In a recent article, I mentioned the almost simultaneous announcements by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) about changes to the regulation of Light Sports Aircraft (LSA) with the publication of MOSAIC, the modernization of special airworthiness certification, and the long-awaited publication of the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) of Part 108 that directly affects uncrewed aviation activities beyond the visual range of the operator (BVLOS).

These are not, however, the only major announcements by the agency that affect how vehicles occupying the National Airspace System (NAS) both interact with each other and eventually will integrate their respective operations.

On August 13, just a few days after the Part 108 NPRM announcement, the new federal administration in Washington announced the “Enabling Competition in the Commercial Space Industry,” which directs the Department of Transportation - and by extension, the FAA - to streamline environmental reviews and licensing procedures for commercial space launches and reentries. It also calls for reevaluation of Part 450 regulations, potentially expanding categorical exclusions under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and easing requirements for hybrid and reusable vehicles.

This means that the already busy federal agency, in the span of one month, revised, updated, and received marching orders that deeply affect crewed and uncrewed aviation as well as commercial space operations. So, how can an agency suffering from tremendous pressure to reduce costs and have a leaner workforce be effective on all fronts, at all times, and with a perfect safety record?

.jpg.small.400x400.jpg)

I’m afraid the answer is not very reassuring.

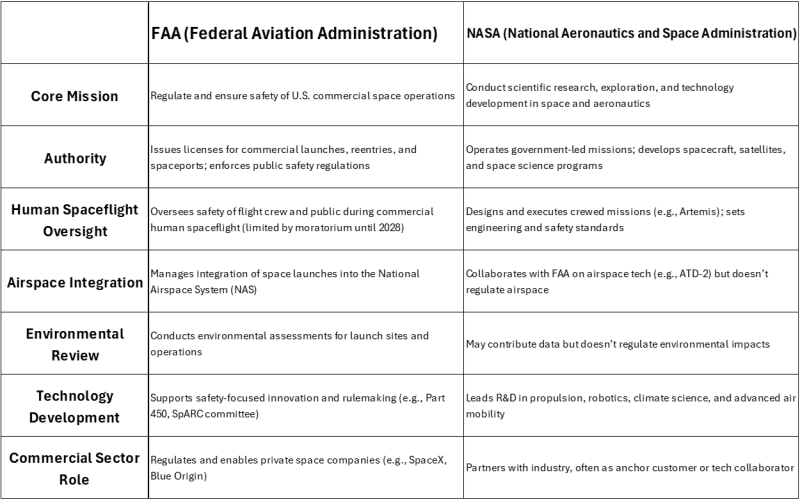

Let’s analyze the FAA’s mandate with respect to space operations, so we can then move on to the potential impact on our industry.

The FAA plays a surprisingly central role in space, especially in the booming world of commercial spaceflight. While NASA gets most of the spotlight for exploration and science, the FAA is the gatekeeper for launches, reentries, and safety when it comes to private space operators.

Here's how the FAA’s role in space breaks down in a nutshell:

- Licensing Launches and Reentries

- The FAA licenses all U.S. commercial space launches and reentries, whether they happen domestically or abroad. This includes missions carrying satellites, cargo, and even humans in cases such as space tourism or crewed flights to the International Space Station (ISS).

- The FAA licenses all U.S. commercial space launches and reentries, whether they happen domestically or abroad. This includes missions carrying satellites, cargo, and even humans in cases such as space tourism or crewed flights to the International Space Station (ISS).

- Protecting Public Safety

- Its primary mandate is to ensure that space operations don’t endanger the public, property, or national security. Operators must prove they can conduct missions safely.

- Its primary mandate is to ensure that space operations don’t endanger the public, property, or national security. Operators must prove they can conduct missions safely.

- Airspace Integration

- The FAA coordinates with air traffic control to safely integrate space launches into the national airspace system. This is critical as launch frequencies continue to increase and spaceports pop up across the U.S.

- The FAA coordinates with air traffic control to safely integrate space launches into the national airspace system. This is critical as launch frequencies continue to increase and spaceports pop up across the U.S.

- Environmental Oversight

- It evaluates the environmental impacts of launch sites and operations, issuing permits and approvals accordingly.

- It evaluates the environmental impacts of launch sites and operations, issuing permits and approvals accordingly.

- Regulatory Development

- The FAA develops rules and standards for commercial spaceflight, including the new Part 450 rule that streamlines licensing for multiple missions. It also collaborates with international partners and industry stakeholders to shape global norms.

