In a few days the U.S. federal government shutdown will be entering its second month, presenting implications for a large number of people and industries. In the specific case of the uncrewed aviation industry, the comment period for the Part 108 Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) closed on October 6, exactly six days after the beginning of aforementioned administration closure. At this point we have no idea if these comments have been analyzed or even received.

The fact is that air traffic controllers (ATC) are still working, but just recently missed their first paychecks. It is safe to assume that non-essential personnel, such as those working on the Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) ruling, are also not getting paid, and many are currently furloughed and not workng at all.

The industry was hopeful that a final ruling would be possible by early 2026, but now the deadline previously imposed by the White House seems to be in peril.

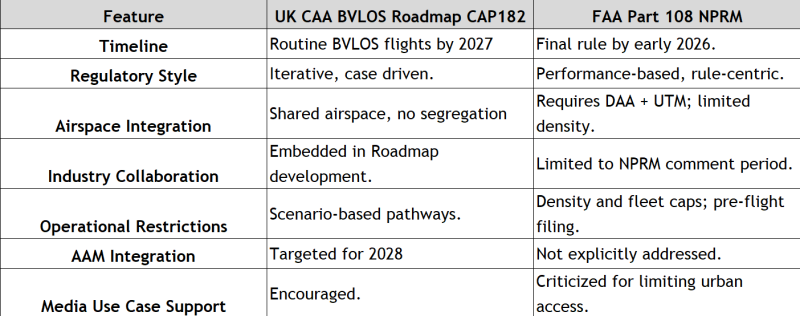

As this has been happening, the UK recently announced their own BVLOS proposal that clearly distinguishes itself from the NPRM in the U.S. It is clear that regulators on both sides of the Atlantic are racing to define the rules for BVLOS operations. While both aim to normalize scalable BVLOS operations, their philosophies, timelines, and constraints reveal divergent paths toward integration, and that is worth of a more in-depth analysis.

The U.K.’s Iterative Vision: CAP3182

The U.K. Civial Aviation Authority's (CAA) roadmap, published as CAP3182, outlines a progressive strategy to enable routine BVLOS operations by 2027. Rather than imposing a rigid rule set, the CAA proposes a phased integration model aligned with the U.K.’s Airspace Modernization Strategy (AMS). The roadmap is built around three operational pathways:

- Atypical Air Environments (AAE): BVLOS flights in areas with low aviation activity, such as rail corridors or offshore wind farms.

- Low-Level Urban BVLOS: Operations under 500 feet AGL in populated areas, with enhanced safety protocols.

- Fully Integrated BVLOS: Shared airspace operations alongside crewed aircraft, requiring advanced detect-and-avoid capabilities.

The roadmap is supported by 14 industry-led projects, each contributing to the development of standards, technologies, and safety cases. The CAA emphasizes real-world trials, iterative capability delivery, and collaborative governance. Notably, the roadmap avoids segregated airspace, aiming instead for seamless integration.

What the proposed ruling ignores completely is the recent administration of Altitude Angel, the uncrewed traffic management (UTM) cornerstone of the UK’s BVLOS strategy. In terms of delaying, in our opinion this technology ‘absence’ will have the same effect in the U.K. as the government shutdown is having here in the U.S.

The FAA’s Rule-Based Approach: Part 108 NPRM

In contrast, the FAA’s proposed Part 108 rule seeks to codify BVLOS operations through a performance-based regulatory framework. Published in response to Executive Order 14307, which mandates final rule issuance by early 2026, the NPRM covers:

- Aircraft design and airworthiness

- Detect-and-avoid (DAA) performance

- UTM integration and pre-flight plan submission

- Third-party service provider roles

The rule is designed to support commercial BVLOS use cases such as delivery, agriculture, and infrastructure inspection. However, it introduces several constraints that have drawn industry criticism, from both the traditional crewed aviation membership organizations, such as AOPA and NBAA, and uncrewed aviation leaders. Both groups have expressed deep disagreements with the federal agency, specifically:

- Population Density Limits: BVLOS flights are restricted to Category 3 or lower, excluding dense urban areas and limiting media operations.

