As the Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) sector moves from concept to commercial reality, the most consequential bottleneck is not battery chemistry, noise reduction, or public acceptance; it's certification. The FAA's approach to approving next‑generation aircraft will determine which companies reach the market first, which business models survive, and how quickly the United States can field a new class of air transportation. If regulators impose standards equivalent to those applied to commercial airliners, the industry’s financial viability collapses. If the federal agency relaxes requirements to something resembling automotive standards, safety erodes and public trust evaporates. The answer, inevitably, lies somewhere in between — and today, we are comparing three companies that are actively testing the boundaries of that middle ground.

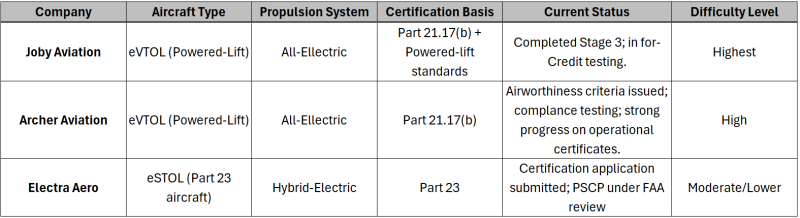

Joby Aviation, Archer Aviation, and Electra Aero are all pursuing FAA certification, though they are not following the same path. Their aircraft differ in architecture, propulsion, and operational intent, and the FAA has not created a single, unified certification framework for AAM. Instead, each company is navigating a different regulatory channel, revealing how the agency is adapting existing rules to accommodate novel technologies. Understanding these differences is essential for anyone tracking the future of AAM.

Joby Aviation is the furthest along in certifying an electric vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) aircraft, and its progress has effectively made it the FAA’s reference case for powered‑lift vehicles. Because no existing category fully captures the characteristics of an eVTOL, Joby is certifying under Part 21.17(b), a provision that allows the FAA to assemble a custom certification basis when an aircraft does not fit neatly into the airplane or rotorcraft categories. This is a demanding path, requiring the company to meet a mosaic of standards drawn from multiple parts of the regulations, supplemented by new powered‑lift guidance the FAA has been developing in parallel.

Joby has now completed Stage 3 of the FAA’s five‑stage type certification process, a milestone that signals the agency has accepted all of the company’s certification plans. These plans cover everything from structural loads and flight controls to cybersecurity, human factors, and noise. With Stage 3 complete, Joby has entered Stage 4, the for‑credit testing phase. This is where every component, subsystem, and flight behavior is tested under FAA oversight, and where compliance findings begin to accumulate. It is the most labor‑intensive stage of certification, but also the clearest indicator that an aircraft is approaching approval. Joby has also secured a Part 145 Repair Station Certificate, allowing it to perform maintenance on its aircraft — a step that positions the company not only as a manufacturer but as a future operator.

Archer Aviation is pursuing a similar certification basis for its Midnight eVTOL, also under Part 21.17(b). The aircraft is broadly comparable to Joby’s in mission and configuration, and Archer is subject to the same powered‑lift regulatory framework. However, Archer’s certification timeline is not as advanced. The FAA has issued the final airworthiness criteria for Midnight, which defines the standards the aircraft must meet, and Archer is now in the compliance and testing phase. But it has not yet reached the for‑credit testing stage that Joby has entered.

Where Archer stands out is not in aircraft certification but rather in operational readiness. The company has already secured three of the four certificates required to operate an air taxi service: a Part 135 Air Carrier Certificate, which authorizes commercial operations; a Part 145 Repair Certificate, which allows maintenance activities; and a Part 141 Pilot Training Certificate, which enables Archer to train its own pilots. This means that while the aircraft itself is not as far along in the certification process as Joby’s, the company is building the operational ecosystem around it at an impressive pace. This is a strategic choice. By preparing the airline‑like infrastructure early, Archer positions itself to scale quickly once the aircraft receives its type certificate.

A crucial distinction among these three aircraft is their choice of propulsion architecture, which carries significant certification and operational implications. Joby and Archer have committed to fully electric systems, a decision that aligns with the long‑term vision of zero‑emission AAM but introduces near‑term challenges around battery energy density, thermal management, and cycle life. These constraints shape not only aircraft performance but also the certification burden, because the FAA must evaluate new electric‑propulsion safety cases, high‑voltage architectures, and battery containment standards that have limited precedent in aviation. Electra, by contrast, has opted for a hybrid‑electric configuration that uses a small turbine generator to supply power to the distributed electric motors.

This approach dramatically reduces dependence on battery storage, enabling longer range, higher payload, and more predictable performance across temperature extremes. It also simplifies certification by allowing Electra to rely on well‑established turbine safety standards while introducing electric propulsion incrementally rather than all at once. In effect, Joby and Archer are pushing the regulatory frontier of all‑electric aviation, while Electra is threading a pragmatic middle path that leverages existing certification frameworks and mitigates the operational limitations of current battery technology.

Electra Aero represents a very different branch of the AAM tree. Unlike Joby and Archer, Electra is not building an eVTOL. Its EL9 Ultra Short is a hybrid‑electric short takeoff and landing aircraft, an eSTOL design that uses blown‑lift technology to achieve extremely short runway requirements. Because it takes off and lands conventionally — albeit in very small spaces — the aircraft fits comfortably within the FAA’s existing Part 23 small airplane category. This is a major advantage. Part 23 is a mature, well‑understood certification framework with decades of precedent, and the FAA does not need to create new standards or interpret novel architectures to evaluate Electra’s aircraft.

Electra has formally applied for Part 23 type certification, submitting the required FAA Form 8110‑12, its Project Specific Certification Plan, and its Aircraft Specification. This moves the company from the FAA’s Emerging Technology division into the formal certification pipeline. While Electra is later in the process than Joby or Archer, its path is arguably more predictable. The technical risks are lower, the regulatory uncertainties fewer, and the certification workload more conventional. For these reasons, some analysts believe Electra may reach certification sooner than many eVTOL developers, even though its aircraft is not as far along today.

Taken together, these three certification efforts illustrate the FAA’s evolving approach to AAM. Rather than creating a single regulatory regime for all advanced aircraft, the agency is adapting existing frameworks where possible and developing new standards only where necessary. Powered‑lift eVTOLs like those from Joby and Archer require bespoke certification bases and new operational rules, including special federal aviation regulations (SFARs) that define pilot qualifications and operating limitations. eSTOL aircraft like Electra’s, by contrast, can be certified under traditional airplane rules, with only incremental adjustments for hybrid‑electric propulsion.

This divergence has strategic implications. Joby is closest to type certification and is shaping the FAA’s understanding of powered‑lift aircraft. Archer is building the operational infrastructure that will support early air taxi networks. Electra is pursuing a lower‑risk certification path that could enable regional mobility services to enter the market sooner than urban eVTOL operations. Each company is betting on a different combination of technology, regulation, and market timing.

What unites them is the recognition that certification is the true gatekeeper of AAM. The companies that understand the regulatory landscape — and can navigate it with discipline and foresight — will define the first generation of advanced air mobility. The FAA, for its part, is walking a tightrope: ensuring safety without stifling innovation and enabling a new industry without compromising the principles that have made U.S. aviation the safest in the world.

.jpg.small.400x400.jpg)

Comments