- The FAA develops rules and standards for commercial spaceflight, including the new Part 450 rule that streamlines licensing for multiple missions. It also collaborates with international partners and industry stakeholders to shape global norms.

- Human Spaceflight Oversight

- While currently limited by a Congressional moratorium on regulating crew safety, set to expire on January 1, 2028, the FAA still oversees basic safety protocols for flights with humans on board. Once the moratorium lifts, expect more robust health and safety regulations for space tourists and commercial astronauts.

- While currently limited by a Congressional moratorium on regulating crew safety, set to expire on January 1, 2028, the FAA still oversees basic safety protocols for flights with humans on board. Once the moratorium lifts, expect more robust health and safety regulations for space tourists and commercial astronauts.

The FAA’s Office of Commercial Space Transportation has already licensed over 1,000 space operations as of August 2025, a milestone that reflects how fast this sector is growing. It's not just about rockets anymore; it's about building a safe, scalable infrastructure for the next era of space access.

When we think of space, we tend to think of NASA, not the FAA, so where are the delineations separating the two important federal agencies?

Clearly, the FAA is a regulator. Its job is to ensure that private space operations don’t harm the public or disrupt national airspace. It’s reactive and compliance-driven. On the other hand, NASA is a research and mission agency. It pushes boundaries in science and exploration, often leading the way in technology that later gets adopted by industry. They do collaborate, especially on emerging areas like Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) and human spaceflight safety standards, but their mandates remain distinct.

All of this means that the FAA staff are being asked to master three radically different regulatory domains, each with its own unique needs. Errors in one domain (e.g., misjudging a BVLOS corridor or launch trajectory) could have cross-domain safety consequences. In simpler terms, this means accidents, in a time when layoffs are happening across the federal government, including within the FAA itself. This, I’m afraid, creates a chilling effect: fewer staff, higher expectations, and reduced institutional memory, especially dangerous in safety-critical roles.

The FAA is expected to accelerate licensing, especially for space and drones, while maintaining a sterling safety record, and this will only lead to risky regulatory capture, rushed approvals, or overreliance on industry self-certification. Let’s keep in mind that this is not necessarily a cohesive team making every decision; each mandate has its own rulemaking team, advisory committees, and tech stack. Without strong inter-office coordination, policy silos could emerge.

One recent example is that MOSAIC’s experimental aircraft rules now intersect with space support vehicles, but are managed separately from the Office of Commercial Space Transportation.

So, the question for our industry, especially commercial drone and potentially air taxi operators, is, what potential areas of conflict exist, and who will oversee what?

The three mandates (MOSAIC, the commercial space mandate, and Part 108) are not just parallel reforms; they’re intersecting tectonic plates in the FAA’s regulatory landscape. Each one reshapes how aircraft, drones, and space vehicles operate, but they weren’t designed to harmonize. In other words, without unified airspace management, drones, “chase” planes, and launch vehicles could compete for the same airspace, especially near spaceports or during mission windows.

Regarding who oversees what, MOSAIC is managed by the Aircraft Certification Service (AIR), focusing on airworthiness and pilot privileges, while Part 108 is being developed by the UAS Integration Office, with new standards for detect-and-avoid, remote pilot training, Meanwhile, autonomous and space operations fall under the Office of Commercial Space Transportation (AST), which licenses launches and reentries but doesn’t certify aircraft.

We can foresee a future in which a single operator might need approval from all three offices. For instance, a drone used to monitor a launch, or an experimental aircraft supporting a space mission, may face duplicative or conflicting requirements.

Each of the three mandates has its own safety protocols, risk models, and enforcement mechanisms. While MOSAIC allows more flexible operations for experimental aircraft, it may not align with public safety protocols for launch support, while Part 108 introduces autonomous drone fleets that could operate near launch zones or experimental aircraft without clear coordination. In the case of conflict, it’s unclear at this point which office leads the investigation or is in charge of enforcement.

The FAA is being pulled in opposite directions, toward deregulation for innovation, and toward stricter oversight for safety and equity, and at the same time, it is not receiving the right tools and personnel to do it properly. All these urgent mandates are creating a regulatory maze without providing adequate time to create cross-office coordination protocols, unified airspace and safety frameworks, and integrated digital systems for licensing and certification.

As a professional in both crewed and uncrewed aviation, I do not envy the folks at the FAA trying to make all this work. Satisfying the demands for dominance in all these fields, while cutting personnel and requiring new and more modern regulations in a hurry, will not be easy. I hope, for the sake of our industry, the commercial space operators, the LSA community, and the flying public (myself included), that it all works out at the end. But hope is not a plan, and it will never be.

Comments