- Fleet Size Cap: Operators are limited to 24 active BVLOS drones, raising concerns for scalability.

- Pre-Flight Plan Requirement: Each BVLOS sortie must be pre-approved via FAA submission, which may hinder dynamic missions like journalism or emergency response.

As mentioned, the NPRM’s comment period closed on October 6, with stakeholders urging revisions to better accommodate real-time and high-density operations and traditional aviation trying to prevent further incursions of drone operations near airports.

Comparative Analysis

The FAA’s population density restrictions and fleet caps represent significant barriers for operators in urban environments. News organizations, for example, may struggle to deploy BVLOS drones for live coverage in cities. The U.K.’s roadmap, by contrast, offers more flexibility through scenario-based integration and does not impose fleet limits.

It is clear in both proposed regulations that there is a preference for a gradual deployment in rural areas and then, as we gain experience and the realities of BVLOS sink in, the operators will be allowed closer to urban centers.

The U.K. explicitly links its BVLOS roadmap to AAM readiness by 2028, ensuring that drone integration aligns with broader airspace transformation. The FAA’s NPRM does not yet address AAM, though future rulemaking may expand its scope. It is understood by industry experts that passenger flights in the new modality of eVTOLs will be initially piloted by a single pilot monitoring an autonomous flight. A completely pilotless aircraft is nowhere in the near future in either proposed regulation.

The FAA’s accelerated timeline—driven by executive mandate—offers regulatory certainty but risks rigidity. The UK’s slower, more collaborative approach may yield greater adaptability, especially as technologies and use cases evolve.

Even though each approach seems to be different, both civil aviation authorities are struggling to come up with a workable solution to add thousands of non-piloted aircraft to their extremely busy airspaces, and what they have in common is delays and more delays until they find a workaround that is safe and viable.

The U.K.’s roadmap reflects deep industry involvement, with projects co-developed by regulators and operators. The FAA’s NPRM, while open to public comment, has faced criticism for limited responsiveness to stakeholder concerns, particularly around operational constraints. Both frameworks face implementation hurdles. In the U.S., the government shutdown has delayed waiver processing and may impact rule finalization. In the U.K., the success of the roadmap depends on sustained industry collaboration and timely delivery of enabling technologies and, most importantly, finding a suitable, new UTM technology.

The loss of Altitude Angel leaves a vacuum in digital coordination, especially for BVLOS flights in shared airspace. The CAA must now identify alternative UTM providers or develop a multi-vendor strategy to maintain roadmap momentum. Operators are being urged to review dependencies and seek replacements, but interoperability and safety validation remain challenging. Experts warn that Europe’s reliance on a few UTM providers weakens resilience, especially amid growing geopolitical tensions.

A rather nasty implication of all this is that harmonization across jurisdictions remains a challenge. As global drone operators seek cross-border scalability, differences in detect-and-avoid (DAA) standards, UTM protocols, and operational limits could complicate deployment. What ICAO has done in the homologation of international procedures for crewed aviation so effectively, must now act as the perfect roadmap to follow and do the same in uncrewed aviation.

The U.K. and U.S. are charting distinct courses toward BVLOS integration. The U.K. CAA’s roadmap prioritizes flexibility, collaboration, and phased capability delivery while the FAA’s Part 108 NPRM emphasizes rule-based scalability but imposes constraints that may limit innovation in dense environments.

For stakeholders, understanding these differences is critical. Whether you’re a drone manufacturer, operator, or policymaker, aligning your strategy with the evolving regulatory landscape will be key to unlocking the full potential of BVLOS operations. These delays on both sides of the Atlantic are giving the industry time to think for better ways to integrate and help the civil aviation authorities to give these last steps towards full integration of crewed and uncrewed aviation.

Comments