For almost ten years now, we have been hearing about the promise of "new aviation," something that would vaguely resemble the 120-year-old technology that has defined traditional aviation since the Wright Brothers' flight in 1903. This revolutionary way to reach for the skies - eVTOL - has been based on two fundamental principles. First, the "e" in its name defines the powerplant, as it is purely electric as opposed to burning fossil fuels, as with traditional aviation.

The second part of the term is where things get a bit more complicated. VTOL, or vertical takeoff and landing, means that the aircraft can start and end each mission like a helicopter but perform in cruise as a fixed-wing platform in a configuration where fighting gravity becomes a shared task between the engines and the wing. Initially, the industry called this technology Urban Air Mobility (UAM), but in March of 2020, NASA labeled the nascent industry as Advanced Air Mobility (AAM), a term that is widely accepted today as a better and more inclusive fit than UAM.

For almost five generations, humans have surrendered enormous amounts of land and valuable real estate to the reality of airports. These are large and complex extensions of land that can accommodate the enormous aircraft that require thousands of feet of runway to take to the skies, and then an equal amount of distance to dissipate all that accumulated kinetic energy.

The adoption of the hub-and-spoke scheme after the U.S. airline industry was deregulated in 1978 created the need for behemoth airports such as Dallas-Fort Worth, Atlanta International, and many others. The deregulation allowed airlines to freely organize their routes, making the hub-and-spoke system, which concentrates flights at central airports to serve a large number of destinations, the dominant strategy for most major carriers. This strategy had the unintended consequence of creating a large concentration of flights in and out of large urban centers.

There is no doubt that this transportation strategy has been beneficial to the airline industry and has contributed to the affordability of air travel. However, it has simultaneously created a system that has reached its limits in terms of safety and the ability of human air traffic controllers (ATC) to handle the volume, consistency, and growing number of flights per hour.

This is where the promise of eVTOL captured the imagination of entrepreneurs and investors alike. Companies such as Joby Aviation, Archer Aviation, Electra Aero, and the now-defunct Lilium came up with innovative designs using electricity as their power source and a sales pitch that included a small ground infrastructure on which to operate.

Unfortunately, all of the above-mentioned aircraft are small, carrying four to six passengers, and can only operate on short flights of around 50 to 150 miles. Electra Aero is the notable exception to this, as they advertise flights up to 400 miles with nine passengers aboard.

This is where we arrive at the issue of ROI for AAM companies. In March of 2022, the air taxi company GlobeAir signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with Lillium to expand its offerings to cover the "last mile" of every air traveler.

GlobeAir is a private jet charter company based in Austria, offering on-demand charter flights at competitive rates all over Europe. Founded in 2007, they offer services all around Europe, flying to over 984 airports on the continent with an advertised 15-minute boarding time. They have grown steadily since their founding and currently operate a fleet of about 20 Citation Mustang (C510) jets. By all commercial aviation standards, GlobeAir is a successful company with a solid revenue stream and a bright future. However, the alliance with Lillium was short-lived, and the reason should be carefully analyzed by this new industry in love with technology and reluctant to deal with the reality of the aviation business.

In a recent article in Aviation Week, writer Angus Batey interviewed the founder and CEO of GlobeAir, Mr. Bernhard Fragner, and the comments from a seasoned aviation executive should be cause for alarm.

According to Mr. Fragner, there is “no business case” to support wide-scale adoption of this emergent class of aircraft. After struggling with the Lillium technology and the details of its adoption, the MOU became obsolete after the latest insolvency of the eVTOL German company in early 2025.

The main reason for Mr. Fragner’s trepidations about Lillium was their battery technology. We all suspected that at one point, something so new and different would encounter problems with scalability, but GlobeAir’s experience trying to merge its operations with the eVTOL aircraft gave us a definite clue.

All airports around the world are equipped to deal with gasoline - either Jet-A1, AVGAS, or both - but none have recharging capabilities for large eVTOL batteries, so investors had to be convinced to put money upfront to create the ground infrastructure permitting such operations as ultra-fast charging or battery swaps.

