forward, but ties its support to specific conditions around infrastructure, interoperability, and information sharing.

NBAA’s perspective highlights:

- Electronic conspicuity: The association stresses that all aircraft (crewed and uncrewed) should broadcast their position electronically to enable mutual awareness and reduce dependence on visual acquisition alone. It sees universal electronic conspicuity as a prerequisite to safely mixing BVLOS drones with business aviation traffic, especially at low altitudes and near airports.

- Interoperability: NBAA is concerned that the NPRM does not fully resolve how UAS, helicopters, business jets, and future AAM vehicles will interoperate in both controlled and uncontrolled airspace.

- Low‑altitude complexity: Like other groups, NBAA believes the FAA underestimates the complexity of low‑altitude airspace, where helicopters, air ambulance operations, and business aircraft already operate in demanding environments.

Relative to other organizations, NBAA is more explicit in treating Part 108 as an opportunity to build a modern, information‑rich infrastructure for all airspace users, provided that the foundational pieces, such as electronic conspicuity and robust DAA, are in place before privileges are expanded.

A Complex Consensus: Integration, But Not at Any Cost

Taken together, the positions of AOPA, EAA, ALPA, and NBAA do not form a simple “for or against” split on Part 108. Instead, they reveal a layered consensus: BVLOS and AAM integration are acceptable only if they do not dilute the safety protections and access that existing NAS users currently enjoy.

The FAA’s challenge is to reconcile its mandate to enable new operations, using performance‑based, scalable rules, with these organizations’ insistence that the risk calculus must not shift silently onto crewed aviation. How the agency adjusts Part 108 in its final form will signal not only the future of drones and air taxis, but also the degree to which traditional aviation communities feel they remain full partners in shaping that future.

Comments