“When they came up with the battery performance and the hourly costs to replace the battery, it’s insane,” elaborated Mr. Fragner, who could not find anyone on the continent willing to pony up the cash to create the infrastructure for the new technology.

Most people are not aware that the aviation business is a low-margin, cost-intensive business with lots of competition and high liability insurance premiums, so anything that is slightly out of the ordinary will be treated as ‘experimental’ and therefore commercially unviable.

Lillium is no longer in business, and we should not invest any more time ruminating over what happened. That being said, the lesson should be learned, and we can focus on the example of Electra Aero, an eVTOL technology that does not rely purely on electricity.

Electra Aero’s hybrid-electric propulsion system uses a combination of a turbogenerator and battery packs to power the aircraft's electric motors. The turbogenerator is sized for cruise, while the battery boosts power for takeoff and landing. This way, the turbogenerator can be small and always operates at its most efficient operating point. This reduces fuel burn and lowers maintenance costs.

We all seem to agree that eliminating 100 percent of fossil fuels is good for the planet, but what’s wrong with eliminating 90 percent? Why is that not a great starting point?

According to Electra Aero, operators can choose to charge the battery in flight via the turbogenerator or recharge on the ground where charging infrastructure is available. However, charging infrastructure is not required. The turbogenerator supports up to 100 percent sustainable aviation fuels and long-term future use of eFuels or hydrogen for zero-emissions flight.

This is clearly the way to start. The current state of the battery chemistry is unable to sustain a consistent business model, given current regulations.

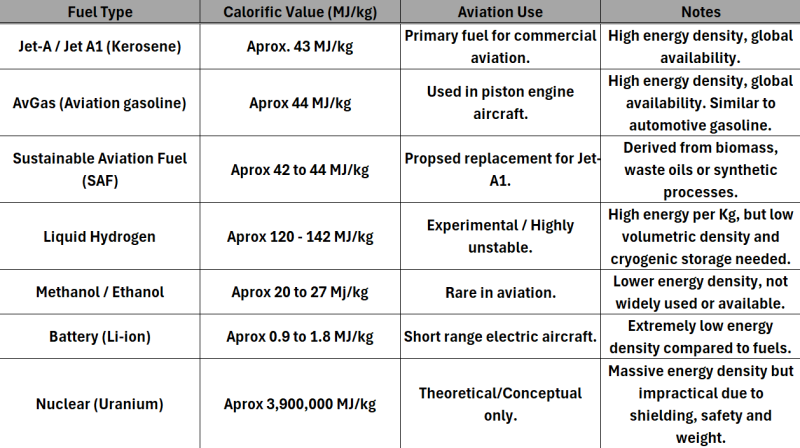

If we have a look at the Calorific Value of existing and potential aviation fuels, it is easy to conclude that, in the near future, nothing can come close to the energy potential of fossil fuels, with the exception of nuclear energy, something that is completely out of the question for now.

Given the example of GlobeAir's and Lillium's failed attempt at integrating traditional and proven charter flight methods with the new and untested eVTOL technology, we need to conclude that, at least initially, flight services offered by these new, all-electric aerial vehicles will be as standalone short hops and in geographies with relatively empty skies and good weather.

Over the past ten months, there have been a number of announcements by companies such as Archer Aviation, eHang, Doroni Aerospace, and ePlane around plans to launch air taxi services in cities in the Middle East. At the same time, and in order to fix the ground infrastructure conundrum, the vertiport company SkyPorts has announced a series of partnerships in the region to begin construction on a number of sites to allow these services to begin as early as 2026, but more likely in 2027.

These deployments will provide the industry with the flight hours and ground experience that will shape the final business model to be used. Everyone entering this industry will be well served by remembering that aviation is a low-margin, high-expense business, and that all of us involved in it are here largely due to our love of airplanes and being around them. The future of this new sector within aviation and the enigma of how it will integrate with traditional aviation forecast exciting times ahead, but entering this arena thinking that there will be huge profits is a mistake.

Comments